Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

Noŋgirrŋa Marawili. Photograph: Nat Rogers.

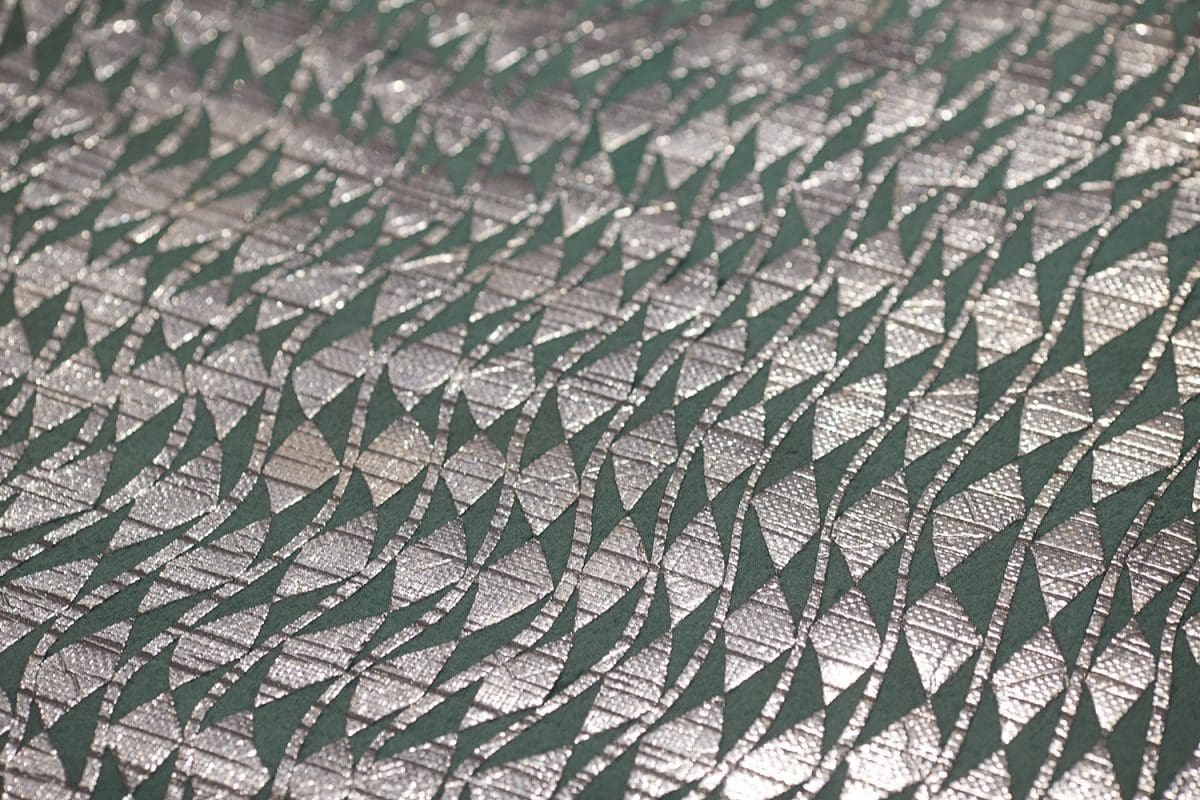

Gunybi Ganambarr, Yolngu people, Northern Territory, born 1973, Yirrkala, north east Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Buyku, 2018, north east Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, insulation; Courtesy the artist and Buku‑Larrnggay Mulka Centre, photo: Rhett Hammerton.

Nonggirrnga Marawili, born c. 1938, Yolngu people, Northern Territory, Baratjala, 2019, earth pigments on stringybark.

Noŋgirrŋa Marawili. Photograph: Nat Rogers.

Gunybi Ganambarr, Yolngu people, Northern Territory, born 1973, Yirrkala, north east Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Wuḏuku, 2018, north east Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, earth pigments on driftwood; Courtesy the artist and Buku‑Larrnggay Mulka Centre, photo: Nat Rogers.

Gunybi Ganambarr. Photograph: Nat Rogers.

Wukun Wanambi. Photograph: Nat Rogers.

