Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

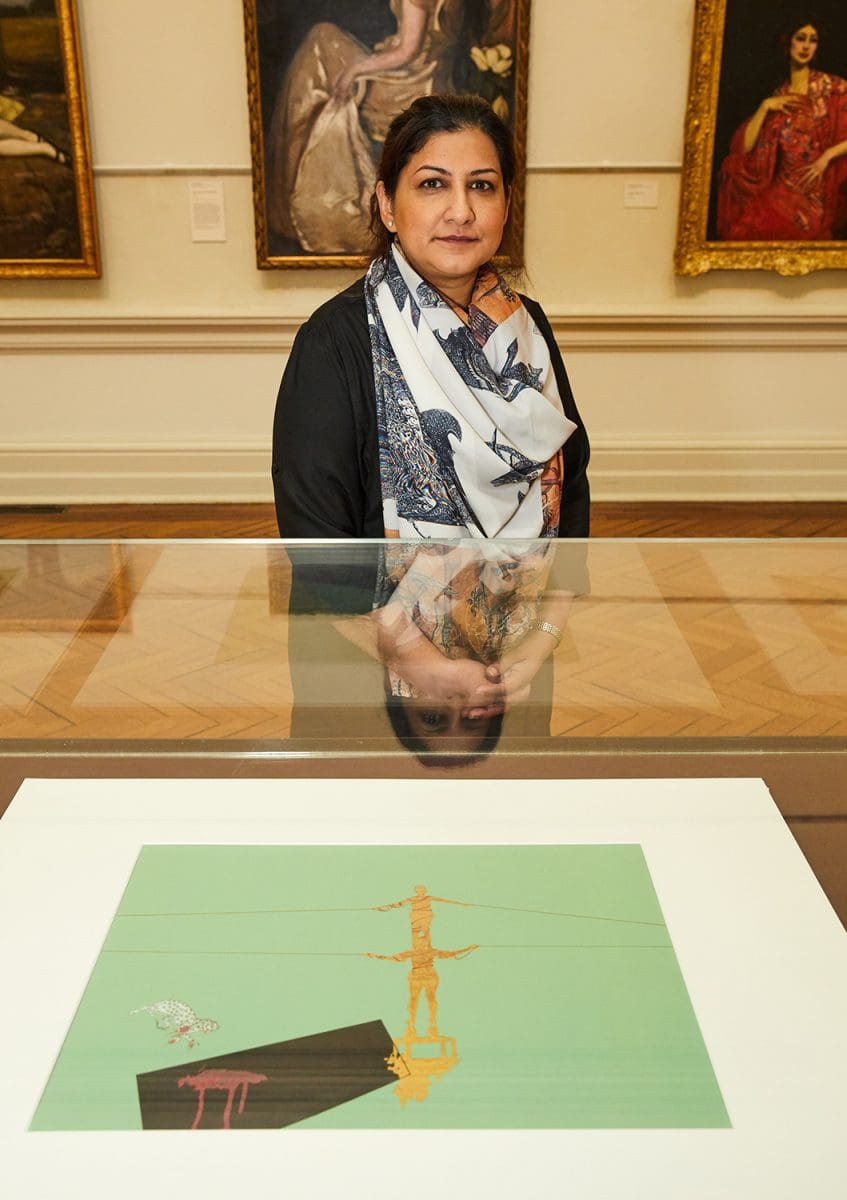

The Lahore-born artist Nusra Latif Qureshi, who has won the 2019 Bulgari Art Award for a selection of six of the paintings she has produced since she arrived in Australia in 2001, says women in Pakistan feel intense pressure to leave the family home once they are of marriageable age.

