Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

During an interview for her novel On Beauty, the British writer Zadie Smith mentioned a problem she was trying to unravel: why do we mistake the beautiful for the good? From Ancient philosophy to now, the beautiful has been synonymous with the desirable, the moral and the true. Where is the appreciation for the unconventional and outright unappealing? This train of thought – of re-thinking what we declare beautiful and good, and whether the two should be so tightly melded – is a central line in Patricia Piccinini’s art.

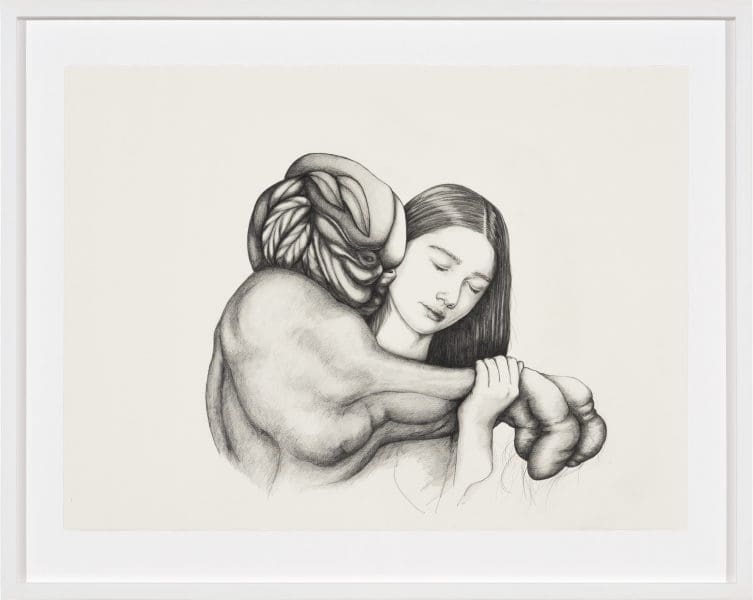

Famous for her sculptures of life-size hybrid creatures, which she calls chimeras, Piccinini places human and non-human creatures in relationships that are as loving and empathic as they are unnerving. A woman cradles a pig-like human baby; a young boy, with softly closed eyes, embraces a sagging older creature, as her grey hair spills over his lap. Sincere without being sentimental, the works feel bound in a narrative scene of intimacy and wonder; they’re more literary than sculptural.

Her newest creation, called Sapling (showing in The Gardener’s Eye at Roslyn Oxley9) depicts a plant-like creature, with a face made of foliage, sitting atop the shoulders of a smiling man. “This relationship potentially could be paternal because that’s what fathers do with their children,” explains Piccinini. “They put them on their shoulders.” But look at the closeness of their heads, the intimacy. “You only let other people close to your head if you’re very familiar with them, if you feel safe with them,” she says. “Children intrinsically know that.” Within the stillness of familial love, the underlying question for Piccinini is this: “Is it possible to have a paternal nurturing relationship with a kind of plant?”

While creating Sapling Piccinini was reading Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer, which weaves stories of motherhood, ecology and Indigenous tradition, prompting Piccinini to depict a nurturing relationship between a human and plant-like chimera. Yet Piccinini, a great and wide reader, also refers to science journals, understanding how contemporary research is cementing the idea that plants communicate with one another. “They do nurture other plants that are not even their own species,” she tells me. “And they do look after their small progeny. They nurture for 80 years sometimes.”

