Phaptawan Suwannakudt brings Thailand’s Wat Pho temple to Australia through her multi-sensory installation Knowledge in your hands, eyes and mind at the Arts Centre Melbourne as part of Asia TOPA: Asia-Pacific Triennial of Performing Arts. Originally working as a temple muralist in Thailand, Suwannakudt moved to Sydney in 1996. The artist now focuses on remembering and sharing personal and collective histories through painting, sculpture and installation. Michaela Bear spoke to Suwannakudt about life growing up in a temple, gender inequality in Thailand, and her continued connection to cultural space through her artistic practice.

Michaela Bear: Your father was an esteemed artist. How did he influence your creative development?

Phaptawan Suwannakudt: The development of my artistic practice is complex. My father was not a conventional mural painter for a Buddhist temple. He studied sculpture and painting under an Italian professor. At six, my father’s father passed away, so he grew up living between two uncles. He left for Bangkok once an adult, living homeless in a temple during his art studies. In this new city he gained a reputation in painting, poetry, critical writing, philosophy and developing modern dance performances. These experiences led to commissions for large-scale murals in theatres, cinemas and hotel lounges.

My father later went on to stay in a temple while training a group of young people to paint his first and only temple mural, which was still incomplete when he passed away. I spent my childhood in this temple. As a child I was allowed to live inside, despite it being against the rules for women to stay. Apart from giving me access to tools and equipment, I was never given instruction to draw or paint from my father. But I followed him everywhere, including weekly meditation sessions with a venerable monk.

My father exposed me to books and poetry. He encouraged me to write, sent me to read English and German at the University and later organised his friend and renowned poet and painter Chang Sae Tang to mentor me. This was two years before he passed away in 1982. Chang Sae Tang passed away not long after.

I was 22 and left to lead the muralists to complete my father’s project. It was only then that I made the decision to become a mural painter.

I spent these first few years making art full-time during the day with scarce income and doing translation for magazines at night to earn extra money to look after my mother and younger siblings.

MB: Your installation at the Arts Centre Melbourne was previously exhibited at Wat Pho temple as part of the Bangkok Art Biennale in 2018. How did these two cultural sites shape the work?

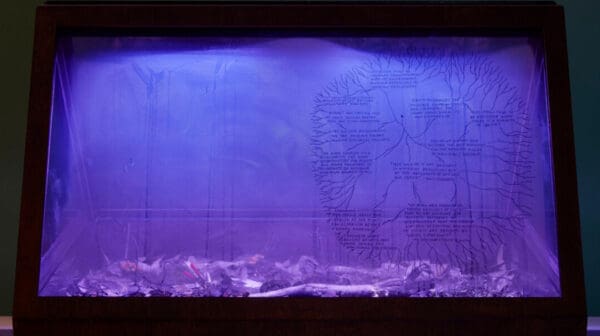

PS: I was 10 when my father took me along with him to a dance workshop he was running at a studio near Wat Pho. We often went to the temple to see the internal mural, which depicted scenes from Ramayana, Chinese artefacts and sculptures. Apinan Poshyananda, the artistic director of the Bangkok Art Biennale approached me to do a project at Wat Pho. Drawing on childhood memories, the final site-specific installation included a mural painting depicting the history of the temple, appropriating elements of its existing features to form a new composition. Copied from the temple walls, a group of drawings on Perspex panels present Thai script of the 32 ethnicities residing in Bangkok when the original carvings were created.

Wat Pho is also registered with UNESCO as a “Memory of the World” based on the knowledge the temple provided to the public. The inscribed wall text and diagrams for traditional massage have been passed on through generations. Based on the temple’s epigraphic archive, my work incorporates suspended figures, recorded recitations from the Thai Buddharangsee Community Language School in Sydney, and remedial herbs used in massage.

The installation highlights Wat Pho as a place of knowledge and wisdom offered to everyone.

For the Arts Centre, the two-sided mirror panels are restructured to reflect the movement of audience members when entering and exiting the corridor, causing them to momentarily become part of the work – the past and present briefly converging. I also created a dome centrepiece with a reflective base, referencing the Arts Centre when it used to be a circus.

MB: What is most important when developing site-specific work?

PS: Respect is key. Spaces are full of memories and accumulated energy, moving and evolving through time.

MB: In 1995 you were one of the founders of Womanifesto, a biennial project showcasing the work of female artists internationally. Is feminism part of your individual practice?

PS: While I had a feminist father, I grew up in an environment where women missed out on basic things that men took for granted. For example, women in Thailand cannot get ordained to be a monk. Unfortunately it is believed that women are born with less Karma. To subtly counter these prejudices I always included equal numbers of men and women in my painting team. I was among the first women to paint in a Buddhist temple.

A girl I know was sold by her parents to a brothel in front of the temple where I created my first mural. I was shocked to learn that many families in that area sold their daughters to earn money. A local female politician initiated a vocational centre where women could be independent and break free of this vicious cycle. My 1996 Nariphon series portrayed a girl as a regenerating fruit, metaphoric of the outdated beliefs and expectations of women that have taken root and continue to be passed down through generations.

MB: In a previous interview you mentioned that art is a tool to communicate and challenge. How do you hope to challenge audiences with your work?

PS: I am not sure when I started using the word ‘why’ as a point of departure to start a work rather than ‘how.’ The ‘why’ generates tension and conversation, rather than an answer. In the process of making I engage with the world around me. Once a work is complete I hope to bring visitors into this conversation too.

Knowledge in your hands, eyes and mind

Phaptawan Suwwannakudt

Arts Centre Melbourne

8 February – 22 March