Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Philippe Parreno, C.H.Z., 2011, runtime: 12 minutes 49 seconds, color, sound mix: 5.1, aspect ratio: 1.77, © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Gallery Esther Schippe.

Philippe Parreno, C.H.Z., 2011, runtime: 12 minutes 49 seconds, color, sound mix: 5.1, aspect ratio: 1.77, © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Gallery Esther Schippe.

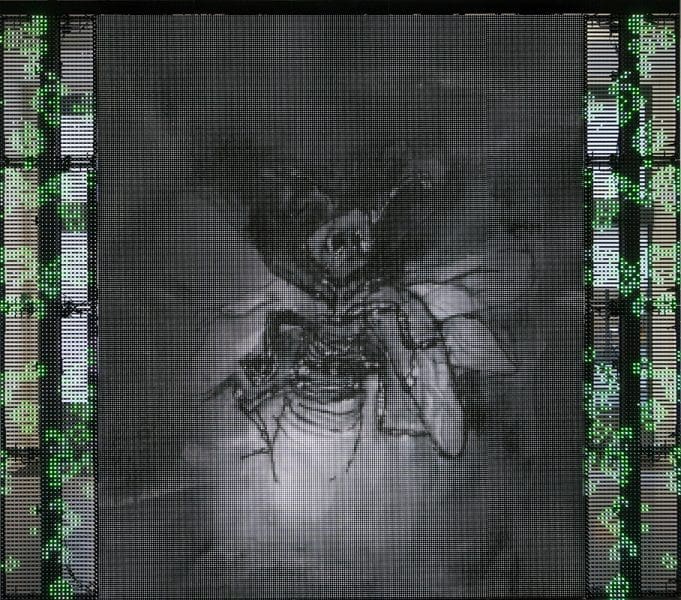

Philippe Parreno, With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life (Green, Rule#1), 2014, installation, 8 LED panels MARTIN PRO EC-20,10 LED panels MARTIN PR0 EC-10, Mac mini, speakers, amplifiers, light captors, © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Pilar Corrias.

Philippe Parreno, With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life (Green, Rule#1), 2014, installation, 8 LED panels MARTIN PRO EC-20,10 LED panels MARTIN PR0 EC-10, Mac mini, speakers, amplifiers, light captors, © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Pilar Corrias.

Philippe Parreno, Li Yan, 2016, digital film with 5.1 sound, 16 minutes 18 seconds, © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Gladstone Gallery and Anna Lena Films.

Philippe Parreno, Li Yan, 2016, digital film with 5.1 sound, 16 minutes 18 seconds, © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Gladstone Gallery and Anna Lena Films.

Philippe Parreno, The Boy from Mars, 2003, 35 mm, transferred to HDCAM color, Dolby SR sound, runtime: 10 minutes, 39 seconds, © Philippe Parreno.

Philippe Parreno, The Boy from Mars, 2003, 35 mm, transferred to HDCAM color, Dolby SR sound, runtime: 10 minutes, 39 seconds, © Philippe Parreno.

Philippe Parreno, Marilyn, 2012 , runtime: 19 minutes 49 seconds, color , sound mix: 5.1 , aspect ratio : 2.39 , © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Pilar Corrias Gallery.

When French artist Philippe Parreno visited in November to set up an exhibition at Melbourne’s ACMI, it was an experiment in the art of the exhibition. For him, the show is itself art-in-progress, not merely a vehicle to display discrete works.

ACMI curator Emma McRae hesitates to describe what we might see. She interprets his process-oriented approach as a sort of choreography – one in which his various single-channel films, for example, may or may not make it onto the play list. “In general what he is interested in doing is presenting a kind of retrospective of his films,” she says. “Yet saying this conjures a very different idea of what he will probably be doing.”

Building a pseudo cinema environment in the largest ACMI gallery, Parreno will not have a chronological screening of films such as Marilyn, C.H.Z. (Continuously Habitable Zones) or Invisibleboy in the show Thenabouts, opening December 6. Rather, he will develop computer algorithms that will randomise what happens on-screen.

“What he wants to do at ACMI is for that process to be run by a human being,” McRae says. “So there will be a person in the gallery space who is essentially programming the exhibition, kind of like a host. Because a lot of the films have different aspect ratios, this person will have to physically go and change the width of the screen.” They will do so by pulling a rope to adjust the curtains – very old-fashioned and theatrical.

Likewise, there will be a Yamaha disklavier piano – like an old pianola, it plays itself. Unsurprisingly, with that spectral music serenading the audience, much of Parreno’s work references ghosts and absences, the present and past. “And so it is old, but new,” McRae says.

Philippe Parreno

Australian Centre for the Moving Image

6 December – 13 March 2017