Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

It is hard to think of a contemporary artist that uses the past to envision the future quite as thrillingly as Wangechi Mutu. Last year, the Kenyan-American sculptor became the first artist in 117 years to create work for the façade of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her sculptures, The NewOnes, will free Us took the form of four bronze caryatids, the female statues that have doubled as pillars since antiquity.

Mutu’s figures, shrouded in coils and crowned with smooth discs, resembled cosmic messengers from another moment. Her sculptures were exempt from the labour of holding up buildings, free from the weight of history. Last year, she told the Financial Times: “I wanted them to sit upright and still and unencumbered and unafraid.”

Mutu rose to fame in the 1990s, with freewheeling collages of goddesses and cyborgs, intricate paintings of Black female bodies that levitate mid-air, alive to their own desires. Her work has long explored elements of Afrofuturism, an aesthetic that, as the critic Mark Dery puts it in his 1993 essay Black to the Future, evokes a “speculative fiction [that] addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth- century technoculture.”

You can find the influence of Afrofuturism in the experimental jazz of Sun Ra, an avant-garde composer who was working in the 1960s, and the Black utopias of sci-fi writer Octavia Butler. It manifests more recently in the work of Nick Cave, whose technicolour Soundsuit series grapples with the trauma of the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Then there’s Arthur Jafa. The artist’s virtuosic video work Love is the Message, the Message is Death features a giant blazing sun that rises and falls over scenes of people dancing, the promise that new days can remake old pain, turn suffering into something transcendent.

Although Afrofuturism speaks to the specifics of the Black experience, its ability to imagine a future free of oppressive structures has wider resonance, finding common ground in different histories of struggle and liberation.

For instance, Richard Bell’s work titled Embassy, an installation that was first shown in Melbourne in 2013 before touring to Moscow, New York and Jerusalem, has carved out space to describe a country unburdened by colonial hierarchies. It has also sparked a spirit of solidarity between a legacy of Indigenous activism and movements such as Black Lives Matter.

Bell’s work is one of the many ways that contemporary artists are creating structures and languages to articulate a reality that doesn’t exist yet, galvanised by a global pandemic and ecological crises to boldly imagine other worlds.

Performance and video artist Hannah Brontë believes that it is the responsibility of artists to reflect the times they live in.

It is an era, Brontë says, defined by “the spread of a respiratory virus and the death of George Floyd [whose] last words [were] ‘I can’t breathe,’ the same words shared by David Dungay Junior, five years earlier, only recently acknowledged by the wider ‘Australian’ public.”

She says, “the feeling of being restricted by the government has been the case since colonisation.” But Brontë, a Wakka Wakka and Yaegel woman, doesn’t just grapple with the long shadow of colonial dispossession in this place we call Australia. She draws on the vocabulary of hip-hop and protest as well as the matriarchal lineage that is part of her story to create utopian alternatives that can coexist alongside our current world.

Since 2016, the artist has been hosting Fempre$$, a series of dance parties that combine live hip-hop, performance and visuals. She says that her club nights, which have toured around the country, centre queer, Indigenous, Black, brown and Pasifika women.

“The envisioning of these realities, if only for a night, is [like] a portal into a dreamscape,” she says.

In HEALA, a video installation shown at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art as part of The National, a group of women—one pregnant—dance together in the ocean to the rhythm of gentle rapping. The work, enshrouded in an orange curtain, links the destruction of nature with violence against women. But it was also conceived as a release for ‘womb grief’, a place to release the trauma Indigenous women can hold in their bodies.

“This work was for my sisters who passed and my sisters who thought about leaving,” she says. “My darlings got out of their painful seas and are laying on beaches, calm in the sun. I imagined swimming in their pain, drumming it out of their bodies. I wanted to create a place for them, even just within an artwork.”

Léuli Eshrāghi is equally invested in bodily pleasure. The Sāmoan, Persian and Cantonese artist and curator believes that achieving freedom in the future is about looking closely at history. For Eshrāghi, who uses the Sāmoan pronoun ‘ia’, this means wrestling with the legacy of Western missionaries in Sāmoa, who replaced more fluid ideas around gender, sexuality and kinship with cultural taboos.

