Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

What do horses dream of? Coinciding with the Melbourne Spring Racing Carnival, Noel McKenna’s exhibition The Curragh was all about horses and their training. Equally, though, it was about the interior life of the unknowable other.

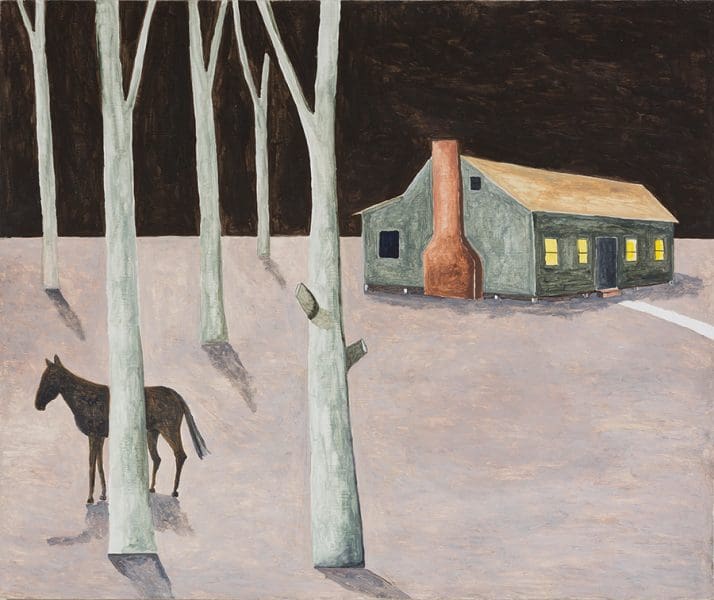

Working in his signature, deceptively folksy (but really rather sophisticated) style, McKenna created a baker’s dozen of mostly medium-sized paintings of horses in barns and paddocks, on racetracks and pathways. In an introduction in the exhibition catalogue, McKenna spoke of going to the races with his father as a child in Brisbane and, more recently, visiting a famous and venerable racetrack, The Curragh, during a trip to Ireland, where his family has Catholic roots. While the exhibition doesn’t include scenes from The Curragh, his trip there informed all of the works.

To my mind, the exhibition, held at McKenna’s Melbourne gallery Niagara Galleries, consisted of two subtly different types of paintings. Of course, these categories weren’t hard and fast – there was a certain amount of crossover – but the distinction seems generally useful. (Outside of the paintings there was also a single lithograph, as well as a number of ceramic tiles that gallery staff said weren’t part of the exhibition.)

