At first I saw only spidery, matte black forms: these were not the banksia I knew from bushwalks and suburban gardens. Studded with ruby, the familiar conical flower heads grew into new, bony wings, spreading and sprouting across the white walls of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA). Created by K/Gamilaroi artist Penny Evans, gudhuwali BURN, 2022, stood totemically at the entrance of the recent 4th National Indigenous Triennial.

Threatened by clearing, disease and bushfires, 170 fire-germinated banksia species are essential fodder for all kinds of nectarivorous creatures around the coastline. By sculpting in terracotta and kiln-firing the wildflower’s spiky shapes, Evans’s work directly refers to the 2015 and 2019 bushfires. It also seems to me a powerful rejection of the haunted history of imperial botany—Sir Joseph Banks’s narcissistic naming and taxonomising of the wildflowers during the Endeavour voyage in 1770.

Banksias are often positioned, critiqued even, as icons of Australiana, harking back to May Gibbs’s children’s illustrations (a jokey homage to the banksia by local fashion label Romance Was Born also featured in Know My Name at NGA, a few rooms away from Evans’s work). Evan’s art is a tonic to view the banksia through the tenacity and evolution of Country, and the consequences of neglecting traditional ways of caring for it.

Absent in the wall text was any mention of Australia. In fact, the word was almost completely absent from most of the show’s texts. Colonialism was mentioned often. Assimilation and relocation. Evangelical enterprise and pastoralism. The exhibition spoke of collective forms of being—but rarely the concept of the modern nation that we now call Australia.

It wasn’t just a cleansing experience in a taxing year of #auspol and #democracysausage. Beyond notions of nationhood, there remains a lot of space to explore ideas in art, especially when it comes to Country, landscape, history, identity, internationalism, collectivity and the future. And yet it often seems as though artists must relate to national identity to catch the attention of institutions, gatekeepers and prizes. Notice how the sponsor message on the country’s biggest art prizes, the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman, primarily refers not to form or artistry but “Australian life”.

This landmass has a timeline that long predates the idea of the nation-state. “Australia is a continent, not a country,” writes Ambelin Kwaymullina in Indigenous Peoples as Subjects of International Law. First Nations art connects us to tens of thousands of years of living history and continuous culture here. Anywhere and everywhere, art predates national borders.

The concept of the nation-state first appeared in 1648 and was entrenched as the dominant form in Europe by the 19th century. On this continent, British imperialism and settlement triggered Indigenous displacement long before desires for a new nation began. The idea of being Australian became popular by the 1830s. Calls to unify the colonies surfaced in the next decade, becoming a serious and coherent movement in the 1880s. Federation arrived in 1901, bringing a common border, currency and system of parliamentary democracy to the edge of the British empire.

Cultural policy has been an extension of Australian nationhood since the 1950s. Arts funding is often justified by public agencies as a contribution to the national project of working out who we are and telling our collective stories; Australia Council for the Arts describes its mission as “investing in arts and creativity that reflects and connects the many communities that make up contemporary Australia”.

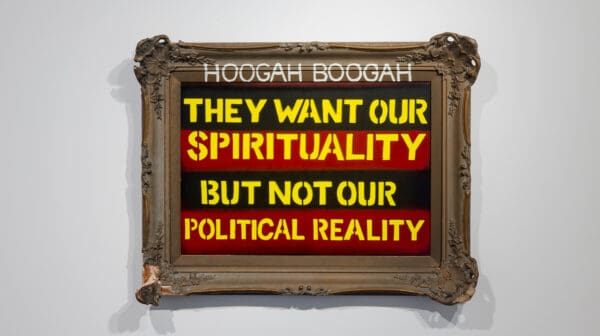

Exhibitions traffic in national iconography and symbols, such as the group show Just Not Australian at Artspace in 2019, a self-described “unwriting of Australian national mythologies”. A repetition of flags and maps—in a graphic, designerly manner—aimed to complicate the notion of one singular national identity. There’s value in this. But even projects promising to complicate national identity can end up subtly reinforcing it, by positioning it as the sharpest lens through which to view life and land on this continent. Expanding national identity through diverse representation is worthy, but nationalised mythologies have always relied on outsiders and absurdities—why perpetuate them, rather than reject them altogether?

Commentators often write that art is a way for the nation to examine its own soul. In that sense, the ongoing obsession with national identity in the arts isn’t just conceptually limiting. It’s also an unconscious guzzling of governmental ideas about the value of art: that art reflects, or should reflect, ‘Australia’. After all, the rise of the nation-state as the modern form of political organisation also brought with it the rumblings of nationalism, which can occur subtly across political thought from left to right.

Many artists have built a practice from Australianising the landscape, by which I mean associating places with modern Australia (Brett Whiteley and Ken Done’s vibrant visions of Sydney Harbour in Eora Country), or diving into colonial history (contemporary practitioners like Liam Benson and Peter Drew).

What flows is the tendency to read a commentary on Australianness into almost every work of art made here, even when such a commentary may be absent. This all-Australian enveloping is arguably most apparent in the local collections of various national, state and regional galleries.

Colonial myth-making abounds in many collections, where Captain Cook often emerges as central to Australian history, rather than, say, an emblem of the British empire. His polished steel visage— rendered by none other than Maori artist, Michael Parekōwhai—looms over the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s Australian collection, but the man did not initiate an Australian national project, nor did he indicate an interest in one. Australia as we know it was far from the minds of those who arrived on the Endeavour and the First Fleet. It wasn’t even a word; Cook was claiming a piece of New Holland for the British Crown.

This approach to national identity stifles thinking about how things could be different. It can obscure hidden histories of Indigeneity, and the specificity of Country—it’s far too easy to conflate “place” or “ecology” with “nation”. It both thwarts an examination of other forces and diverts our imagination from what is really in front of us.