Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Paul Ryan, Still Life with Red Flowers, 2019, oil on linen, 122 x 122cm.

Paul Ryan, Banks and Wattle, 2019, oil on linen, 210 x 190cm.

Paul Ryan, Banks and Florilegium, 2019, oil on linen, 138 x 122cm.

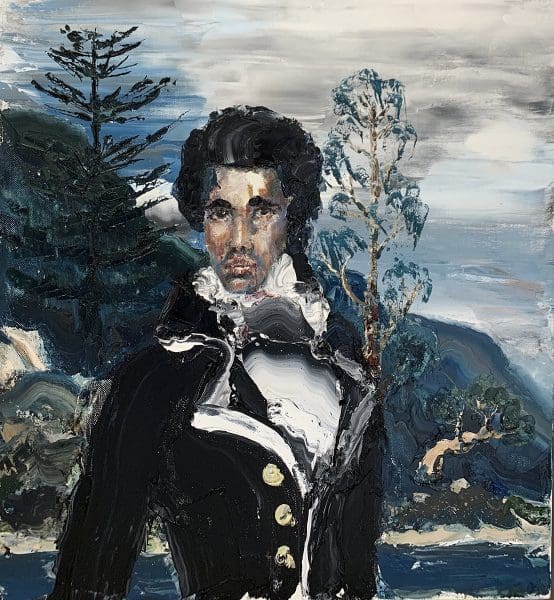

Paul Ryan, Joseph Banks and Coal Cost Portrait, 2020, 122 x 112cm.

Paul Ryan, Ghost Tress, 2019, oil on linen, 138 x 122cm.

Paul Ryan, Wattle and Yellow Vase, 2019, oil on linen, 138 x 122cm.

The British botanist Joseph Banks is posed by the Illawarra escarpment. Conspicuously foppish, like a post-French revolution notion of the dandy, his hair is coiffed and his dashing trench coat long and cinched. His pantaloons vary from white to pink to blue. In these paintings, on show in the exhibition South Pacific by New Zealand-born artist Paul Ryan, Banks cuts an oddly romantic figure. He is painted in the late afternoon under moody dark clouds in a landscape better suited to board shorts and thongs.

Ryan, whose studio is in Thirroul, NSW, often paints about colonisation and is particularly fascinated by the “juxtaposition between this fine-dressed, handsome gentleman, standing in the wild Australian bush and looking completely out of place.”

Born in 1743, in Westminster, England, Banks joined James Cook’s South Seas expedition. They set out in 1768 to Rio de Janeiro, Tierra del Fuego, Tahiti and New Zealand, before sailing on to Australia in 1770, where Banks gathered plants, birds, reptiles, fish, molluscs and insects.

Banks also noted Aboriginal customs. One of Ryan’s works, A Very Aussie Still Life, 2019, shows two skulls on a table next to a vase, a Union Jack and the Olympic rings. The still lifes in the show are, Ryan says, a “mash up of Pablo Picasso meets Margaret Preston.” Is this work also a reference to genocide?

“I like to put things in a painting that don’t specifically reference anything that has happened, but to leave the viewer with a stark questioning,” Ryan replies. “That is a potential question.” Ryan says that Banks was “for his time, very enlightened because he was one of the early people to start putting together a list of Aboriginal words and language.”

Ryan was born in Auckland and came to Australia aged eight, in 1973, when his professor father took up a position in the University of Wollongong economics department. Several fellow students at his Catholic boys’ high school lived around the Thirroul area, so he would catch the train most weekends to go surfing with them there.

Ryan’s paintings depicting Banks show the Illawarra escarpment in the late afternoon, when more shadows hit the landscape and the clouds are greyer. In some images there are Norfolk pines – a colonist’s imposition on the landscape, being native to an island well north of here.

“When D.H. Lawrence lived here, and he wrote [the novel] Kangaroo, he described the landscape very beautifully. He talked about the ominous presence, and his name for the escarpment was ‘the dark tor’,” says Ryan.

“So Lawrence saw a dark presence there, and there’s a sense that terrible things have happened here in the past. The Indigenous inhabitants of this area were murdered or chased out. There are some very good local historians that have written about local Indigenous people but there’s this great void of information about those who lived north of Thirroul and south of Stanwell Park, pre-settlement,” Ryan explains. “There’s a sadness in a way, because there’s a sense that so much has been lost.”

Ryan has painted enplein air in the past. But most of his work is done in his studio, relying on memories of being in the landscape almost every morning “surfing and soaking it in.”

Paul Ryan: South Pacific

Nanda\Hobbs

6 – 22 February