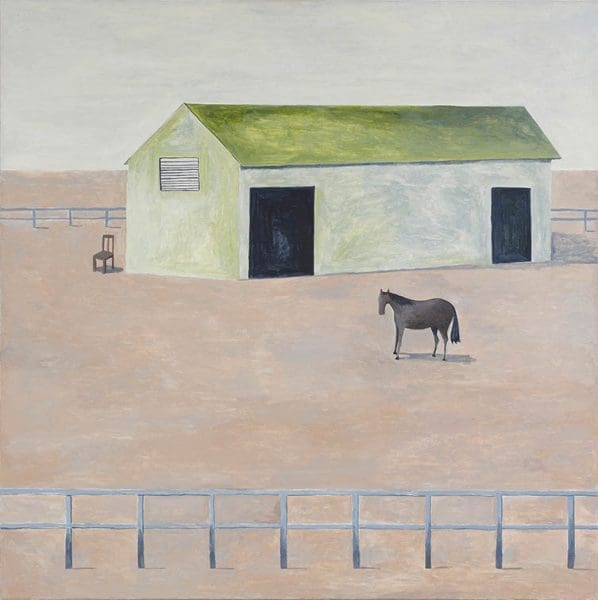

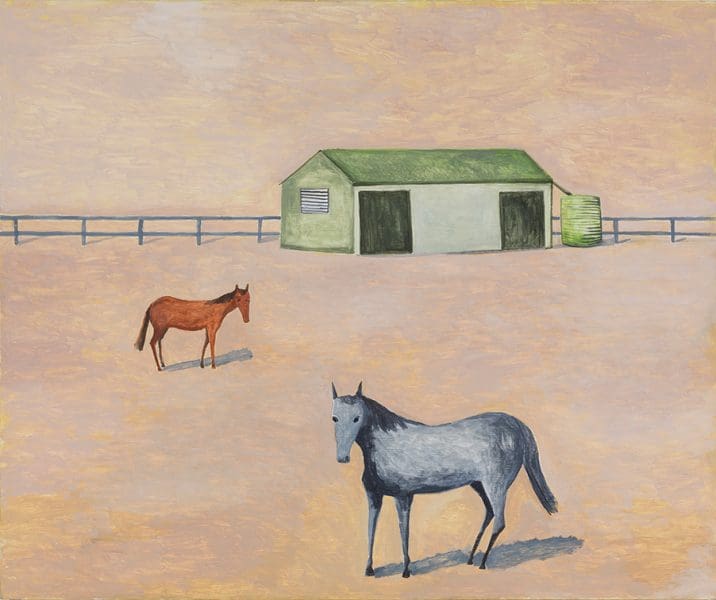

The first group of paintings was based on documentary observation. While not directly showing McKenna’s visit to The Curragh, these images contained specific details that, in the artist’s characteristically spare manner, conveyed an abundance of information about the often-difficult lives of trained thoroughbreds.

In his catalogue essay, McKenna notes that racehorses in particular are social animals that are forced to spend most of their lives alone.

About to be led onto track, 2015 (as for all works), showed a strapper leading a mounted horse and jockey into the black maw of a racetrack edifice. Though the title suggests the horse will soon emerge onto the sunlight of the track, McKenna’s off-centre composition – the dark, looming entranceway off to the right and bottom – depicted the three figures from behind and at something of a distance. Rather than pre-race anticipation we sense a finality, an air of melancholy and hardship.

