Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

|

Olaf Breuning, Life III, 2015, inkjet print on composition board, 264.2 x 381.0 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Suzanne Dawbarn Bequest, 2015. |

|

Neri Oxman (designer), Mediated Matter Group (design collaborator), Stratasys (manufacturer), Mask 3 Series 2, 2016, from The New Ancient collection, 2016, coloured synthetic polymer resin, metal, magnets, 34.1 x 40.5 x 22.1 cm. Collection of the artist and Stratasys, Rehovat. Image courtesy of Mediated Matter Group. |

|

Faig Ahmed, Hal, 2016, wool, ed. 3/3 (275.0 x 170.0 cm), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Suzanne Dawbarn Bequest, 2017. |

|

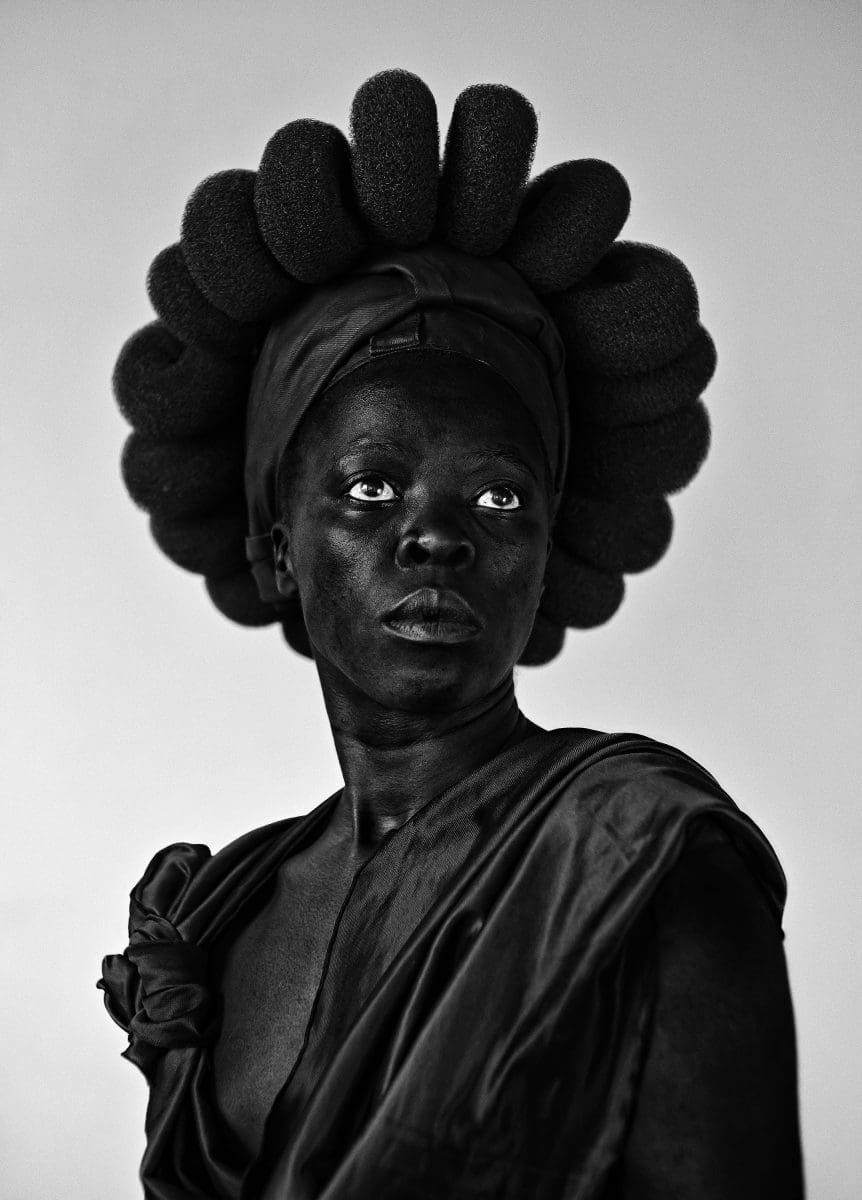

Zanele Muholi, Ntozakhe II, Parktown, 2016. Courtesy the artist and STEVENSON gallery, Johannesburg. |

|

Alexandra Kehayoglou with her work No Longer Creek, 2016, at the artist announcement for the 2017 NGV Triennial. Photo: Wayne Taylor |

|

50 Manga chairs (detail), 2015. Courtesy Nendo and Friedman Benda, New York. Photo: Kenichi Sonehara. |

|

Kushana Bush, The ones behind this, 2015, gouache and pencil, (66.5 x 44.0 x cm) (image), 95.5 x 72.0 cm (framed). National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with funds donated by Jo Horgan and Peter Wetenhall, 2015 (2015.402). |

Installation view of Xu Zhen, Eternity-Buddha in Nirvana, the Dying Gaul, Farnese Hercules, Night, Day, Sartyr and Bacchante, Funerary Genius, Achilles, Persian Soldier Fighting, Dancing Faun, Crouching Aphrodite, Narcissus Lying, Othryades the Spartan Dying, the Fall of Icarus, A River, Milo of Croton 2016–17 on display at NGV Triennial at NGV International, 2017. Photo: John Gollings.