Rolling out across Adelaide in October, Tarnanthi, an annual platform for contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, features an art fair, exhibition and festival this year. Pronounced tar-nan-dee, Tarnanthi means to appear or to arise, like the morning sun, in the language of the Kaurna people whose traditional lands take in Adelaide and the surrounding Adelaide Plains. In this iteration of the festival, artistic director Nici Cumpston has focused the spotlight on Arnhem Land, paying respect to systems central to Yolŋu culture.

In the book Welcome to My Country (2013), Laklak Burarrwanga and her family explore the idea of gurruṯu, a complex philosophy at the core of Yolŋu culture in Arnhem Land. Burarrwanga is an Elder of the Datiwuy people and a caretaker for the Gumatj. She has a profound knowledge of Yolŋu views of the world and describes “an infinite pattern” within gurruṯu. “It goes on forever backwards and forever forwards,” she writes.

Gurruṯu encompasses a complex pattern of kinship – who is related to what, who and how. It is a nuanced and interlocking system connecting people with plants, rocks and animals, spirits and celestial bodies, languages and land. Burarrwanga tells us it provides meaning, a place in the world, and is a web of life going from person to person, to land, trees, water, wind, clouds and rivers. In Yolŋu artmaking, it has a special place where this kinship can be explored visually, without the constraints of written or spoken language.

Walk into the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Art Centre at Yirrkala on the Gove Peninsula in far north east Arnhem Land and you will certainly encounter varied expressions of gurruṯu, though Yolŋu people are likely to tell you that outsiders will never quite comprehend the ideas and feelings underpinning it. “This is a system that connects things across time, across relationships,” says curator Nici Cumpston, an artist and curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island art at the Art Gallery of South Australia. “They can show us elements, but we are never going to be able to understand it all. This is part of the very essence of who [Yolŋu] people are. All of the art is a part of gurruṯu – but gurruṯu is the universe. Gurruṯu is the shape of their world.”

Cumpston, who is of Barkindji Aboriginal, Afghan, Irish and English heritage, has been to the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre on numerous exploratory visits, and there she has developed an understanding of the art work produced by some of the artists. Many of these Yirrkala artists will be showing work in the Adelaide exhibition Gurruṯu, a centrepiece of this year’s Tarnanthi, Australia’s largest annual festival of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island art and culture, for which Cumpston is artistic director.

What is intriguing about much of this work is the way it adheres deeply to Indigenous tradition, and to the connections espoused by gurruṯu, but at the same time manages to be wildly exploratory and inventive. It is amid this work that non-Yolŋu people might surprise and question themselves in finding they have preconceptions about what Indigenous art can be. The answer, of course, is that Indigenous art is as varied and unique as the Indigenous people who make it. And tradition is a living thing, gathering layers through time over its firm bedrock: this is evident in the evolving expressions contributed by contemporary Indigenous artists from across Australia and its islands, from inner-city centres to the most remote parts of the country – including Yirrkala.

The Yirrkala area’s post-colonial history is marked by the 1935 establishment of the Methodist Overseas Mission, which drew Indigenous people to settle at the site permanently; people whose ancestors had inhabited the region for many, many thousands of years. Through the mission era, commercial sales of Yolŋu bark paintings were encouraged, and the artists used this as a way to start presenting their ancestral narratives to outsiders.

Two major events occurred in the early 1960s confirming the power of local art as a political tool. Various clans joined forces to paint ancestral narratives of their respective Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties on three-metre high panels in the Yirrkala church; and in 1963, they produced the famous Bark Petition, on display at Parliament House, which was sent to the House of Representatives when it was announced a parcel of land near Yirrkala was being sold to establish the Nabalco bauxite mine (along with a town of 4000 people), even though Arnhem Land had been declared an ‘inviolable’ Aboriginal reserve in 1931. The mine went ahead, but the petition, according to the National Museum of Australia, was the catalyst for the landmark Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act in 1976.

The Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre was established at Yirrkala in 1975 and incorporates a gallery, studios, and both the Mulka Project (a production house and cultural archive) and the Yirrrkala Print Space, set up in 1995. Cumpston describes the entire centre as being designed in such a way that artists can be in one space but see through to another. “Nothing is hidden,” she says. “The place is alive and has a really great energy.” At the Tarnanthi festival, she is hoping to recreate some of the essential atmosphere of that space.

Much of the Yirrkala history and the vitality of the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre informs the creative approach taken by the artists in the Gurruṯu exhibition. Among the many artists showing are the internationally acclaimed Djambawa Marawili, painter and digital media innovator Wukun Wanambi, and Gunybi Ganambarr, the winner of last year’s Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, who is described as an ‘inspired maverick’. Cumpston says they each question the limits of tradition in their own way, especially in their use of materials and forms.

“The artists want to show the work for what it is and who they are,” Cumpston says. “They are really innovative – they are taking things and twisting them, they are not sticking by tradition. But, at the same time, tradition is embedded in everything they do. That is what is so exciting. They are saying ‘how can we show people that, yes, we are from a bark-painting tradition – but look what we can do with it’.”

Ganambarr is one of many Yolŋu artists known for taking the sacred designs traditionally imprinted on barks and larrakitj (memorial poles) and transforming them into a more contemporary realm for broader audiences. Ganambarr innovates by using unexpected materials with connections to mining and industry, and in this way comments on how Aboriginal land rights have been eroded. Cumpston says Ganambarr uses materials from his homeland where a processing plant for the bauxite mine once was. All the refuse from that plant is lying around this territory, everything from conveyor belts and machinery parts to mysterious pieces of old metal, discarded silver-foil insulation and dumped satellite dishes. “He talks about walking through that Country and how it looks like a spaceship has crash-landed and exploded,” Cumpston says. “It’s like alien material from somewhere else has been scattered throughout his homeland.”

Ganambarr takes these disparate items and carves into them using traditional mark making. This is very painstaking work and Cumpston has been impressed by how methodical he is. One day she watched him doing his carving out the back of the Buku Centre. “It was quite mesmerising – I imagine it is meditative for him. And the work itself is really beautiful.”

In her 1995 book Djalkiri Wänga – The land is my foundation: 50 years of Aboriginal art from Yirrkala, Northeast Arnhem Land Gillian Hutcherson writes that there are many strict rules about the way Yolŋu work with traditional designs – clans guard their sacred designs carefully, viewing them as powerful spiritual manifestations that must not be used by others.

Yet the approach to the use of materials has changed over the decades. Cumpston says Elders insist artists cannot use anything other than the materials of the land and the place where you are from, in this case being very specific to people from Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka. But Ganambarr, Cumpston says, asserts that the found materials from the mining did indeed come from his homeland: if he did not use them, they would be landfill. This encompassing approach is accepted and encouraged by his people. Likewise, Noŋgirrŋa Marawili has produced a group of barks using a special pink ochre – an arresting colour created by mixing natural ochres with the leftover magenta ink found in photocopier cartridges.

Also interested in creative use of colour are Garawan Wanambi and Manini Gumana who have been creating larrakitj painted with a delicate palette of ochres – soft pinks, oranges and blues that have been eked from places around the local area. And Dhambit Wanambi and Yalanba Wanambi have created another suite of larrakitj, but painted them with a black, shimmering sand sourced from their land. “It is like glitter,” Cumpston says.

While this all expresses some aspect of gurruṯu, Cumpston reflects that even she, having steeped herself in the many works and the artists’ way of working, is not an ‘expert’. “I feel like I am in kindergarten, just learning,” she says. For many people visiting Tarnanthi and Gurruṯu, it may be the case that they have to suspend the Western way of thinking that they have to know everything. As Cumpston observes, Western culture tends to be suspicious when something cannot be pinned down in logical detail: truth and authenticity are questioned if we cannot fully understand. Letting go and falling delightedly into some understanding of gurruṯu might be a wonderful relief.

Tarnanthi is at the Art Gallery of South Australia (18 October— 27 January 2020), City Wide Festival (18 October—27 October) and Tarnanthi Art Fair (18 October—20 October).

This article was originally published in the September/October 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.