It was the German artist Joseph Beuys who famously said that “every human being is an artist.” These oft-quoted words reflected the artist’s belief in the radical and transformative power of art, where “every sphere of human activity, even peeling a potato, can be a work of art as long as it is a conscious act.” Beuys would later coin the phrase ‘social sculpture’ to describe his concept of art being embedded in every aspect of life—meaning that everything is art and, by extension, everyone is an artist.

While there is some optimistic comfort we can take from Beuys’s words, I wonder if it is truly possible for our experience of art to realise this idealism. Our engagement with art is often mediated through some form of structured exchange—its methods of display, its distribution, or the social networks that create what we know as the ‘art world.’ In other words, there is art, and there is the culture of art, one that has certain protocols that determine whether we consider something as ‘art’—and it is this intersection that I am interested in thinking about.

This isn’t a question about mere definitions of art—it is a question of how we can imagine it.

2020 was not a kind year (and that is a generous understatement), and the impact on the arts and culture industries still remains to be seen. The devastating health crisis of Covid-19 has further exacerbated long-entrenched structural issues of racism, sexism and class privilege; we have witnessed a global arts industry grappling with these issues while simultaneously fighting to stay afloat. From calls for institutional accountability (see Instagram account @changethemuseum), to artist-led protests against mass job losses and cuts, to rethinking access, audience, and participation through digital channels, it felt at times like we had truly reached a tipping point. It became a matter of not only daily survival, but also a matter of possibilities: what kind of post-Covid future(s) might art and artists be a part of?

In Melbourne, after a year mostly spent collectively in lockdown, I have been forced to think more critically about the role of art—why it matters, and continues to matter. As a curator and writer who doesn’t make art, my experience with art has always been through external engagement. Spending six months unable to physically experience art exhibitions except through screenshots—where every interaction was mediated through my overworked laptop screen, where my daily walks with my dogs within the 5km radius became my whole world—has shifted my day-to-day priorities and recognition.

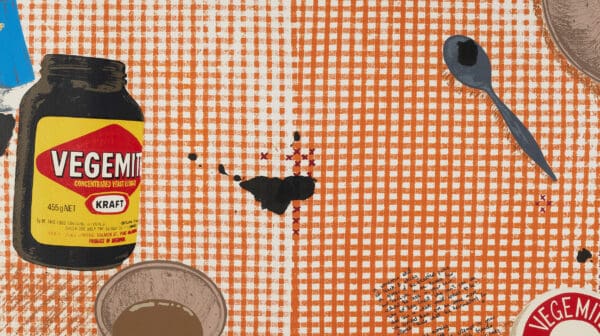

Because while I dearly missed art, in hindsight I don’t think I ever truly went without it. I still experienced and saw so much creativity—and I don’t mean just online exhibitions or artist talks, although there was plenty of that. From handmade ‘villages’ of spoons installed at my local park, to dance videos shared through text messages, to visiting virtual islands in Animal Crossing, all of these activities of human endeavour and inspiration stayed with me.

Thinking back on Beuys’s words, I wonder whether the truth of his claim lies in the fact that artmaking will—and must—persist in these creative acts of the everyday, rather than the larger structures that hold the art world in place. I’m not saying that museums, galleries, universities, exhibitions and art fairs are unimportant and we should get rid of them, but can we perhap see in their recent absences something of a different value: how art is a fundamental way of experiencing human life that occurs in day-to-day life, not just in rarefied spaces.

This isn’t, however, a clear-cut task. In trying to widen our scope of what we consider art, and embracing the creativity that comes from the sheer act of living, there is the question of how we can fully realise the idealism of Beuys’s words in an existing culture where art’s significance has historically been marketed on claims of its exclusivity and importance. This history is also one of the reasons why the halls of art history are predominantly filled with white men, because the input from women and people of colour is often undervalued as something without significance. Art’s ‘specialness’ has always been connected to what it was not, as much as what it is. But recognising the limits of this narrative—how our cultures of art shape but also restrict what is imaginable—can offer us a bold agency to reclaim what has been previously denied.

So, my question to you is: what might art without this culture of ‘significance’ look like? Is cooking a meal for our loved ones a work of art? What about completing our daily chores, caring for family, taking a long walk around the neighbourhood, or knitting a beanie for a friend? Are the choices we make, the daily actions we pursue, a form of world-building and therefore art-making? The ordinariness that I think of here is perhaps what makes art extraordinary, as something we do as part of everyday life—as necessary as breathing, eating, sleeping, and loving. And that makes it not just important, but also essential.

Perhaps in my very small socially-distanced lockdown bubble, I had in some way escaped, even if temporarily, the structures of art that kept us down. But I gained something else along the way: a kind of affirmation of what art means to me. As we cautiously return to a new ‘normal’, the lesson I take with me is that art will persist whether or not our current cultures of art do, and that there is power in recognising art as a verb, not a noun. I hope we see how gate-keeping only keeps out possibilities not even yet considered, and that a future is one where multiplicities can, and should, exist simultaneously.

This is what gives me hope.