Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

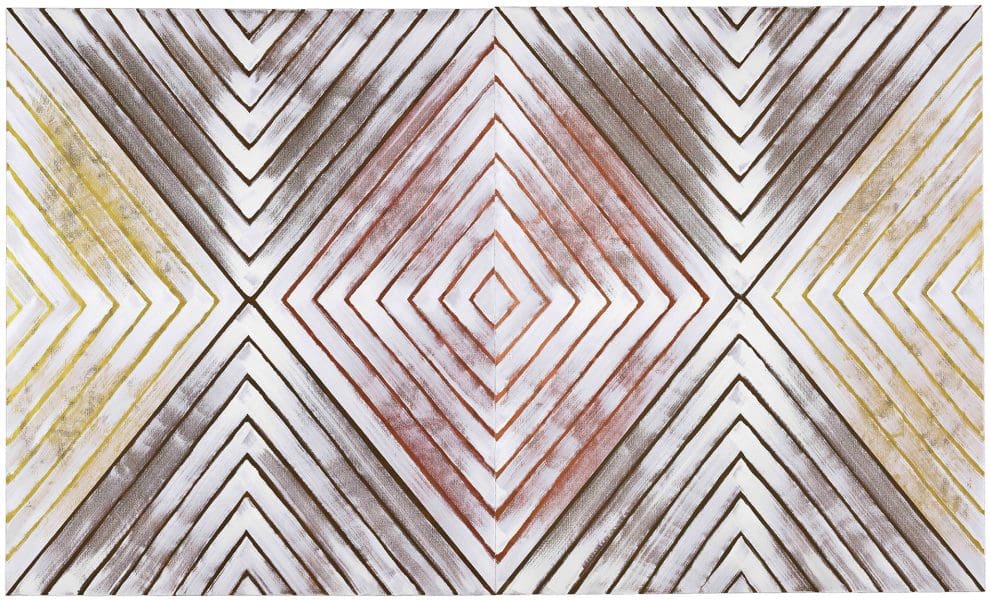

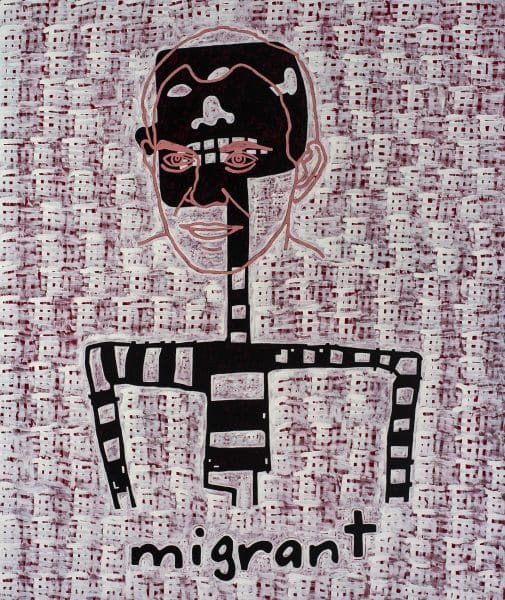

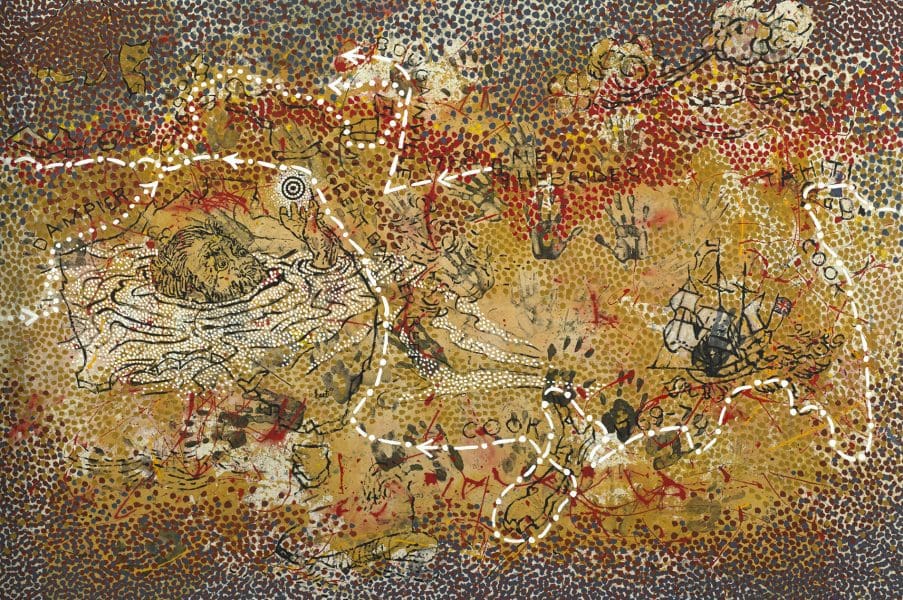

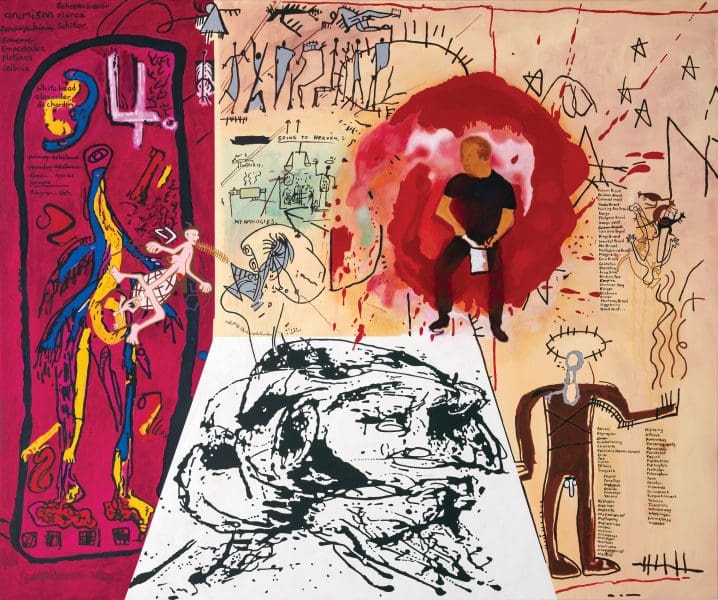

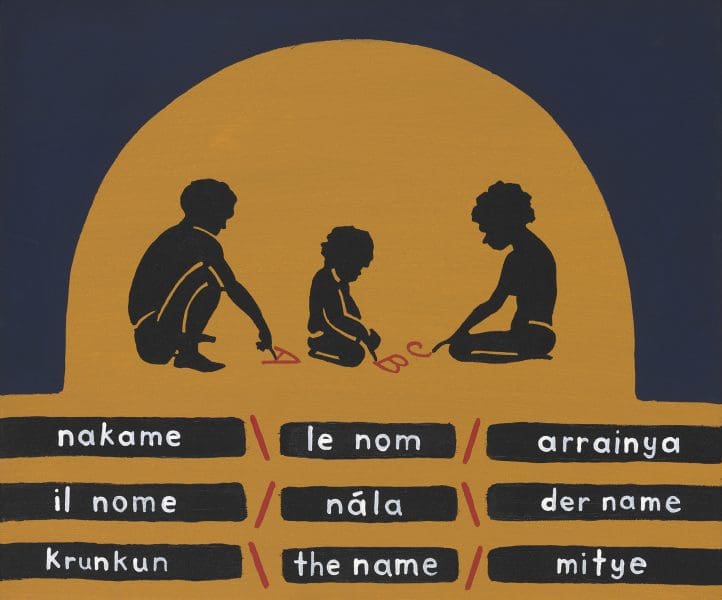

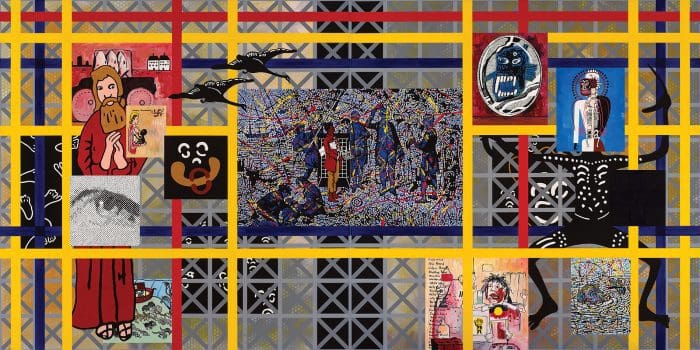

Queensland-born Gordon Bennett was an artist who loved collapsing ‘high’ and ‘low’ art boundaries. From early on in his successful career, curtailed by his death in 2014 at age 58, he was well-known for disrupting the status quo with his unique visual language. He probed ideas about identity, fuelled partly by his own Indigenous heritage, and stared unflinchingly at race, history, self and truth, insistently leaving his work open to interpretation.When he died, Bennett had finished with one series of works and was yet to explore another, so there were not many incomplete pieces in his studio. Even so, Zara Stanhope, the curatorial manager of Asian and Pacific Art at Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), has named the new large-scale show of Bennett’s work Unfinished Business. As she observes, Bennett was always deeply engaged with the world, and there remained much for him to do.

Stanhope has co-curated the show with Abigail Bernal, assistant curator of international art, and it is the biggest exhibition to focus on Bennett since 2007. It features about 200 works, including major works and series, and others shown either rarely or not at all.

Stanhope and Bernal were given open access to Bennett’s studio, in a building behind the Bennett family home in Brisbane. There, they worked through the oeuvre of an extraordinary man, an artist with a global reputation who was always able to surprise and engage visitors—but not give them easy answers or clear readings.

