Speaking about 19th-century British arts and crafts advocate William Morris for BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time, Marcus Waithe said “he wanted to reunite intelligence and freedom with the work of the hands; to put art at the forefront.” The Australian Tapestry Workshop (ATW) is a rare contemporary harbour for the kind of production Morris championed in which creative autonomy, beauty and pleasure are not alienated from hard work. “Few workshops are left,” explains public programs coordinator Sophia Cai. “It’s about preserving the integrity of handmade, time-intensive work.”

Painting with Thread at the Australian Design Centre is a portrait of the spirit and industry of the ATW and its weavers.

Two significant tapestry commissions represent the final chapters in a longer story of collaboration and technique, which is told with weavers’ bobbins, Australian yarn (dyed in-house) and a trove of preparatory samples and colour strips.

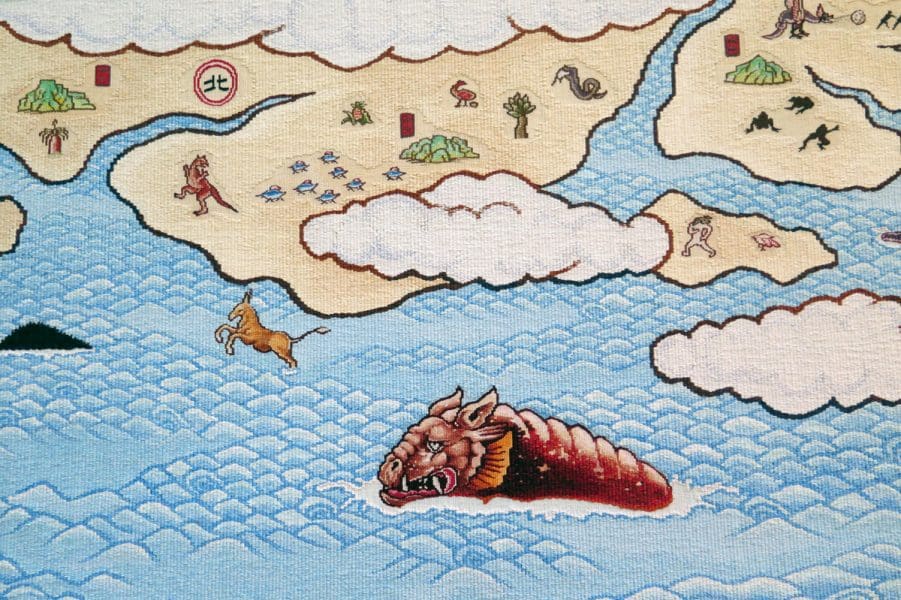

Most of this behind-the-scenes material relates to Treasure Hunt, 2018, a ficto-cartographic seascape designed by Guan Wei. Spanning a monumental 3.6 metres, it took weavers Chris Cochius, Pamela Joyce, Jennifer Sharpe and Cheryl Thornton 1360 hours to complete. Its surface is populated with fantastic beasts (both Australian and Chinese), rolling waves and map symbols. “You find yourself navigating it left to right,” says Cai, “like a scroll painting.”

The relationship between designer and weaver is astoundingly granular. There is no distinct handover: all details must be translated, even resolved into tapestry collaboratively. “It’s complex,” explains Cai. “The weaver’s interpretation is nuanced and individual.” Sample weavings are essential to this process. A bit like “sketches for a painting, they inform decisions about colour, thread weight and pattern.” Samples are also decidedly popular: to display them is to pull back the curtain and reveal the magician’s trick. As Cai says, “A finished tapestry can look magnificent and complete. Samples help to illuminate its handmade origins.”

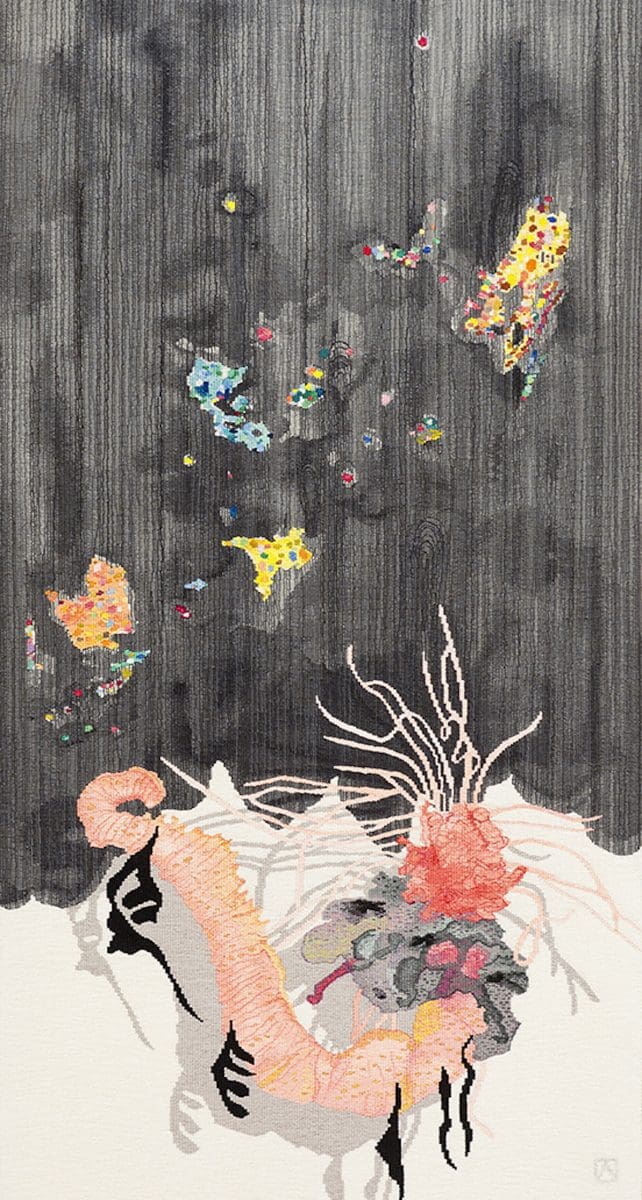

Sangeeta Sandrasegar’s Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky, 2014, was designed as a papercut featuring delightfully weird deep-sea forms. Weaver Sue Batten translated it into tapestry, richly textured with soumak stitching. Created for an exhibition at Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh, the work ponders exchange across oceans and cultures.

While Painting with Thread demonstrates the flexibility of contemporary weaving, its two seascapes tell similar stories: girt by sea, Australia is a crucible of interaction between Indigenous culture, post-colonialism and migration.

Sangeeta Sandrasegar and Guan Wei both offer complex alternative visions of Australian identity in which mythology overlaps with history and the ocean flows symbolically between conciliation and conflict.

The exhibition also reveals the emotive power of tapestries. Tender associations with intergenerational tradition and the home are compounded by the way they “insulate rooms and soften sound” says Cai. Tapestries also result from devotion, from a weaver’s unwavering labour. It is no coincidence that Penelope’s fidelity to her absent husband Odysseus was symbolised by her tapestry. Nor that Lucretia’s courtly virtue was proven by her preference for weaving over partying with the other Roman army wives.

The Lady and the Unicorn tapestry cycle, recently shown at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, is the archetypal tapestry, responsible for medieval associations of concealed passages and regal bedchambers. While the ATW still uses the same Gobelins technique, invented in Reims in the 15th century, the studio is decidedly forward-looking. “Our weavers work with living artists, to produce new perspectives and approaches, revitalising this medium for a contemporary audience,” says Cai.

Painting with Thread: Tapestries and Samples from the Australian Tapestry Workshop

Australian Design Centre

2 August – 26 September