It was artist Jenny Holzer who stated that ‘Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise.’ This maxim is part of her well-known Truism series, using concise one-liners to contest commonly held truths or modern cliches.

Reflecting on this statement more than 30 years later, it still resonates in our current socio-political climate. I’m reminded of Holzer’s words in the ongoing shadow of #MeToo, and the continuing public discourse about how power and privilege are unequally distributed, and change therefore requires structural shifts in the systems we have come to rely on. As an undergraduate art history student, my professor once told me that when writing about art, I should separate the artist from their biography. My role as a writer was not to take the artist’s background and words as gospel, but to judge and value the merit of the artwork on its own. This might have been a simplification of a larger discussion about the intrinsic value of art — the usual ‘art for art’s sake’— but it does perpetuate a mythology of art that is conveyed through our academies, institutions and popular culture.

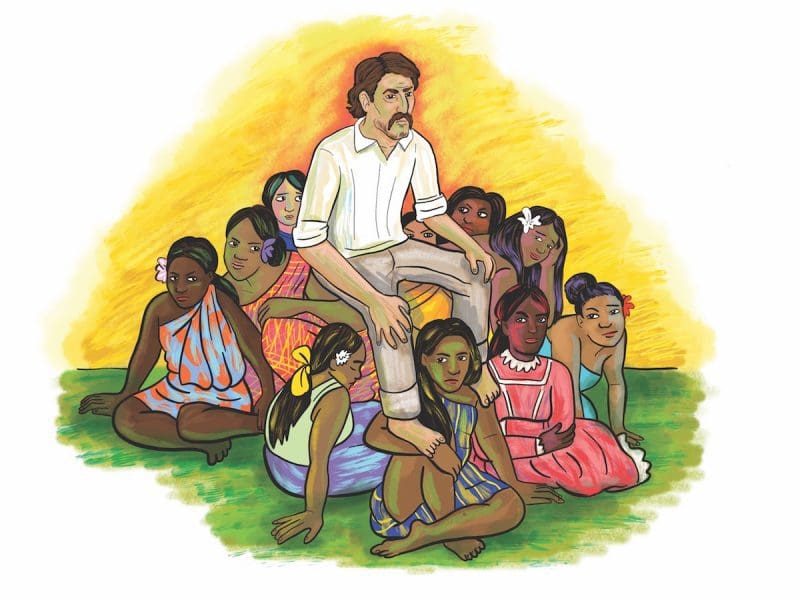

A recent exhibition of Paul Gauguin’s portrait paintings at London’s National Gallery has challenged this accepted narrative by openly acknowledging the problematic history of the artist. The curators directly address Gauguin’s sexual exploitation of the Tahitian girls featured in his work through the exhibition texts and public programs, and thus openly grapple with the moral complexity of Gauguin’s place in an art historical canon when it is at odds with the values of the audience. In other words, do Gauguin’s artistic accomplishments give him a ‘moral pass’ for his predatory behavior?

Do museums have a duty of care or responsibility to uphold ethical standards to the artists they exhibit?

Gauguin is of course not the only artist in history (or in the present day) whose problematic behavior has long been known. History is built on the backs of imperialism, colonialism, exploitation and war, and museums are not neutral spaces that are immune from these powers. Gauguin is an easy example to discuss because of his accepted cultural significance, which also translated into record-setting auction records. Once an artist is so deeply entrenched in the canon, there is more vested interest and cultural capital to keep them there. Simply put, we cannot ‘cancel’ Gauguin that easily.

There is also the myth about the artistic ‘genius’ that feeds into the canonisation of problematic artists. Because art is perceived as an elevated pursuit, the biographies of the artists who create them seem to be above normal societal compasses. At times, it is the notoriety of the artist’s personal life that adds character or becomes part of the popular discourse surrounding their fame (or infamy). Whether that be general bad behaviour like cheating on a spouse (Rivera), to criminal activities like cold-blooded murder (Caravaggio), or sexual abuse (Gauguin), we as audiences are fascinated as much as we are disturbed by these transgressions. There is an inherent voyeurism to this act, which feeds into perpetuating the stereotype of the ‘tortured artist’.

This is why the decision by London’s National Gallery to address the ethical issues in Gauguin’s practice is an encouraging step to see by a major institution. Without giving the curators too much credit, this is a step in the right direction towards greater equity and accountability in the arts. It does, however, still hold space for Gauguin, and continues his prominence in art canon, even if it now includes more acknowledgement of the harm caused by his actions.

