Family Ties

Using the powerful connection between mother and daughter, Generational at Madeline Gordon Gallery in Launceston, explores this intimate relationship with creativity and complexity.

The collegiate artists’ discussion, critical and wholehearted, is a productive and deeply rewarding activity. Together, Consuelo Cavaniglia, Ellen Dahl, Yvette Hamilton, Taloi Havini and Salote Tawale have harnessed peer discussion as the platform for an exhibition. Their prolonged, speculative conversation about islands, personal history and geographical imagination takes form in Vanishing Point, an exhibition of new photomedia work. This is the group’s second exhibition, having recruited Havini and Tawale after their first outing at Perth Centre for Photography in 2016.

“This is an artist-led project,” says Sydney-based artist Consuelo Cavaniglia. “Ellen [Dahl] wanted to talk to somebody about islands. We were drawn together and the discussion stretched out. It’s distinct from working alone or with a curator. It’s not quite collaboration either. It’s an extended conversation among women. Women are writing the essay and giving the opening speech.”

Their place in a more metaphorical horizon is embedded in tropes like wilderness and remoteness. They are precarious too; falling within tidal zones, flood risk areas and within fatal reach of swelling sea levels. That they may be so many things ensured a breadth that could accommodate five artistic approaches.

Dahl’s black and white photographs manifest this complexity. Each is a portrait of an island, both figuratively and symbolically. Some depict the wilds of Tasmania, others Magerøya, the remote Norwegian island where Dahl grew up. The artist draws a complicated view of islands as drastically diverse and yet also sharing something in common – a magnetic quality.

Contradictory language flecks the artists’ explanations of Vanishing Point. Phrases like push and pull or isolation and proximity mark out its poetic territory. “This arose from our focus on impulses rather than specific instances,” explains Cavaniglia. Vanishing Point rests

not on geographical sites, but on the intangible spectres islands produce: feelings of belonging, memories, mirages and myths. That the exhibition centres on photography compounds this transcendence from land to lyricism – “Photography allows you to reach across distance; see but not touch,” says Cavaniglia.

Photographic slides retrieved from her late father’s collection are translated into enormous, high-resolution prints. They evoke Havini’s home island of Bougainville, from the encompassing sea, to its spawning coral reefs. Yet our view is at a remove – filtered through a father’s eyes, his camera lens, passing time and an encrustation of dust, scratches, mould and discolouration that clings to the ageing slides.

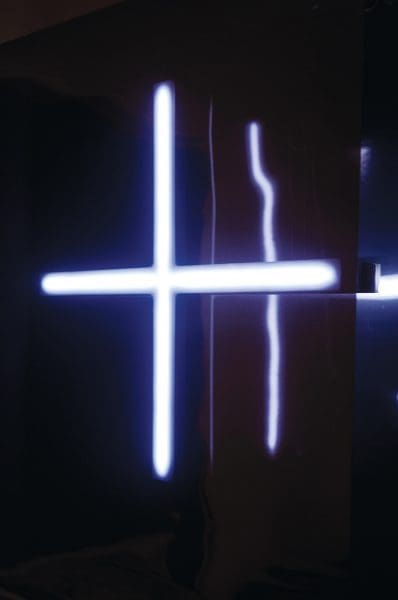

Though Vanishing Point is nominally a photography exhibition, the artists deal more in what is photographic. With towering printed paper draped from wall to floor Cavaniglia blends photography with installation. Her untitled series seems to depict a horizon line, sunset colours and sweeping proportions. Yet this impression is fleeting. “You get the idea of sky and ground, but they’re inverted,” says Cavaniglia. “You can’t locate yourself within it.” Yvette Hamilton’s islands are similarly slippery. The artist is half Mauritian, dreaming always of her heritage. Her installation Phantom Island draws on this personal history. Through porthole-like apertures, islands are revealed then disappear, leaving one staring at one’s own reflection.

A video in which her face flickers into many different poses “suggests that many people make up who she is,” says Cavaniglia. Representations of traditional Fijian vessels alongside cans of Coca-Cola provide a complex picture of isolation – island life is contrasted with the Melbourne suburbs she grew up in, where there was “no Fijian presence at all”. Across the exhibition, autobiography is embedded within every description of what islands can be.

The enticement to continue is hurried by the changing fate of islands themselves, as they are engulfed by water and become more accessible, owned and known. “People are even trying to make new islands by creating borders, drawing lines and stopping migration,” says Dahl. This development, adds Cavaniglia, is underpinned by the notion that an island’s isolation gives it some purity. “In Australia there is this idea about contamination, politically and environmentally. The distance of an island, its apartness, is valuable.” As real islands and the romance of imagined ones fades, others are rising, says Dahl. “You could call it islandification,” she says. “People are seeking it.”

Vanishing Point

Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre

21 April – 11 June