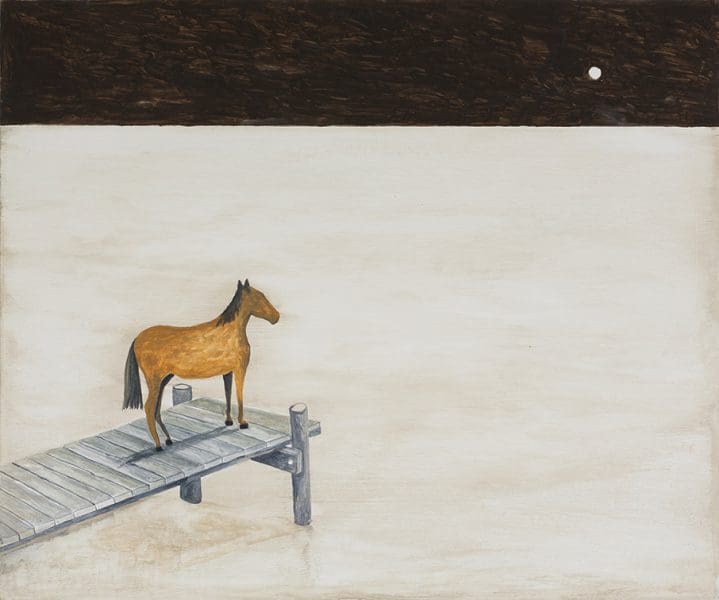

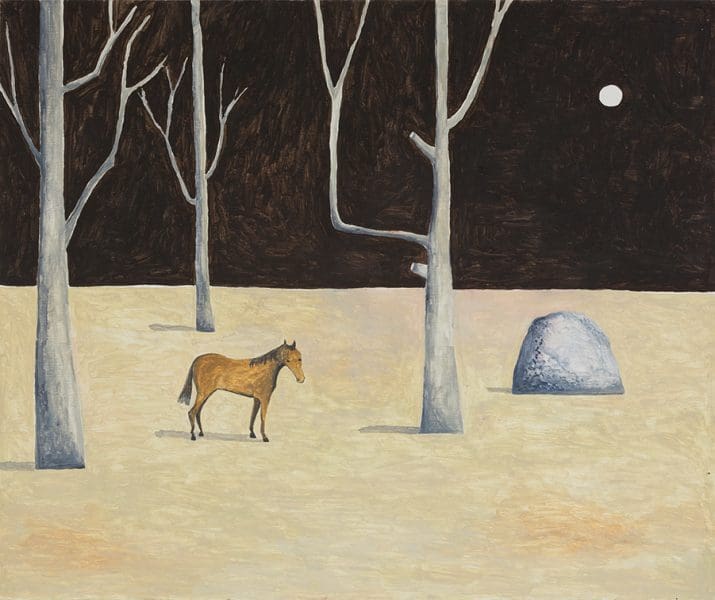

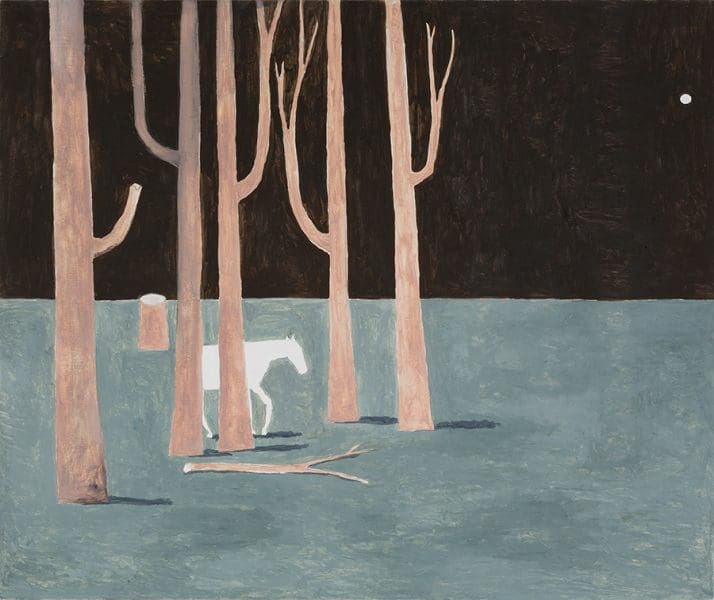

The other grouping of paintings worked more openly with themes of allegory and anthropomorphic emotion. Horses have, of course, always provided a blank screen for these kinds of projections. Not by accident, in these images the horses appeared without human companions, leaving viewers to ponder their inner thoughts. “There is a lot going on in a horse’s head that we do not know or understand,” McKenna writes, “and in this group of works I have tried to maybe say something about the thoughts a horse may have.”

In Horse on jetty a horse had wandered to the end of a pier to look up at the moon, a little dot in a black sky above a luminous, latte-brown sea. Existential horse. With its anatomically not-quite-right two eyes looking towards the viewer, Lost horse looked simultaneously dumbstruck and plaintive, while White horse – a nightscape with a silhouetted horse (with single unblinking eye) amid a sparse forest – was more likely to evoke plain sadness. Even while working with minimal representational detail McKenna has the ability to convey finessed shades of emotion, such as the differences between plaintiveness and sadness.

The appeal of McKenna’s work lies partly in its disregard for belaboured painterly technique. He pares images down as if whittling, while amplifying their emotional resonance; in this way, he cuts to the quick of anything worth representing. He’s not afraid to use almost cartoonish conventions – the flat two-eyed face in profile, for example – in order to distil the essence of a picture’s meaning. Horses, as readymades for psychological projection, seem like an obvious choice then for McKenna. In fact, the interior lives of animals, not to mention depictions of horses, have been constant features of McKenna’s almost-40-year career. Given his familial associations with being around horses – he says he still occasionally goes to the races – this suite of works was a natural fit, showing an artist comfortable in the saddle.

The Curragh

Niagara Galleries

20 October – 14 November 2015