It’s sprawling, it’s free and it will likely cement NGV’s place in the top 20 most attended museums in the world. What can we expect?

Opening this December, the National Gallery of Victoria’s first triennial is equal parts zeitgeist and revelation. Unlike other biennials and triennials, it didn’t start life with a set theme, just the ambition to present the world’s best art and design. The large curatorial team – whose expertise spanned contemporary art, fashion, design, and architecture – took a more intuitive approach and the result is a fascinating measure of our times.

The team shared an interest in new technologies, new ways of working and underrepresented regions. They identified artists and designers they believed were doing noteworthy work and, through discussion, whittled these lists down to 78 artists from 32 countries.

Many of the artists are responding to the major challenges of our day, such as the movement of people around the world, and the political and environmental catastrophes that can start those journeys.

Maidment points to the work of Alexandra Kehayoglou. She has recreated a river in her homeland of Argentina that is set to be flooded for a dam, and has turned it into a carpet of textured greens and blues. Maidment says Kehayoglou is optimistic. In the past, her work has helped stop other development threats. But it’s hard not see the carpet as just a layer over the top while everything crumbles beneath.

Then there are embroideries by the Australian Louisa Bufardeci, showing parts of the ocean where refugees have lost their lives, and a pile of loose paving stones by the Cameroonian artist Pascale Marthine Tayou. They are the sorts of stones that are prised up from the road and hurled during street protests. Here, Tayou has given them another meaning by painting them different colours, as a way of representing the many tribes that make up modern life. Coloured stones (Pavés colorés), 2015, is one of numerous works that have been acquired from the triennial for the NGV’s collection.

Other artists approach complex issues by focusing on the personal. Candice Breitz, from South Africa, tests our empathy skills with her multi-channel video Love Story, 2016. In one part, six people tell their own stories of why and how they fled their homes. In the other, famed actors Julianne Moore and Alec Baldwin repeat their words. The Irish artist Richard Mosse goes further, showing us what the flights of refugees actually look like, in his video Incoming, 2015-16. It was filmed over the Persian Gulf, the Greek islands, Macedonia, Turkey and Northern Iraq with a military grade, thermal imaging camera. The technology can pick up people 50 km away at night, and the black and white images have a semi-transparent, wraith-like quality. More than just a documentary effort, Mosse’s Incoming is also an essay on what we choose to see. It’s one of 20 major works, along with Breitz’s Love Story and Kehayoglou’s Santa Cruz River, 2016-17, that were commissioned for the triennial.

Some, like Zanele Muholi from South Africa, use more traditional means to address personal experience. Her commanding self-portraits are shot in black and white, with austere composition that draws attention to details of expression and costuming. In Ntozakhe II, Parktown, 2016, Muholi makes herself a dark halo out of the ordinary steel wool used for cleaning – an object heavily loaded in terms of the history and present circumstances of young black women.

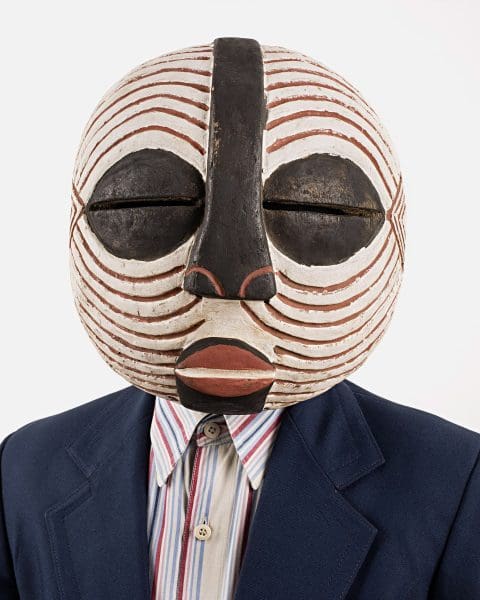

Muholi, alongside Tayou, is one of several fascinating artists from across Africa. Edson Chagas, from Angola, is another. His photographs read like strange passport photos. The men wear dapper suits with their faces obscured by tribal masks. They are reduced to symbols but retain an odd personality and energy, as though the men are about to walk out of the photo booth and back onto the street as proud demi-gods of a sort.

While others might consider Australian Indigenous art as another underrepresented region, Maidment does not, or at least, not at the NGV. There are four Aboriginal projects in the triennial – including a collaboration between Bula’Bula Arts and the international design practice Studio Alvaro Catalan de Ocón – which Maidment says is high for an exhibition of global scope.

As you’d expect in a triennial of this scale, there are plenty of big crowd-pleasers. There’s an installation by the Japanese superstar Yayoi Kusama that invites visitors to plaster the surfaces of the space with flower stickers, as well as fashion by the Chinese designer Guo Pei, and a massive video work by the Japanese art collective TeamLab, with swirling blue vortexes that respond to human presence. It will be all over Instagram in a flash. But the triennial is also an exhibition that plans to linger. It’s interesting to see that, in place of a traditional exhibition catalogue, the triennial has commissioned a sprawling research project with texts from different writers, as well as podcasts and films. There is no single reading here, but there’s certainly a lot to debate.

NGV Triennial

National Gallery of Victoria – NGV International

15 December – 15 April 2018