Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

For the Ngaanyatjarra people of the remote Warburton community in Western Australia – 1050 kilometres west of Alice Springs, sandwiched between the Gibson and Great Victoria deserts – there is no word for art, and no word for artists. They paint or occasionally render in glass and wood their totems and dreaming stories, to ensure the continuation of their culture. The community decided to keep most of these cultural documents, so it is rare to see Ngaanyatjarra art on the market.

Sydney University has launched a portal about the Ngaanyatjarra world, created in consultation with the community, its contents approved by elders. Containing images of about 1000 artworks, including more than 900 paintings, as well as video interviews with artists and audio recordings sharing knowledge inherent in the works, the portal provides rich, dynamic insights. Currently it can only be accessed by Sydney University staff, students, and Warburton community members, but it is possible that access will be given to a broader audience in the future.

Language and culture have remained intact among the Ngaanyatjarra because the remote community has only had contact with Western culture for about 70 years. The portal is intended as an educational tool, with community members approving the continued use of the recordings of their voices on the site after they pass away, says Panos Couros, production manager of the Warburton Arts and Knowledge Project.

The community started using acrylics in the late 1970s, the best part of a decade after Papunya Tula artists pioneered their use in Indigenous communities. A non-Indigenous man, Garry Proctor, devoted himself to managing and promoting the cultural life of Warburton.

“Their style of paintings is a little bit different than other people’s styles, in their use of colour and use of very condensed dots,” says Couros. “They’re not like the APY lands or Papunya works or any of the other places.”

Epic dreamtime stories for the Ngaanyatjarra include the Seven Sisters (Kungkarrangkalpa) and the Two Snakes, Father and Son (Warnampi Kutjarra). Mythical beings (Tjukutjaja) such as the Eagle Man (Pilpangka), the Crow Woman (Minyma Kaarnka) and the Cockatoo Woman (Minyma Kakalyalya) meanwhile constitute more localised stories.

The project has taken three years to bring to fruition. Future additions to the portal will include nutritional analysis of seeds of plants referred to in the paintings, currently being undertaken by the university’s agricultural department, says Couros.

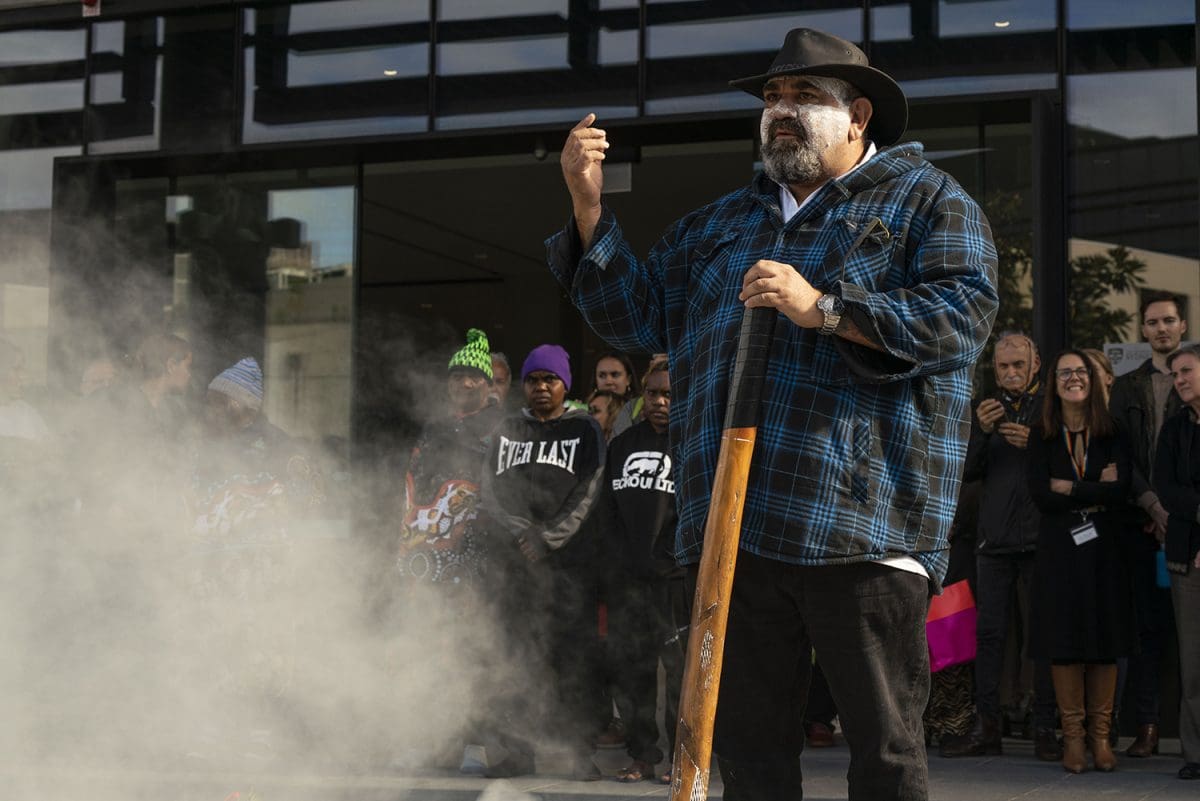

Six female Warburton community members travelled to Sydney during NAIDOC Week to launch the portal, including four artists – Elizabeth Holland, Christine West, Madeline Jackson and Philippa Butler – who have been working on campus, painting a large canvas.

“A lot of the active people who paint at Warburton at the moment are women, but they’re trying to get a resurgence of men painting,” says Couros. “A lot of the old men who painted have passed on. All of their works are astounding. You’ve got to see them to believe them; images don’t do them justice.”