Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

In the 1980 historical drama, The Elephant Man, the titular character John Merrick is chased by a mob into a railway station toilet. Finding himself trapped by the baying crowd, Merrick screams, “I am not an animal! I am not an animal! I am a human being!” While the real Joseph (not John) Merrick who lived in Victorian London was a man with a disability, the creatures that artist Patricia Piccinini presents are not limited to the binaries of human and animal.

Piccinini’s work consists of carefully detailed chimeras; her mostly mammalian life forms are seen to breastfeed or nurture other creatures, or perhaps they are doted on by loving human grandmothers, like in the photograph Library, 8:45pm from the Fitzroy Series, 2011. Despite the question of human-animal hybrids dredging up ethical dilemmas, the works avoid moral grandstanding. While Merrick toured the freak show circuits of the time, Piccinini’s creations tour the world of art fairs. She made a splash at the Venice Biennale in 2003, and her survey show in Brazil in 2016 is still touted as the most visited contemporary art show. We look upon synthetic flesh, real hair, or steel, and the sweet tableaux they are arranged in. That they are ‘loving’ yet monstrous triggers questions about their raison d’être. They are not without a certain bearded lady appeal, too.

Hester was born in 1920, Piccinini in 1965; the artists are separated by almost half a century, but it is the gulf between their recognition and success in their lifetimes (Hester’s exhibitions were critically panned, she was not materially successful and received financial support from Sunday Reed) that holds the biggest deviations in their trajectories. Although Piccinini is said to idolize Hester, Through Love is often a clash of frequencies.

Hester’s paintings are fast works. She liked to work while sitting on the floor, frenziedly working with ink brush and wash on paper. She was among the first artists in Australia to engage with the Holocaust, one of the darkest manifestations of humanity’s desires. In her Gethsemane series, 1946-1947, her human faces become the canvases that wear the unspeakable horror of concentration camps.

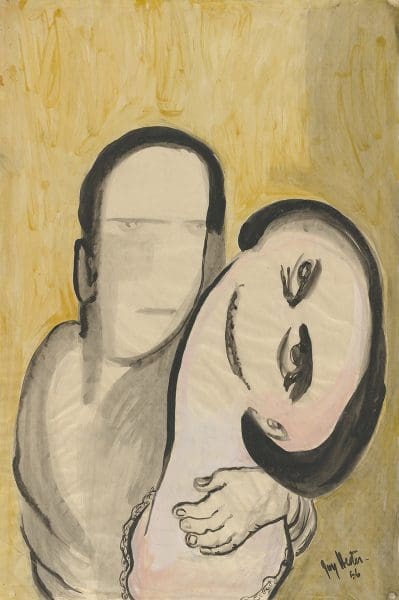

Though of course in Through Love, it is love not war that is under examination. Looking at the commonalities between the curated works, both Hester’s and Piccinini’s works present love that defies boundaries. Hester’s show the intensity of male-female love as collapsing the individual; the faces in the Lovers series become amorphous in partnership. Drawn in the 1950s, the figures retain a distinct darkness, as though the stain of World War II cannot be washed out. In Lovers (IV), 1955, a woman looks up to the sky in rapture, or terror, as a man shadows her in the background. The woman’s upturned nose resembles the upturned snout of the orangutan-mother in Piccinini’s Kindred, 2018, positioned in front of it. Both artists have stretched the human form, each to their own end.

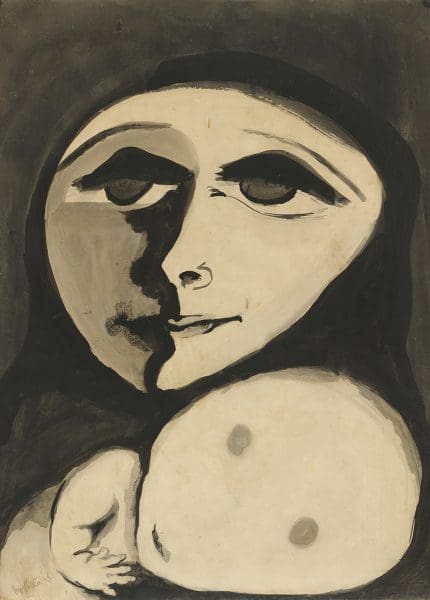

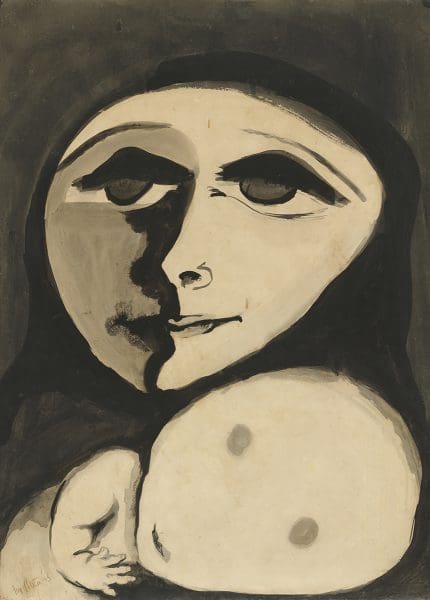

While there is a deep affection for motherhood in Piccinini’s works, as though in its wet-eyed bliss it is relatable across species, Hester’s view is ambiguous. Mother and Baby, 1955, depicts the mother ogling her baby, with her eyes literally popping out of her head. The baby is barely a wash of grey, so new and unformed. The fear, the fragility, and the shock of holding your child is in this work so recognisable it belies the almost crude execution of the portrait.

Sanctuary, 2018, was created especially for Through Love and is installed in the room furthest from the entry. While normally I look forward to reaching this room for a brief respite and to take in the panoramic views from the windows, Piccinini has covered the floor to ceiling glass with opaque red film. Two figures are positioned with their backs to the entrance, requiring the viewer to enter deep into the room that envelopes the viewer and pulses red.

Saggy, naked and covered in downy hair, the elderly couple in Sanctuary are frozen in a tender embrace. They are engulfed by the size of the room and seem to hold each other for support. It was a gruelling press day with a 5am start when I saw the exhibition. Piccinini was putting on a brave face for the media queuing to quiz her. Speaking about the unashamedly ageing figures depicted in the sculpture, she was quite visibly moved.

In Frederick Treves’s 1923 book The Elephant Man and other reminiscences the author recalls how he persuaded his friend, a “pretty widow” to visit Joseph Merrick. After she smiled at Merrick and held his hand at their first meeting “he let go her hand and bent his head on his knees and sobbed until I thought he would never cease.” Our need to love and be loved is pretty much universal.

Patricia Piccinini and Joy Hester: Through Love …

TarraWarra Museum of Art

24 November – 11 March 2019

Listen to Patricia Piccinini discuss her work in our Podcast here.