In Shinto belief, there are countless deities or gods threaded through existence in nature and man-made objects. Such were the early lessons for Kyoko Hashimoto, born in a small seaside town in Shizuoka prefecture near Mount Fuji in central Japan.

Her maternal grandmother would prepare and serve traditional osechi-ryōri dishes each new year, each ingredient imbued with spiritual meaning and renewed wishes for health and abundance.

When she was 11, Hashimoto’s parents, both ceramicists, decided to leave Japan for Australia, her father’s interest in Western cultures piqued first in childhood when attending kindergarten at Tokyo’s American School then as an adult when his best friend wed an Australian.

Yet Shinto philosophy, “stayed with me, that introduction to the world”, says their sculptor, jeweller and painter daughter, now 45, looking back on her foundations from her studio in the Adelaide Hills.

Today, bushland surrounding the studio has proven rich in natural resources for Hashimoto’s latest exhibition, Eight Million Deities. While specificity of place has long marked her works here, collaborating with artist and life partner Guy Keulemans for the past decade, never has the source been so close to home.

Building her reputation as a contemporary jeweller for more than two decades, first earning a Master of Fine Arts at the University of New South Wales, Hashimoto has previously used heavy sculptural materials bespeaking environmental pressures: a necklace made from coal; large prayer beads made of concrete; mirrors wedged in bauxite normally destined for the smelter.

But 2022 brought a turning point: Hashimoto was diagnosed with breast cancer. Emerging from treatment the following year and awarded a Guildhouse Fellowship in partnership with the Art Gallery of South Australia, she decided on a new direction, “to focus on developing a sustainable practice both on the physical body as well as on the environment.”

Her trial and error in foraging began with six months of experimentation in non-toxic materials. First, she gathered eucalyptus as well as acacias, and attempted to make paper. But she found the native flora too dense for her purpose.

“I even made paper from koala skat,” she says. “I thought, ‘Koalas consume just eucalyptus, so they’re doing some of the work for me’, by digesting plant materials. It’s gross, but I wanted to push this experiment.” She used hide (animal) glue as a binder, rather than petrochemicals.

Then her eye turned to the weedy ivy growing across her yard. “That seemed to make sense, perhaps more sustainable using invasive species as opposed to natives,” she says. Hashimoto holds up a sheet of her paper made from ivy, which she arrived at by stripping the thin layer of bark with a small kitchen knife, then steeping the plant in an alkaline solution, followed by pounding it until it became a fibrous pulp.

The paper was then used to make papier-mâché objects: Hashimoto produces a box from which she pulls out one of the larger works for the exhibition made from ivy, a six-metre-long chain. The artist is working with a videographer on a companion film showing the chain draped around a large tree in her yard, a riff on the hemp or rice straw ropes found around trees within Shinto shrines across Japan: a practice that symbolises kami, the presence of spirits or deities.

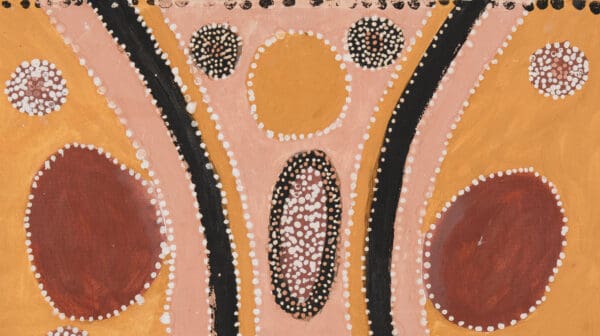

Making pigment became another part of Hashimoto’s evolving practice. She collected various red, yellow and green rocks from her garden and pounded these in a manner not unlike the Indigenous Australian tradition of grinding ochre, rich in iron oxides, for paint. White paint was made from oyster shells bought at a fish market.

Hashimoto then painted a series of abstract works for her exhibition, inspired by the petrographic structure of the rocks, their appearance captured by microscopy after being pressed onto glass at a specialist laboratory in Adelaide. Hashimoto holds up some glass slides of transparent wafer-thin rock slices (0.03 millimetres): “You can see some amazing colours and patterns.”

This move to non-toxic materials is “probably permanent”, she says. “I’ve been a contemporary jeweller for more than 20 years, and I needed an expansion or a shift in my practice; my work was already becoming quite sculptural as opposed to wearable.”

“When I got sick, my previous way was not sustainable, not just in the material sense but for my physical body. “Any art practice has an element of being exposed to toxins, which you can mitigate, but even if you protect your body from toxic fumes, those go into the air, and you’re flushing materials which end up in the ocean. “In the very long run, it does come back into your body. It’s all connected.”

Kyoko Hashimoto: Eight Million Deities (Yaoyorozu no Kami)

Art Gallery of South Australia (Adelaide / Kaurna Country SA)

Until 2 November

This article was originally published in the September/October 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.