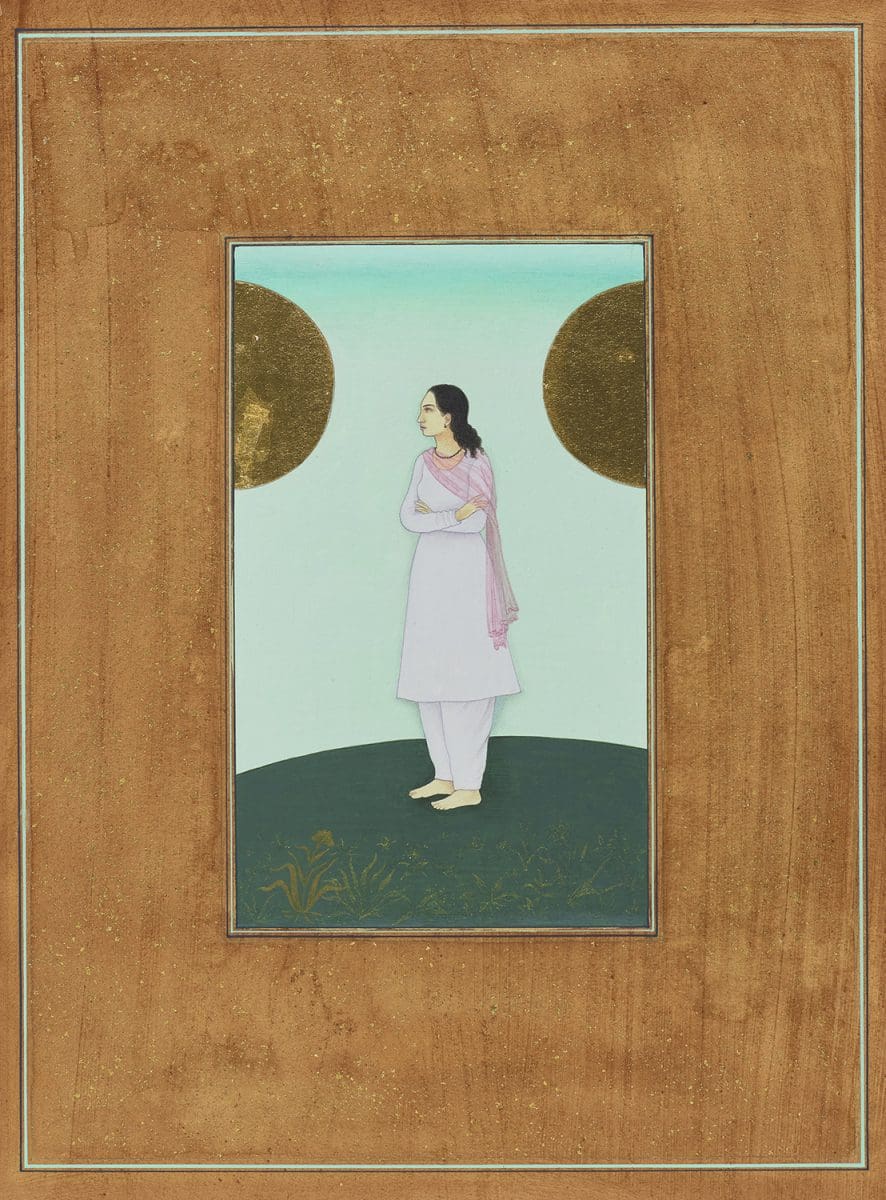

Qureshi has, she says, “battled” such denial of women’s agency in some cultures “quite a lot in my work.” From her Melbourne home, the day after the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) announced her win, she adds, “I do question conventions of a lot of different kinds: historical and political conventions and social ideologies.”