“It’s about seeking to undo the embodied shame that comes from the church, from a monotheistic outlook,” ia explains. “[For thousands of years], there were different kinds of relationships with mountains and rivers, non-human beings and presences.”

These ideas coalesce in Eshrāghi’s installation titled re(cul)naissance, French for ‘stepping back’. The work takes the form of an eight-limbed deity, conceived as shimmering swatches of fabric that hover over a pool of water, awash in the glow of pink neon. This “ceremonial framework”, as Eshrāghi describes it, features a video that stars friends of the artist.

“In the video, my friends from Fiji and Western Samoa are trying to imagine, in our bodies, what it would be like not to feel shame around desire,” ia says. “I really link a future state of wellness and a previous state of wellness with sensuality and pleasure and the pleasure of hearing [and seeing] visual language.”

Eshrāghi says that Indigenous Futurisms are also about liberating cultural memory from colonial forms of knowledge. As part of AOAULI, an upcoming digital commission for the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art’s online project ACCA Open, the artist will present siapo viliata (translating to ‘moving bark-cloths’)—animated versions of traditional siapo, Sāmoan mulberry-bark cloths, that ‘travel’ from 2025 to 2020.

“I want to have a positive and generative and truthful look at history, and map what is lost and what is gained,” ia explains.

Alicia Frankovich, too, is thinking about a future that is free from Enlightenment ways of knowing and understanding ourselves. “I’m working on an Atlas of Anti-Taxonomies that draws on the question of what is a body and looks into all sorts of bodies—including the non-human,” says Frankovich, a New Zealandborn artist whose work spans installation, video and choreography.

“I’ve been [reading Māori scholar] Linda Tuhiwai Smith recently. Decentring the human and acknowledging the land and its stories is not a new concept.”

For Frankovich, these ideas became urgent in the wake of the summer bushfire crisis, when she was forced to leave Canberra for Melbourne with her partner and new baby. A new piece, based on this experience, will show at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in October.

“It’s going to have a smoke machine inside a booth,” she says. “My work has become more dystopic than it was before—there is this tussle between utopia and dystopia.”

Our dystopian present is also front of mind for performance and sound artist Archie Barry. “The current lockdowns are [a] societal obligation that [result] in our nervous systems being exposed to an increasingly narrow bandwidth of experience,” they explain. “When our senses are standardised, we lose our capacity for imagination.”

