Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

Playback is the third Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial, an exhibition which replaced the Dobell Drawing Prize (held 1993-2012 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales) during its recent hiatus. In contrast to single works by dozens of finalists in the prize exhibitions, the curated Biennial, also at AGNSW, offers more ambitious contributions by a smaller selection of artists.

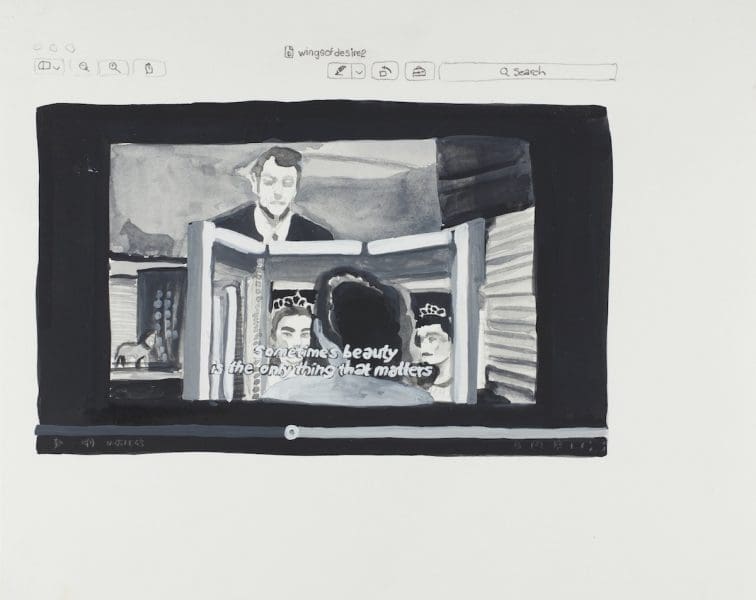

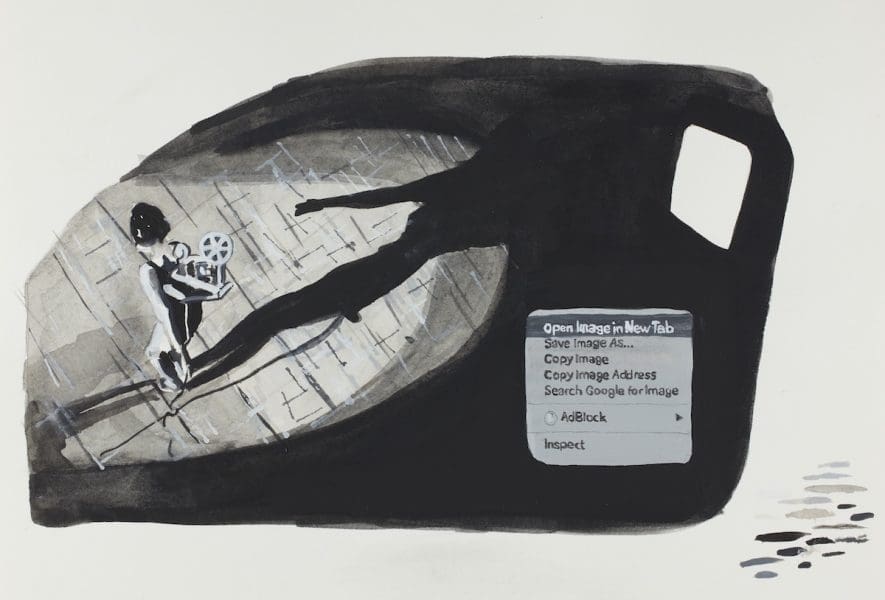

Curatorially, this year’s Biennial highlights the links between drawing and other disciplines, in particular film. The wall text outlining these links reads as an attempt to prove the relevance of drawing in a contemporary context – as if anyone was arguing. For the eight selected contemporary artists, drawing either underpins an interdisciplinary practice, or stands alone as a powerful and direct tool for storytelling. Drawing traditionally takes the form of charcoal on canvas or graphite on paper, but arguably one can draw with anything that makes a mark: sand, light, ink, paint.

