In Anchor: A Prelude (2018), artist-curator and filmmaker Nikki Lam’s three-and-a-half-minute video installation, we are treated to shots of nature with text at the bottom of the screen, the background regularly overlaid by various smaller diametrical images. A garbled drowning sound gives way to rain and birdsong, transitioning to a children’s tune. There’s no speaking. At the one-minute mark, a black rectangle overlays an image of a rocky beach, then is swiftly removed to reveal the entrance to a Shinto temple. Two different photographs of a look-out spot similarly lap the same entrance in succession, until the screen is suddenly blanketed by a lurid red. The text at the bottom reads: “Can memory be colonised?” Here, we enter the second chapter of the video, where elements repeat and further queries surrounding history and memory are ventured.

As a city-state with a multilayered past and present, shaped by Britain post-Treaty of Nanjing and then “returned” to the People’s Republic of China in 1997 through a “handover ceremony”, Hong Kong exists at the now-unambiguous nexus of Western and Chinese imperialism. Its identity is constantly shifting, a manufactured urban zone built upon the capitalist extraction of its residents as it bends with global economic tides. Influential neoliberal economist Milton Friedman once called it his favourite “example” of a place where capitalist freedom could be attained by sacrificing political freedoms. It results in what Lam describes to me as “contested, state-informed histories, [which makes it] challenging to find lineage within a conventional ‘archive’.”

Lam was born and raised in Hong Kong before leaving for high school in regional Victoria at 16, subsequently studying art at university in Melbourne. Migrants who move countries solo post-adolescence generally feel more dissociated than their second-generation diasporic counterparts, who typically have their families alongside them. A double-edged haunting lingers: “I got used to navigating the alienating systems and bureaucracy for over a decade as a young adult [and international student], which shaped how I saw myself in relation to Australia,” Lam explains. “It’s hard to look away when you clearly see a system’s faultlines; you start to notice them everywhere. I think I’m still negotiating this experience every day.”

Since Silence II (2009), her earliest work, a three-channel video installed on floating Perspex, followed by Falling Leaf Returns to its Roots 落葉歸根 (2014), her creative practice has been video-centric and interdisciplinary, including writing and forays into interactive code-based experiential pieces. For 20 years, her late mother worked at a video store that turned into a distributor of art-house films. Consequently, Lam had access to “all kinds of films” she had “no idea [what they were] about until later in life,” such as Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003) and Mizayaki’s filmography. But her mother forbade her to study it, saying that she “knew the film industry”. “I think I have been working my way back to my first passion ever since,” Lam tells me. Her body of work thus far circles specific, enduring preoccupations—cultural histories, postcolonial conditions, dichotomies and memory—from multifarious and non-linear angles. As she once noted in a 2018 interview, Hong Kong’s identity “as a space without location with only fragments of movements over stretches of time […] sums up how I feel about my own hybrid identity.”

In 2023, among five other emerging artists and curated by Talia Smith, Lam participated in Primavera, a long-running showcase of work by cutting-edge artists under 35 living and working in Australia, annually exhibited at the MCA in Sydney. There, she showed the first chapter of a trilogy, the unshakeable destiny_2101, a six-minute film with fellow HK-born, Melbourne-based collaborator and theatre-maker Felix Ching Ching Ho, who features in moody scenes reminiscent of those by Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai. When there’s finally a human voice, we’re enveloped by a thunderous crash as the film reaches its end.