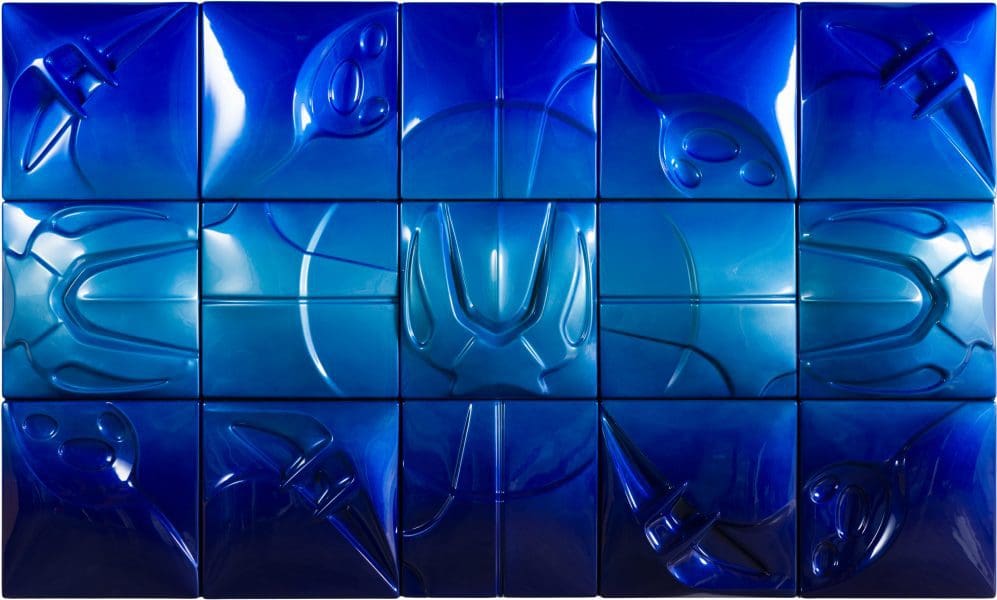

At first glance this amounts to a common lesson of seeing nature as having both difference and agency; of not objectifying plant and animal life. “We see plants as little more than machines to produce food for us, or produce resources for us. We can control them and manipulate them,” says the artist. “But how has that worked out for us? Now we’ve reached a point of crisis where the world is warming up and the whole environment could collapse.” Piccinini’s art – from her recent drawings to her Shoeform sculptures of plants growing out of stiletto heels – considers how the beauty of plants, and the beauty of connection between plant forms, is something to appreciate for its own sake.

Yet this isn’t to say Piccinini is puritan about our relationship to nature: she equally acknowledges the artificial and technological. “A big part of my practice is not just that technology is changing nature, but the converse of that, which is just as important, is that technology is a really integral part of our lives and it has become really natural to us,” agrees the artist. As the dichotomy between the natural and the artificial collapses, a space is opened to consider the ethical implications of living with and between the two, and Piccinini’s art plays within this space, imagining the possibilities.

In reorienting our sense of beauty and living through the messy blend of the natural and artificial, I mention to Piccinini how I find something stressful, almost pessimistic, in her work. Take a sculpture like Sanctuary, where an ageing woman is being stoically carried by a large, bear-like chimera; is this scene tender or loving, or is it a master-slave situation? What’s unnerving, I later realise, is how it conveys that empathy is a choice and not always a natural given. The ethics of empathy is in its cultivation, especially for what isn’t considered conventionally beautiful or good.

In recognising this, the power relations between human and non-human creatures are laid bare. “Yes, that’s in there,” says Piccinini, “and it’s intentionally there because they [the chimeras] have a vulnerability and that’s a big part of the equation. I have to depict this vulnerability because it can’t be like they are these belligerent gods that have power over us.” The long history of sculpture has often been about portraying the virtue of human power, whether in Ancient Greek bodily forms or even many of the stark abstract sculptures of the 20th century. When vulnerability is brought into the equation, essential questions come with it: “What is our responsibility to other creatures? To non-human creatures? What is our duty of care?”

Empathy, and the ethics of cultivating empathy, has been the root of Piccinini’s art for the last 25 years. “Exactly,” agrees the artist. “For years, my practice has been interested in how we relate to difference and how we understand our changing nature and changing environments. So that’s why I’ve often depicted chimeras. It can represent not the normal standard of beauty or intelligence that’s lauded in our world or in the art world.”

The Gardener’s Eye

Patricia Piccinini

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery

20 August — 19 September

Watch Patricia Piccinini discuss her new work Sapling here.