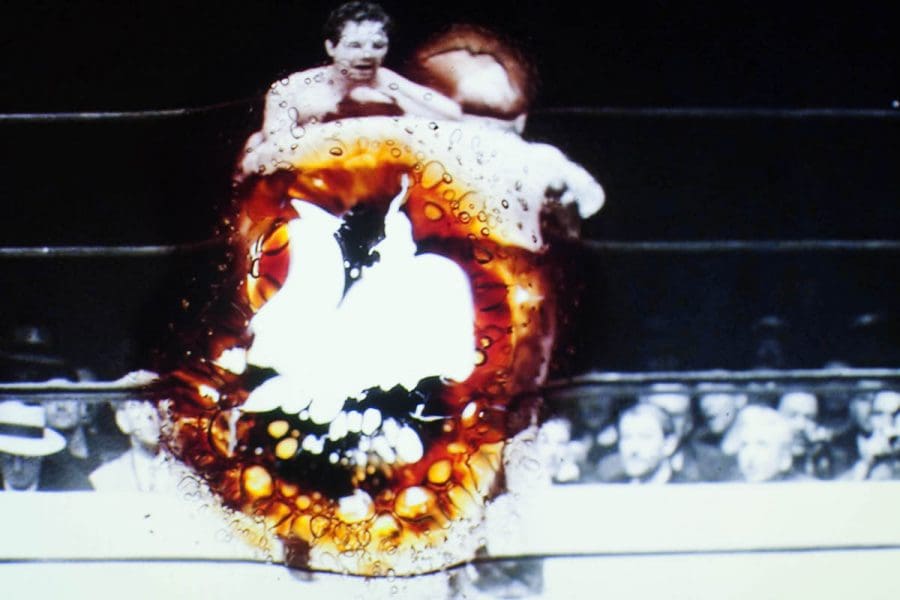

A highlight of the exhibition, and perhaps the most unusual interpretation of drawing, is Nick Strike’s Box of clouds, 2017. Strike focused light through a magnifying glass to burn out the figures of two boxers, frame by frame, on an old 16mm film. In the resulting moving image, the fighters are blister-edged absences chasing each another around the ring. The referee appears to corral blobs that continually separate and coalesce, like cells splitting and re-forming. Usually light is used to expose an image on film, but here it is focused into a point through a hand-held glass, becoming a tool for drawing and erasure.