In recognising that art history and Western art institutions have centred predominantly on white, male artists for so long, whose voices do we miss when we continually centre the same narratives? What do we lose, or gain, when we stop doing this?

This brings me to my final point, which is a question about what we can do as audiences who love the work of problematic artists. It’s not as straightforward as blacklisting or removing all their work from public display, and I don’t think it is fair to expect art audiences to be a moral compass in this way. Change is structural and needs to come from institutions. We do, however, have the power to be more intentional with who we personally champion, with the living artists we chose to support, whether that be attending exhibitions, buying works by emerging artists or what we tell ourselves about what an artist looks like.

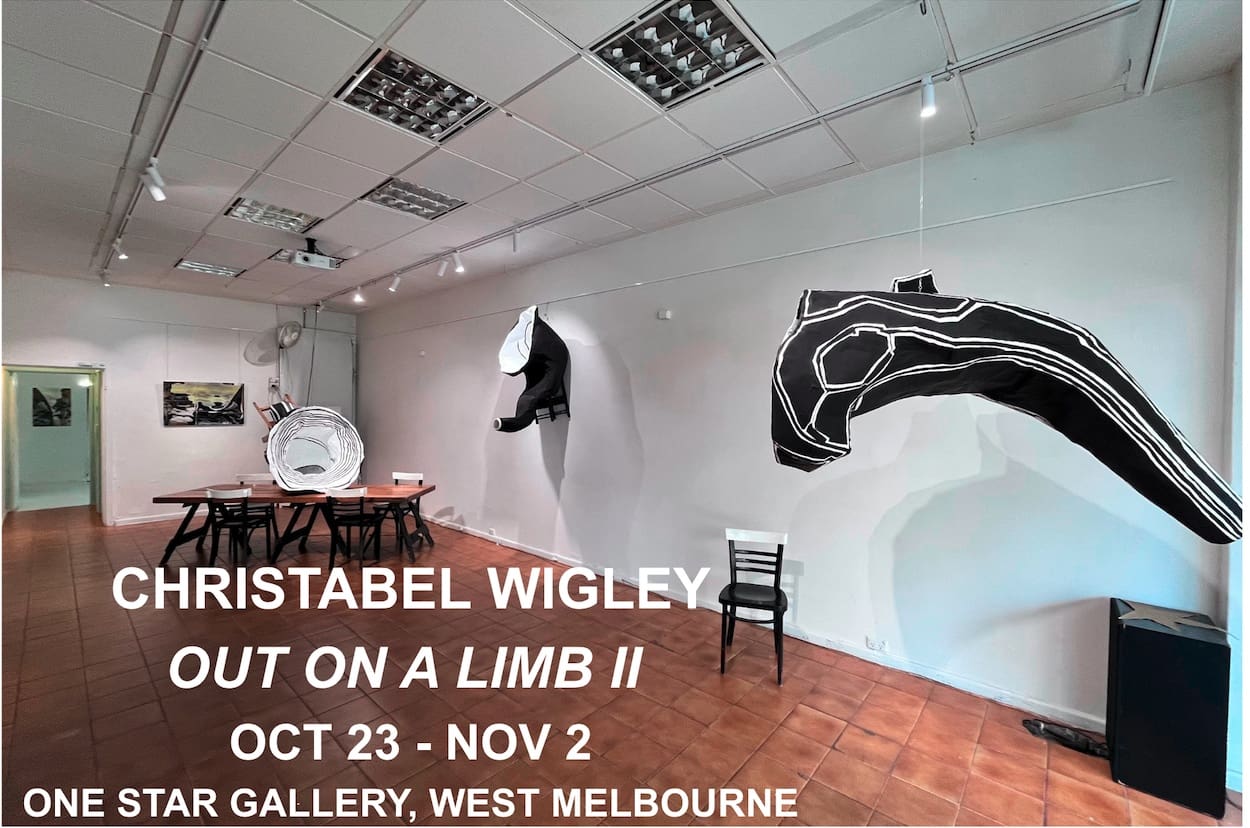

Thinking back on what my art history professor told me about separating the artist from the artwork, I recognise now that a consequence of doing this — unintended or not — protects the status quo. That art, like everything else, is embedded within the social, cultural and political climate it is a part of, where the distribution of power is not equal. We cannot pretend that every artist gets the same opportunity to exhibit. This is how power works; it needs to be relinquished in order to be distributed. One less Gauguin exhibition, one less Picasso exhibition, one less Woody Allen film screening, means one more space for a previously underrepresented voice.