Cartographies of the heart

Five Acts of Love, a new exhibition at ACCA, maps the space in which memory, intimacy and resistance intersect.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Jeune femme se baignant (Young woman bathing), 1888, oil on canvas, 81 x 65.5 cm. Private collection.

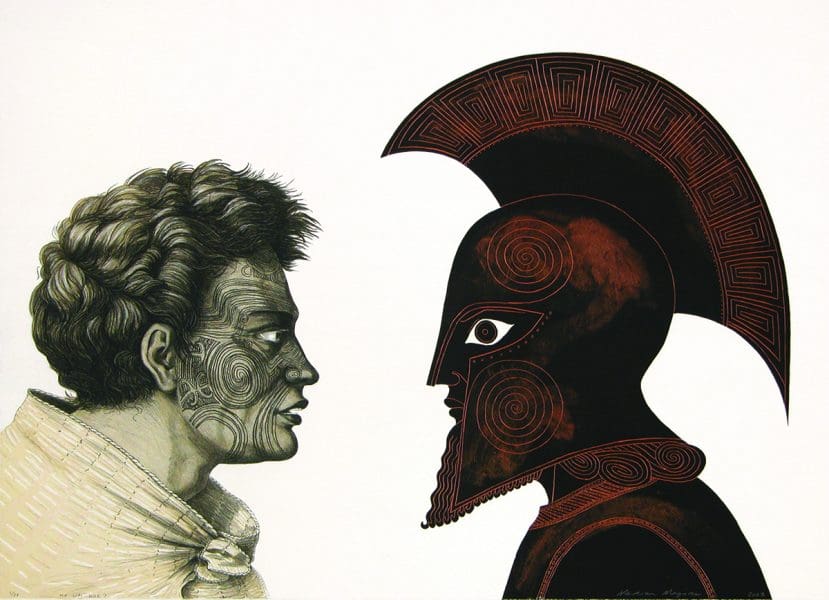

Marian Maguire, Ko wai Koe (Who Are You?), from the series The Odyssey of Captain Cook, 2005, lithograph, 51 x 70 cm. © Marian Maguire. Courtesy of the artist.

Berlinde de Bruyckere, PXIII, 2008, wax, epoxy, metal, rope, 167 x 51 x 100 cm. MONA © Berlinde de Bruyckere. Photograph by MONA.

Ryan McGinley, Anne Marie (Iguana), 2012, c-print, 114cm x 76cm. Courtesy the artist.

Balint Zsako, Untitled, 2006, watercolour on paper, 40cm x 30cm. Copyright Balint Zsako. Courtesy the artist and Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania.

When you visit Mona, it is difficult to avoid art that reflects biology and its functions. There’s Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca Professional (affectionately dubbed “the poo machine”), a glorious yet pungent mechanism that mimics the process of the human bowel from stomach to deposit. Greg Taylor’s pristine white casts of vulvas have recently been back on display and, if you’re lucky (or unlucky), you’ll discover a secret toilet that privately displays your seated nether regions on a wall in front of you.

Charles Darwin liked these themes too. Earlier this year, Mona owner David Walsh admitted in an interview with Jennifer Byrne that he has always been, like Darwin, “obsessed by evolutionary biology”. The result of this obsession is Mona’s summer exhibition, On the Origin of Art – Walsh’s chance to further explore evolution and how it connects to the creation of art. “To understand what art is, we first have to understand why it is that we make it,” Walsh said. “Art is universal, and modalities of art cross cultural boundaries. That’s an indicator that the roots of art lie beyond, and possibly before, culture. Art also often engenders emotional responses, and anything that engages emotions has an evolutionary component.”

To investigate these ideas, Walsh has recruited a group of researchers he labels as “biocultural scientist-philosophers”. For On the Origin of Art, Steven Pinker, Brian Boyd, Geoffrey Miller and Mark Changizi all create arguments as to why we make art. Individually they illustrate their conclusions about art in four separate exhibitions within Mona.

To piece together their contributions, these biocultural scientist-philosophers have sourced work from the Mona collection as well as state galleries and private collections in the UK, Europe, the US and Japan. The exhibitions are wide-ranging in their scope of media and include paintings, antiquities, audio-visuals, ceramics, textiles and contemporary installations. Several new commissions are also involved and, at the time of writing, were yet to be revealed. “I’m setting up a framework for asking interesting questions and I’m asking these questions of people who aren’t usually engaged in an art setting (evolutionary biologists, social scientists, neurologists),” said Walsh.

Steven Pinker, psychology professor from Harvard and one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world today, approaches his chosen selection from an extensive background in language and cognition. Pinker asks us to consider whether art is a by-product of status, consumption and fashion. He describes art as a “pleasure technology”, an invention of human enjoyment and satisfaction that exists for no other reason.

Comparatively, leading expert on literature and evolution Brian Boyd looks at art as a form of cognitive play, particularly through the use of pattern. He also suggests art stems from a “signalling system”, a feedback loop conveying information between artist and audience and vice versa.

Geoffrey Miller, a professor from the University of New Mexico with an interest in evolutionary psychology, threads the content of his exhibition around sensory consumption and attraction. Much like the bowerbird discovering that decorating his nest helped attract a mate, Miller implies the origin of art lies in a connection to reproductive rates and aesthetics.

Taking a more historical view, theoretical neurobiologist Mark Changizi’s answer to the origin of art lies in the invention of civilisation. Rather than a purely instinctive impulse, Changizi believes the production of art to be linked to influential elements of nature and our immediate environment.

Strongly positioned to offer a scientific perspective of art rather than a culturally specific view, On the Origin of Art is an ambitious and intriguing attempt to answer complex questions. They are the questions that spurred Walsh to start collecting and to create Mona. Can biology really be a driver of art? Can we process art from another perspective completely unrelated to culture?

Offering answers is quite a departure from Mona’s usual penchant for avoiding explanations of art and encouraging viewers to come to their own conclusions. As Walsh put it: “For the moment I’m just trying to show that art is a complex thing and its characteristics multifarious. Curators, typically, weave a cultural web. But the web of art, like the web of life, has evolution at its genesis.”

On the Origin of Art

Museum of Old and New Art (MONA)

5 November – 17 April 2017