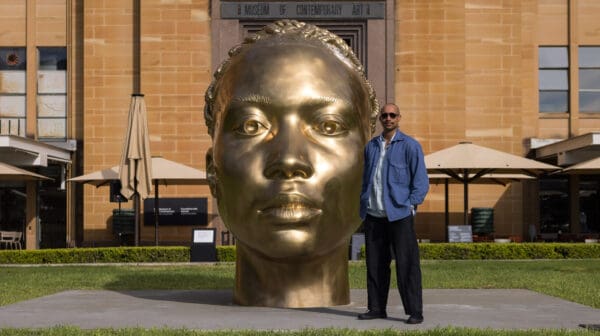

Vishal Kumaraswamy has a lifelong awareness of the way different kinds of bodies negotiate public space. The acclaimed Bangalore-based artist and curator is part of India’s Dalit community. He was compelled to learn about the way his family gathered together and asserted their agency against the backdrop of caste oppression.

The anti-caste movement sowed the seeds for the exhibition, Okkoota. In Kumaraswamy’s native tongue, Kannada, it means gathering, assembly or alliance. The exhibition, presented by Melbourne’s Arts House, finds a sense of community in disparate histories. It also explodes colonial structures from within.

“I’m the first generation who’s grown up outside caste villages across the country and I wanted to trace those steps back,” he explains. “I started asking my dad about what his experiences were like, started looking at a lot of festivals, processions. What struck me was the way my community were navigating the movement of their bodies. This is a recurring theme across my practice. I often place this in conversation with collaborators who can speak to that experience, who can bring in perspectives that are helpful to see alongside my own.”

The North Melbourne Town Hall, where Arts House and the exhibition is situated within, is a bluestone structure designed in 1876 by English architect George Johnson. It’s a study in the hallmarks of colonial architecture: grand, ornate, imposing.

“I had an idea based on an experience working with another colonial building in the UK and I started asking the question: what is the sound of the voice that is going out of the building? Can that become a starting point if I decide to work with Arts House?” he says.

Over the course of Okkoota, the building will play host to work by 12 local and international artists who share an interest in social justice and transnational solidarity. They include Phuong Ngo, Eddie Abd, Subash Thebe Limbu, Eugenia Lim, Sancintya Mohini Simpson, Nikhil Nagaraj and Kirtika Kain.

Lim says that Okkoota, which also features talks and communal meals, reimagines the building as a space that could welcome marginalised artists. To make the 2022 video work Shelters for Kyneton (triadic transfer), Lim, whose practice has long asked viewers to pay attention to the bodies our culture renders invisible, carried out a series of interventions into Kyneton’s local transfer station.

“Every single household would have some sort of interaction with the tip and it created the sense that it might be one of the most important nodes in the town in terms of the flow of waste and resources,” she says. “It was full of birds and flowers and life forms.”

In the resulting video work, Lim along with two members of the local community—the Macedon Ranges Shire Council Mayor Jennifer Anderson and transfer station worker Steve Boulter—appear in ‘wearable shelters’, gold suits made out of mylar. The material, often used in refugee rescue, reflects a politics of care. But the work also creates a space in which people from opposite sides of social strata could come together.

“I think the artist’s role can be to create these different relationships between people who don’t normally feel they can talk to each other,” she says. “Most of the time if you put the invitation out there, people respond and that can shift the way things are seen and done. That can create some space within the heavy settler colonial context that we have.”

For Kumaraswamy, context is important. The conversation around colonisation that is shaping the art world, he says, often erases different histories and positions in favour of a story that’s simpler and more convenient.

“In all the conversations around decolonising, the thing that is missing is contextualising the effects of colony,” says Kuramaswamy, who has been emboldened by the institution’s commitment to equity beyond a single curator. “That is very important because you can’t speak about what happened in Australia in the same breath as what happened in India and you definitely can’t do it in the same breath of what’s happening in Europe.”

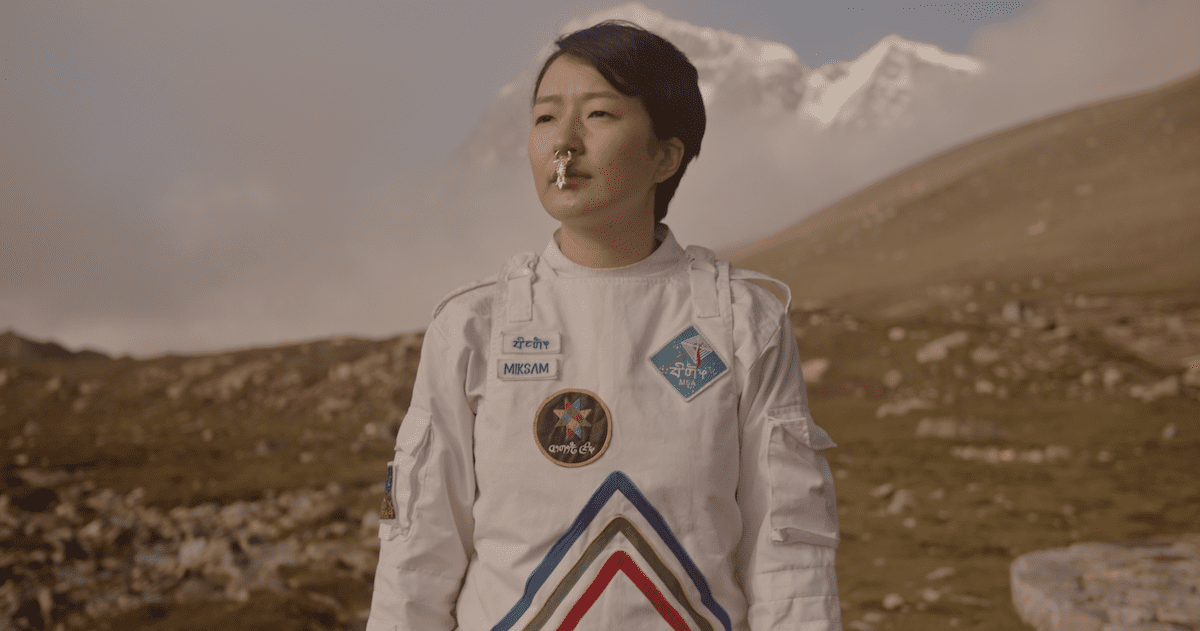

Okkoota, he says, is about bringing multiple narratives in conversation with each other. Nancy Quin Yu’s Glass Armour explores cultural strength and pride. Subash Thebe Limbu’s film Ningwasum examines the plight of the Adavasi community in Nepal and imagines a new kind of Indigenous futurism. Sancintya Mohini Simpson foregrounds the legacy of the women in her family and the buried history of indentured labour via her arresting 2018 video work In Fields of Cane.

“It was the first time I really looked at this history of indenture in my family in such a visible, honest way,” Simpson says. “It’s my life, it’s my mum’s life and it’s our story and it’s part of us. It’s in our bodies. It’s also about indentured labour of women in the Caribbean, in Mauritius, Fiji and about acknowledging the histories here in Australia, with blackbirding.” She pauses. “The women who came before me didn’t have the privilege to tell their story, to be an artist. But they survived. They’re with me and they’re in the work.”

Okkoota

Melbourne Arts House

12—23 April