Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

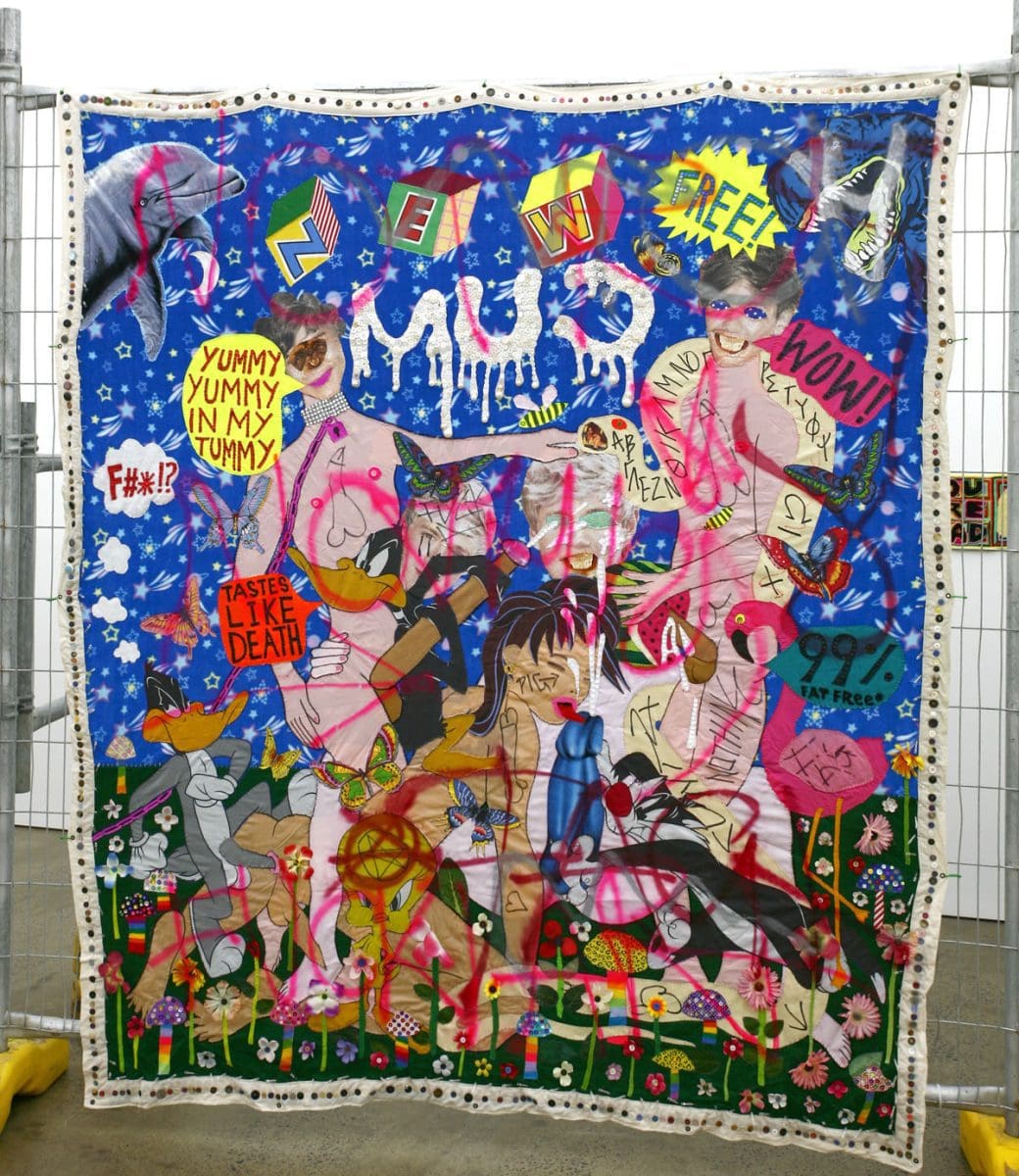

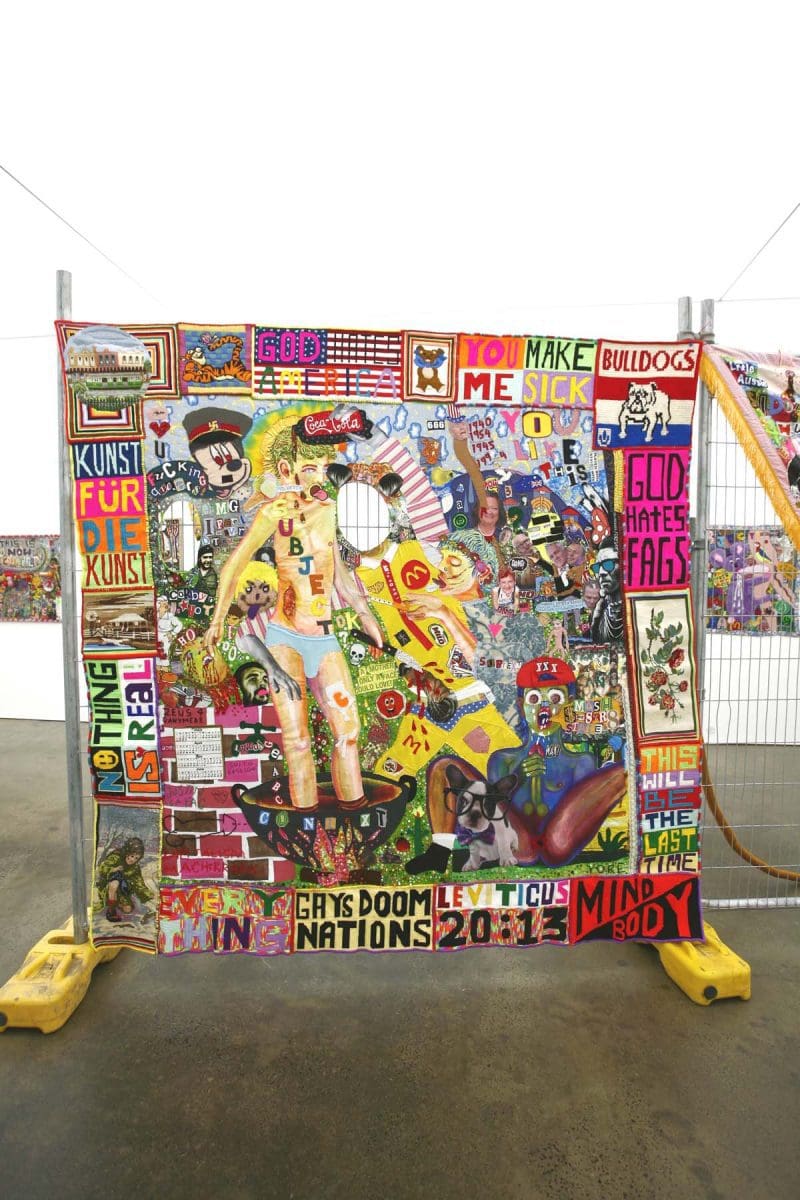

For Paul Yore’s latest solo exhibition at Neon Parc, Your Capital is at Risk, the artist has mined his own practice in the same way he mines popular culture: pulling together every possible scrap of material into a jangling visual cacophony. Alongside two-dimensional textiles and a suite of new large soft-sculptural works, Yore has peeled back his process by exhibiting a selection of drawings and collages produced over the past 12 years. Anna Dunnill visited the gallery and spoke with the Victoria–based artist about deconstructing culture, the physical extremes of craft, and its radical potential.

Anna Dunnill: Let’s start by talking about these soft sculptures.

Paul Yore: These are all brand new works for the show. They come out of wanting to utilise materials from the last five to eight years of working with textiles, that I haven’t been able to utilise in the 2D works. So they were born out of necessity! They’re all made from off-cuts. And they’re even stuffed with other materials, off-cuts and things, as well.

And I’m always trying to cannibalise my work into itself and to push that to its logical conclusion! These forms were a particularly rich site for that type of process.