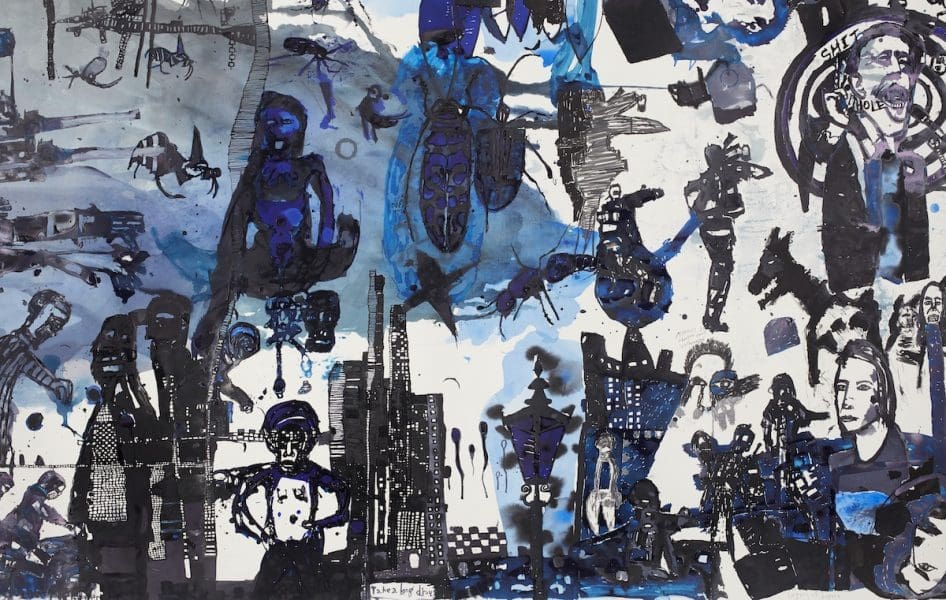

Also stretching the definition of drawing are works by Dorota Mytych and Jason Phu. Mytych creates shifting images in sand – a human figure becomes a horizon line, a dog shape-shifts into a nebula – and presents these transformations as grainy black-and-white films. Phu films a performance of a drawing and presents the props and documentation of that action. The ‘drawing’ itself, made with paint on a black plastic drop sheet, illustrates a clash of cultures; incidental Pollock-esque drips of paint render Chinese pictograms almost illegible. Phu’s and Mytych’s works, as well as Strike’s, expand the traditional definition of drawing as pencil or charcoal on a two-dimensional surface.

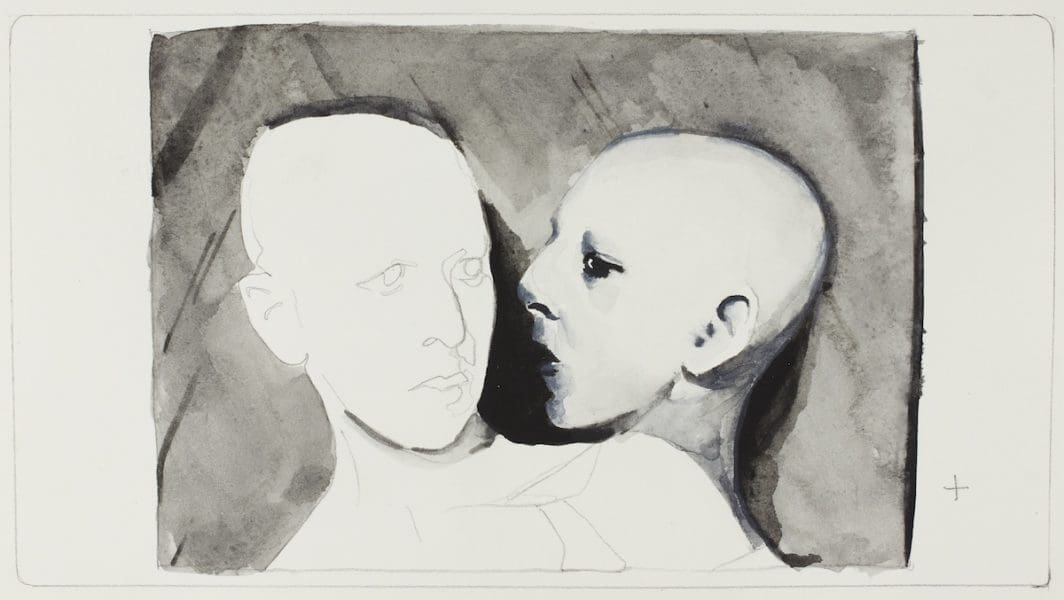

More traditional approaches to drawing are used to powerful effect by Vernon Ah Kee and Lucienne Rickard. Ah Kee constructs a ghostly, dematerialised face through a build up of faint, spidery charcoal lines. Text panels on either side detail Indigenous experiences of discrimination and subjugation. Rickard’s larger-than-life human and animal figures are glistening and alive, dense with directional marks in dark, glossy graphite on milky drafting paper.

Sharon Goodwin’s writhing animal figures would have been richer as freestanding sculpture; her most interesting work is presented this way elsewhere. Phu’s installation, presented along a wall, would usually expand on to the floor space of a gallery. Playback is surrounded by another AGNSW exhibition in which installation works take up space; perhaps a wall-bound presentation was a necessary point of difference. But the exhibition suffers from this constraint.

It has just been announced that the Dobell Prize for Drawing will relaunch in 2019, at the National Art School Gallery, and run in alternate years to the Biennial. It seems that drawing, with its expanding boundaries that accommodate shifts in contemporary practice, continues to be relevant – even popular. It makes sense: drawing is relatable. It is something we all do, or at least did before learning to write. It is a universal language, and a powerful way in to understanding and connecting with contemporary artistic practice.

Playback: Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial 2018

Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW)

7 July – 21 October