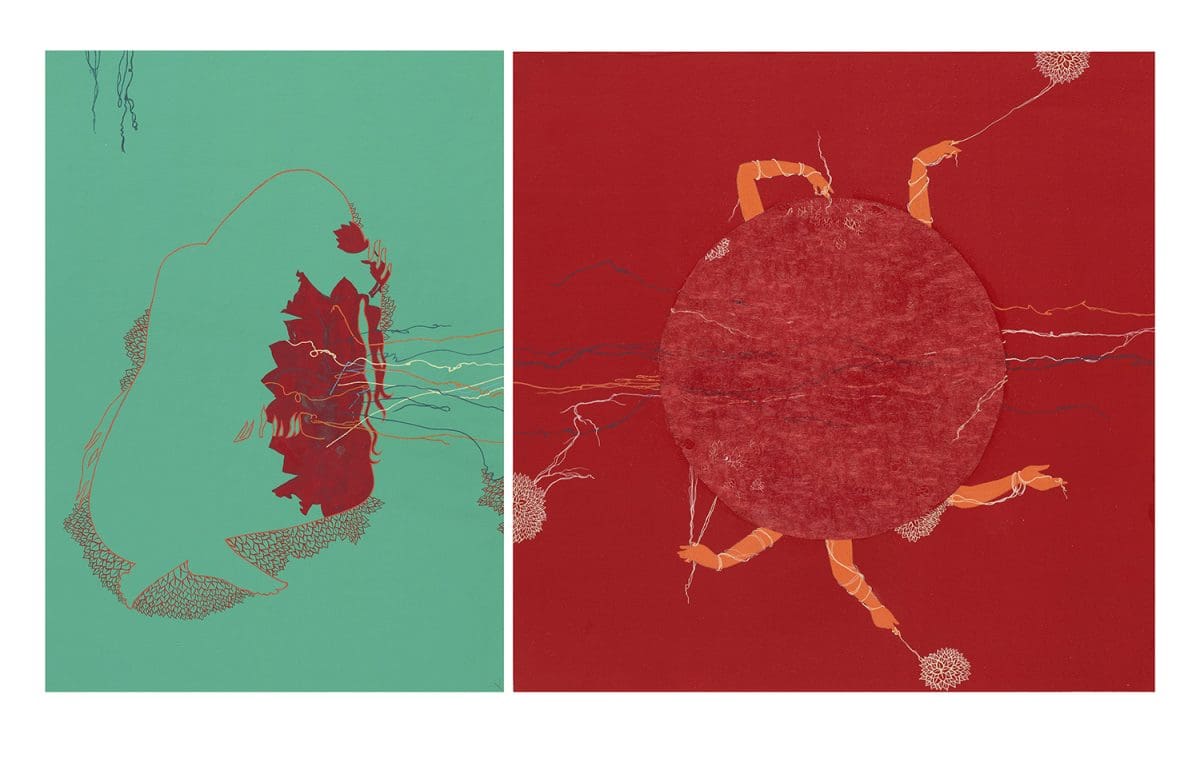

Her artworks often depict “this lonely figure, this young woman who is trying to create an intellectual space and a social space for herself, which she is denied constantly,” she says. “She is supposed to be explained and justified by being married to a man.”

Critiquing the male gaze throughout art history, Qureshi also questions the “absence of a female protagonist and even a point of view in major art collections,” she says. “Historically, there are not enough women’s voices in the art world.”

Her prize (the first time it has been awarded for a suite of work rather than a single painting) includes $50,000 for the AGNSW to acquire the works and $30,000 for her to undertake a study trip to Italy, where Qureshi is free to create her own, as-yet undecided, itinerary.

Born in 1973, Qureshi had a “completely average, working class” upbringing. Her ambition to become an artist was seeded during her high school fine art elective, and she went on to study at the National College of Arts in Lahore, where training was “tough and rigorous” while “extremely rich and terribly professional.”

Students had to learn in about two-and-a-half years the basics of centuries-old techniques, in particular the miniaturist Pahari painting that originated in northern India as well as art styles the Mughal courts had brought from Persia to the south-east Asian region some 500 years ago.

Wayne Tunnicliffe, the head curator of Australian art at the AGNSW, says Qureshi’s work shows “how the past can affect the agency we have in our lives today.”

Qureshi has returned often to Pakistan since leaving in 2001, witnessing the growth of its consumer market. “The branding of individuals is quite rapidly in progress there. Not exactly Americanisation, but this drive to feel entitled to be wearing brands, to be looking like a certain individual who owns such-and-such phone, who drives such-and-such car, who eats in these branded places; you have to eat McDonalds now, you have to be seen eating KFC.”

Branded consumerism “can be quite annoying, and the death-knell for traditional practices,” she says. So will Qureshi deal with this phenomenon, which she has been studying, in her art? “Sometimes it takes many years for something to mature into a comprehensive or even legible argument,” she explains, “to be sophisticated enough to be shared with other people.”

Would Qureshi’s artistic career have fulfilled its promise had she stayed in Pakistan? “Definitely,” she says. “The cultural context there is extremely enriching and rewarding in its own way; there is access to techniques and materials and craftspeople: there’s an analogy to how many contemporary Chinese international artists are working … It’s an extremely interesting option, though I did not choose to stay there.”