“I wanted Gordon Bennett’s work to speak for itself rather than layer it with interpretations,” Stanhope says. “I felt it was important to show how he worked in series, so people can understand how he would process ideas through a number of connected works.” His repeated topics included grappling with how to open people’s eyes to discriminatory practices were deaths in custody and the refugee situation. “He was so aware of those things and he felt so ashamed about them in our society,” Stanhope says. “His work is quite insistent—but it can be humorous and beautiful at the same time.”

A highlight of the exhibition, organised mostly chronologically, are Bennett’s works on paper, many of which have not been publicly viewed. His practice covered painting, installation, sculptural assemblage, video and ceramics, but Stanhope has been fascinated by the drawings which sometimes depict imagery that was further developed in finished works. “You can see the artist’s hand at work,” she says. “They are a bit quirky and you get a strong sense of Gordon himself.”

Bennett was about 11 when his Aboriginal heritage dawned on him—his mother, it turned out, was a Birri Gubba/Darambal woman and spent her childhood in Cherbourg Aboriginal mission. But his parents would not speak of this and he was raised as an Anglo/European. In the exhibition catalogue, Bennett is quoted as saying that by the time he entered the workforce, aged 16, he learnt “how low the general opinion” of Aboriginal people was. “As a shy and inarticulate teenager my response to these derogatory opinions was silence, self-loathing and denial of my heritage.”

But when he later went to art college, aged 30, he explored this with enormous passion and fearlessness as he acknowledged and embraced his dual identity. “It all came pouring out at art school,” Stanhope says. “He had been going to a psychotherapist and reading a lot of psychology and wanted to make some art as a result. It was all bottled up in there. You can see how he was expressing himself through image-making.”

This, she says, very quickly formed into the finer practice we now know and have seen develop. Equally formative was his exposure to postmodernism and French structuralism, and thinking about how to create his art in that context. He went on to relentlessly explore appropriation, the weight of art history, expression of identity and the effects of the conscious and unconscious on collective and individual psyches. Being awarded the Moët & Chandon Australian Art Fellowship, resulting in a year’s residency in France during 1991-92, was pivotal. Stanhope says the painting that won him the fellowship—The nine ricochets (Fall down black fella, Jump up white fella)—is rich with such layering.

Bennett was well-known for avoiding interviews; there is little evidence of him in the exhibition displaying a public face. “We wanted to make sure we held to the integrity of the work and allow his voice to come through,” Stanhope says. “It is a show where you can spend a lot of time and see the variety in his work: you can look at a series but then also look at the connections between the series.”

Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

7 November 2020—21 March

This article was originally published in the January/February 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.