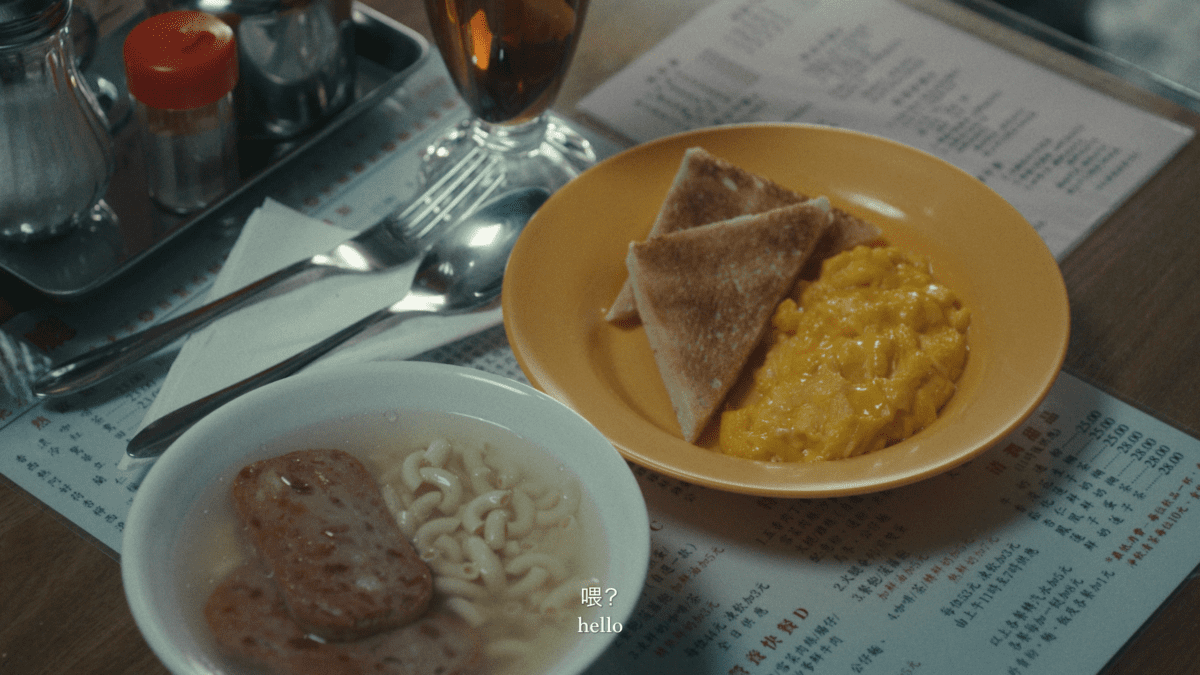

Shot on 16mm, Super 8 and digital and premiering at the Sydney Film Festival in June, The Unshakeable Destiny trilogy was made to coincide with Lam’s doctorate on moving images within the Hong Kong diaspora, which she started in late-2020. Speaking about that period between 2019 and 2021, when Hong Kong once again faced increased repression due to political pressure from the CCP, she felt “perplexed by the situation […] and was trying to find ways to witness or document the aftermath.” After _2101 came Reprise and Retrograde, the final part of the trilogy itself sliced into three parts. In Reprise, we witness someone going about what ostensibly looks like a day in her life until she is faced by another person who speaks desperately at her while she looks on in quiet agitation. In Retrograde, Lam herself appears with the above-mentioned Ho—the two chat about Lam’s processes and ruminations as they move through different locations in Hong Kong. It’s somewhat evocative of Steve Coogan’s The Trip, where he dines at picturesque southern European restaurants while bantering with his friend and co-performer Rob Brydon. Eventually what feels convivial reveals an implicit tension, their interpersonal dynamics coming to the fore as the film develops. But there’s a pointed mournfulness in Lam’s Retrograde, even if there are playful moments; settings were chosen because, as she conveys, “they were what represented my political relationship to Hong Kong.” Meanwhile, she was also trying to evade the trap of explication: “I was trying to peel off nostalgia [for the old country] as the films progressed […] [with] information of the past digested, residues co-existing with the present—all turning towards the self rather than against it.”

The trilogy can be regarded as a feature in itself, its essayistic form derived from Lam’s interest “in the narrative as a form, than as an expression.” What ultimately unites the three chapters is how time co-exists: past, present and future seemingly merge and splinter. Certain lines and metaphors recur, which Lam says echoes “the simultaneous creating and breaking of cycles of repetition, [which is] perhaps part of the migrant experience as well.”

For someone like Lam however, from a city nestled within what scholars have described as (neo)liberal authoritarianism, a feature now much more evident across the world stage, it’s concurrently visage and home. This particular psychic disposition conjures contradictory feelings of suspicion and fondness, both of which are accentuated and pushed upon by the inevitable hyphenated identity as a settler-migrant. Lam mentions that some scenes in Retrograde were challenging as a result—its post-production took a year and a half to complete. Furthermore, “the migrant instinct to conceal is still strong 20 years later.” But it was due to being surrounded by a team who could relate to her specific feelings of dislocation, “and the fact that I filmed the final chapter in my home,” that allowed for her to really lean into the myriad layers, its form peeling apart, onion-like, as it concludes. The Unshakeable Destiny—named after part of a speech by Hong Kong’s 28th and final British governor Chris Patten during the 1997 Handover, and what Lam deems “colonial-speak” impossible to translate into Chinese—ends up both caving to and intervening with engineered histories. As Lam tells Ho in Retrograde, it’s an “archive update.” For Lam, making the trilogy was “an experiment in walking that fine line between desiring opacity, maintaining composure, and sharing the messy subtexts.”

The Unshakeable Destiny

Sydney Film Festival

Premieres 13 June and 15 June, 6 pm, Palace Central Cinemas, Sydney