Family Ties

Using the powerful connection between mother and daughter, Generational at Madeline Gordon Gallery in Launceston, explores this intimate relationship with creativity and complexity.

Nathan Beard has long been wise to rituals, both strange and familiar, that create a sense of home. As a boy growing up in 90s Perth, his mother, who immigrated from Thailand, nurtured tropical plants in their suburban garden. He remembers shrines in the house, and time spent with women in the ThaI community. His upbringing, he says, felt ordinary.

“My mum’s garden was different—in the back of our house there would be banana palms, a portrait, herbs,” Beard says. “She had a really green thumb, but it was all about growing stuff we could use in the kitchen and that was before there were pots of coriander at Coles. What I had felt commonplace. But if I went to white schoolfriends’ houses, I [noticed] things like people not taking their shoes off when they went inside.” He takes a sip from his mug and gives a rueful laugh. “There was culture shock.”

Culture isn’t fixed. Identity, contrary to popular opinion, can be slippery. Beard has spent over a decade thinking about his inheritances, both material and immaterial. When I speak to him, he’s in London, readying works for A Puzzlement—a solo show at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts. He’s unguarded and expressive. He talks with his whole body. In a field that’s often self-serious, it’s easy to see why his photographs, sculptures and installations are infused with levity and play.

Take Low Yield Fruit. Presented in March at Perth’s sweet pea gallery, the show featured jackfruits, mangosteen and durian—Thai exports often dismissed by the West as spiky or smelly or not worth the effort. They balanced atop bronze Buddha heads, tenderly cast in silicon: mundane but monumental.

In White Gilt 3.0, a finalist work in the 2020 Churchie Emerging Art Prize, a series of photographs depict a slender pair of hands that stretch and flex and bend. They evoke Beard’s relationship to wai, a customary Thai greeting. “I wanted to create a moodboard aesthetic,” he smiles. “The wai is just a hands-clasped gesture—but I remember as a kid, feeling slightly uncomfortable performing it. I wanted to explore how in Thai culture, hands confer so much meaning and nuance. And how that intersects with my confrontation with it in a Western context.”

Beard, who studied at Curtin University, came to art via this Western context. We trade recollections of queuing up for Monet and Japan, an Art Gallery of Western Australia blockbuster exhibition, something of a cultural moment for Perth at the turn of the millennium. In 2013, his mother longed to reconnect with family. Her ancestral home in Nakhon Nayok, he says, had always loomed large in his imagination. When they returned together, it had been unoccupied for two decades. “There were photographs of my mum when she was 19, [relatives] who didn’t make it into our albums in Australia,” explains Beard. “It was frozen in time—everything was falling apart.”

Obitus, 2014, was shaped by the texture of these photographs, the gaps they represented. In one image, his mother stands in a living room half-obscured by a plume of smoke. In another, a black-and-white depiction of sisters sees the sprouting of green moss.