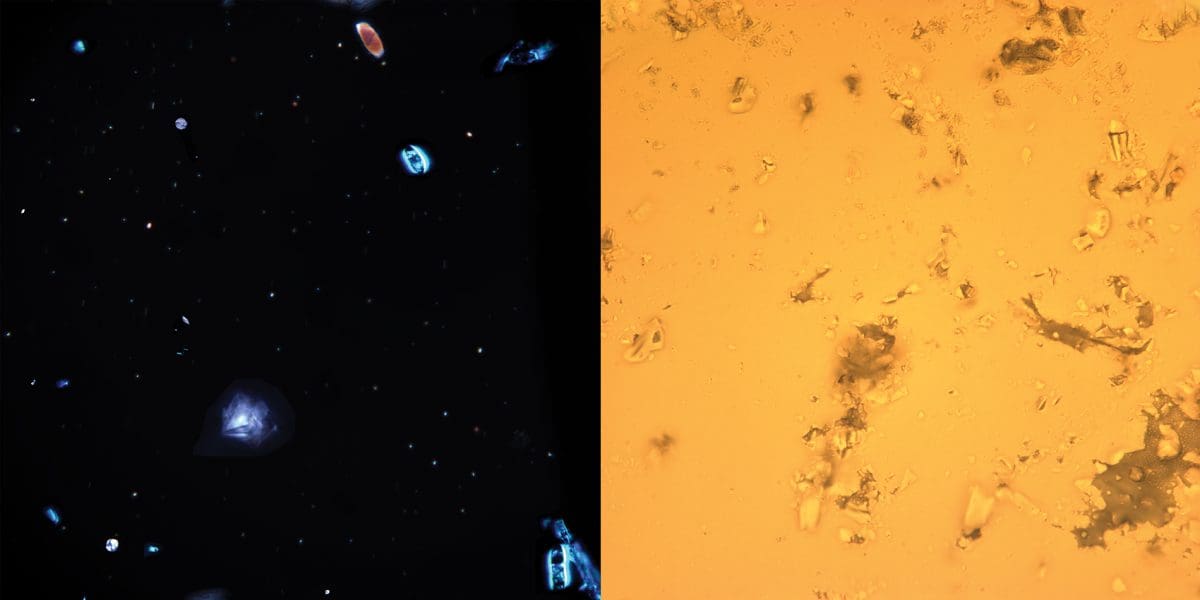

Barry’s new work, also part of ACCA Open commissions, is tentatively titled Multiply. It takes the form of a soundtrack, based on sense impressions collected by the artist. “The pathogen is one of a number of voices,” they say.

Barry hopes it will create new ways of thinking about this moment. “[Multiply] is an invitation to grief and multiplicity, which can nurture our ability to meet the conditions we are living through,” they explain. “Developing the soundtrack has felt a bit like writing a screenplay for a film that doesn’t exist.”

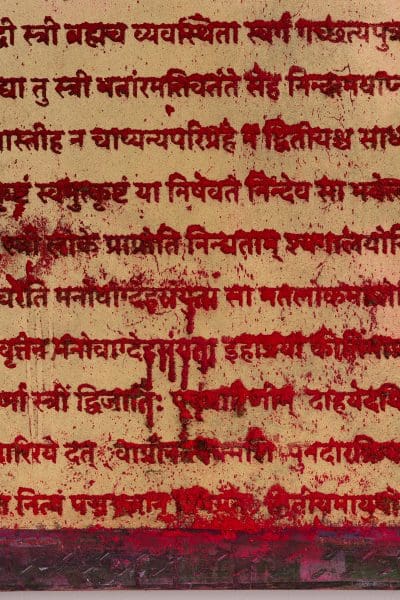

Contemporary art about the future—Wutu’s statues, Cave’s Soundsuit series—is speculative by nature. At its best, it blends fantasy and reality to imagine radical possibilities for living, creating blueprints for liberation. Kirtika Kain, a Delhi-born, Sydney-based artist, examines what it means to be Dalit. She is part of the 300 million-strong community that has been, for thousands of years, deemed ‘untouchable’: the bottom of India’s oppressive caste hierarchy, forced to carry out the most degrading tasks in society.

For Kain, who was raised on Sydney’s Northern Beaches, envisioning the future isn’t yet about looking forward. It is a process of ‘settling into’, of sitting with the embodiment of her own history, allowing herself to feel it in her bones and skin.

Corpus, Kain’s first solo show last July at Sydney’s Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, saw the artist embrace the unseen elements of Dalit material culture—iron and wax, broom twigs and human hair.

“Corpus was about finding the politics that exist within one’s own body,” she says. “We are all political bodies, whether we are privileged or not, and to find all of this discourse back within ourselves is the true transformation, whether we are the perpetrator or the victim.”

Kain’s upcoming show at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Stone Idols, draws on The Prisons We Broke, an autobiography written by a Dalit woman called Baby Kamble. Kain hopes to give the experiences described in the text a material expression. For the artist, creating the future is about making space for lives the world still hasn’t witnessed.

“I imagine a future where caste doesn’t exist but it’s not about forgetting,” she smiles. “Dalit history and brutality hasn’t even been seen yet, how is it going to be healed? What our ancestors and forefathers have paved for us will be carried by us. I feel like my practice is my way of contributing to my community, to create and claim a space for it.”

AFFIRMATIONS DURING THE Apocalypse

Hannah Brontë

Making Art Work: Institute of Modern Art x Brisbane Festival

7 September—21 September

ACCA Open: AOAULI

Léuli Eshrāghi

ACCA online

From 30 September

ACCA Open: Multiply

Archie Barry

ACCA online

From 30 September

Stone Idols

Kirtika Kain

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery

Dates to be advised

This article was originally published in the September/October 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.