I’ve been working with the flat 2D works for a few years and I feel like it has almost exhausted itself, because I’ve pushed the pictorial language so far. Like, there’s only so far that I can go before I’d have to use some other kind of medium to build on this visuality – computer animation or something. I’m always trying to push through that threshold where the content is exhausted to the point that the work almost empties out from itself; there’s no static point for the eye to anchor itself, and the work becomes this surface that the eye sort of swims through. That’s the kind of conceptual space that I want the work to be vibrating on.

AD: A lot of these subjects you’re talking about and pulling apart are really toxic aspects of our culture. With the craft works, in particular, how does it feel to spend hours at a time intricately stitching and beading those things?

PY: It’s necessary, I would say.

I have long struggled with the question of art’s function in society and the utility of art. It’s an unresolvable question. For me, personally, it’s a survival mechanism. If I wasn’t doing this, I don’t know what I would do. I often joke to people that if I wasn’t an artist I’d be a serial killer. (Just a joke!) But I’m trying to talk to the amount of energy that’s involved in the transference of something – and how necessary that is.

There are all these unhealthy modes of expression in our society. In Australia it’s mainly drinking culture, which is attached to violence. Basically if more men took to sewing and knitting we’d live in a less messed up society! So for me it’s a totally necessary thing. And the labour that’s involved with it is also therapeutic and cathartic, because I push production to such extremes. It’s actually really testing me physically. I have suffered from RSI.

AD: Yes, I was going to ask about that.

PY: It’s such a real thing.

AD: Do you do all the labour yourself, or do you work with a studio assistant?

PY: My partner does sew with me as well. We will sit and watch the football and be sewing sequins on the work. Everything is hand-stitched. I’ve recently been trying to work in a bit of machine sewing where I can, but the nature of a lot of the intricate work is that you can’t machine sew it, it has to be hand sewn.

When I first started out, I was working in needlepoint, where the whole image is built up from individual stitches – which is a ludicrous way to make something unless, you know, it’s in the traditional medieval tapestry workshops where there were guilds of 20, 30, 40 people working on something this size.

After I started working in that medium, because I constantly want to make things larger for some reason, I started working in appliqué: cutting things out and stitching them together. That has allowed me to work on this scale. They still take months and months to make, but if I was using the needlepoint method on this scale they’d easily take 10 years.

AD: How long do they actually take?

PY: It’s hard for me to quantify it, because I do work across a few at a time and I’ll go back to things.

AD:Tell me how your collages and drawings inform that process.

PY:Well, the drawings sort of sit underneath all the other work, almost like a blueprint. They are obviously more immediate, and most of them I never made as finished works. There’s a vulnerability in even showing them, because they are things I never thought anyone was going to look at! But at some point I decided that it was a valid body of work that I could excavate.

Some of them are studies for other works, but largely they’re just an uninhibited space of automatism. I like that about drawing, it sort of just comes out as you’re doing it. It’s not really planned or premeditated in any way.

And the collages relate really strongly to the textiles, because it’s the same methodological principle. I’m very interested in this generative conflict between collage, that centres on cutting things up and deconstructing them, and sewing, which centres on repairing, on putting things back together. So it’s this constant state of cutting things up and then putting them back together. And it’s in that space in between them that new meanings are created, that the work opens up in some sense.

AD: How did you get into needlepoint initially?

PY: It kind of happened accidentally. It was about eight or nine years ago, and I was having some mental health issues. I started doing it really randomly, not even thinking about its viability as an art material or anything – I just started doing it and became really addicted.

I’ve always had this sense that it’s therapeutic, because it was a small crisis in my life when I did start doing it. It’s always had that kind of redemptive thing about it. It’s very repetitive and meditative.

It’s nice to do something that’s not at that pace, like gardening or meditation or something. It has that same principle to it; it requires discipline, but it has a simplicity, it has a rhythm, and it’s based on a time scale where you have to defer your need for instant gratification.

That’s what I love about it. And in that sense I see it as countercultural, actually. It’s not a coincidence that sewing has been used in feminist art, in queer art, and in other art from minority communities, because I think it does directly oppose the principles and values of mass consumer culture in an industrial-techno society. I think embracing these slow processes – it’s radical.

Your Capital is at Risk

Paul Yore

Neon Parc – Brunswick

27 October – 15 December