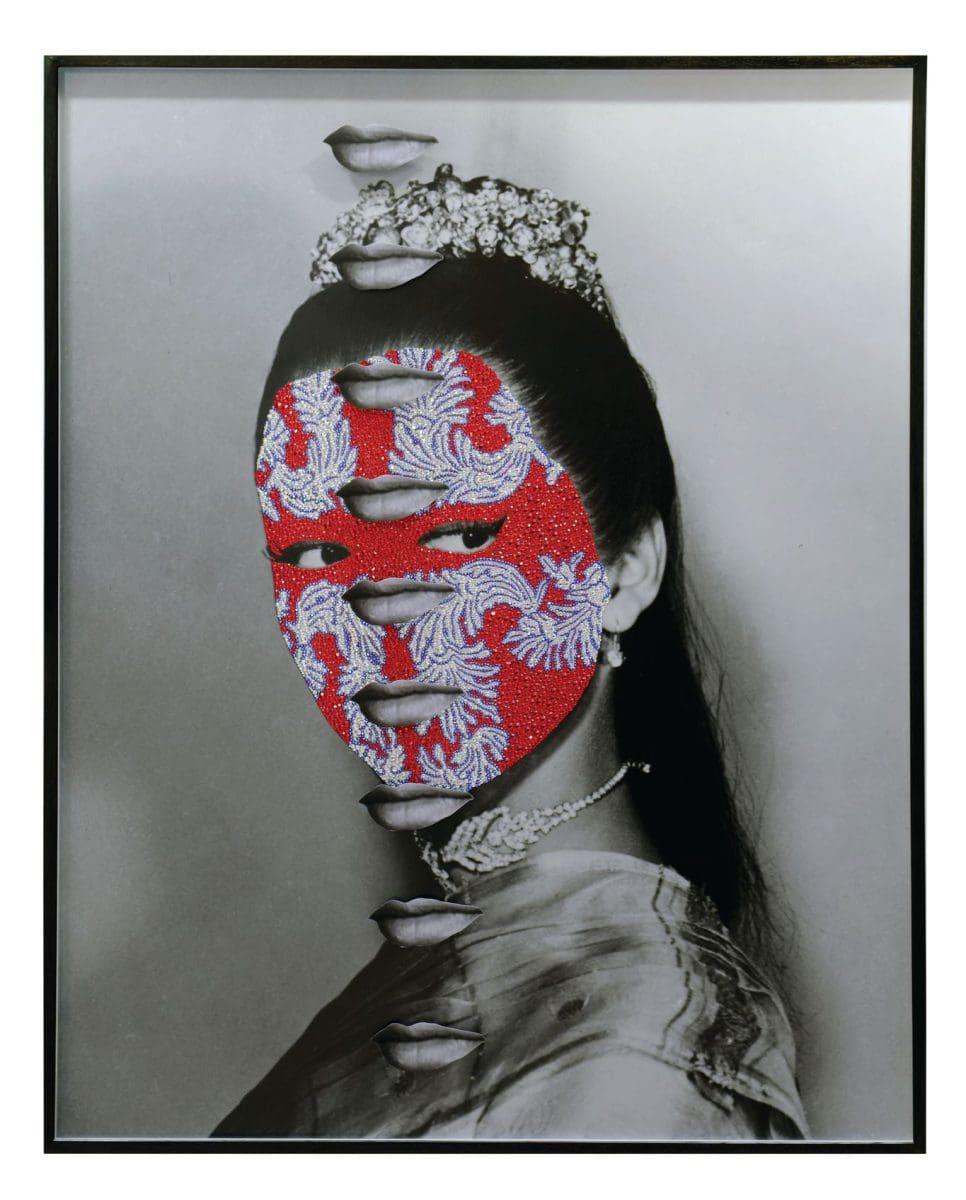

Memories can decay. Sometimes we embellish them. In Siamese Smize, which showed in 2018, Beard decorated images of his mother and her friends with Swarovski crystals, patterns evoking Thai silks and tourist kitsch. “It could be seen as a hodgepodge but there’s something really precious about just being encouraged to decorate an ornament,” he says. “It’s indebted to my mum’s taste.”

In 2019, his mother passed. To cope, he made Tender Ruin—profound images that document the story of her funeral. Through A Puzzlement, he’s still grappling with what he describes as a rupture in his own chronology. He’s become interested in objects over images. In the archives of Kew Gardens, he was compelled by the orchid, a flower associated with Thailand, a symbol of colonial interest in the country.

“You see how botanical interest in Southeast Asia overlaps with colonial expansion in the region,” he says. “[Thai] culture is always taking on different influences [although] Thailand was one of the only Southeast Asian nations that wasn’t colonised by the West.”

The show draws on references from the British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum and British Film Institute, including Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I. For Beard, the 1956 ‘chopsticks musical’, an orientalist portrayal of Siam and the West, was once a source of cultural pride. “It was like, ‘Hey, that’s an artefact depicting where my mum’s from,’” he laughs. For A Puzzlement, he will stack sculptural works based on artefacts in the British Museum on top of recreations of the shrine statues his mother brought to Australia.

“It’s this transference of the way that personal history, pop culture and institutional space all tumble together in different timelines and significances,” he smiles. “Assemblage will be an aesthetic driving force.” He pauses. “The acknowledgement as far as I’m concerned is the fact that without my mum’s influence, this is what I have to rely on.”

A Puzzlement

Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (Perth WA)

28 October—8 January 2023

This article was originally published in the November/December print edition of Art Guide Australia.