Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Nalda Searles—inexhaustible artist and WA Living Treasure—is being honoured with a historic retrospective as part of the Indian Ocean Craft Triennial. Finders Keepers, at Mundaring Arts Centre, brings together a selection of her garments, baskets, jewellery and textile objects. Together, they tell of the septuagenarian artist’s strong relationship with the bush, which is both her muse and her treasure trove of materials. Sheridan Hart spoke to Searles at the gallery as she unpacked artworks, some 40 years old, some works-in-progress..

Sheridan Hart: Where does the title Finders Keepers come from?

Nalda Searles: My work is about finding and keeping. What we’ve got here is some kept stuff, some sold stuff and some new stuff. Three lines. The people who bought it very kindly agreed to loan it back: Kerry Stokes, Art Gallery of WA, Ararat Gallery TAMA, Edith Cowan University. There’s something to be said for getting your work into good collections. Then people can see it again!

SH: Shall we look at some of the new works?

NS: This one is under way. It’s a red coat with human hair on it. I’ve always collected different people’s hair. I put it on with a felting needle. The coat belonged to the painter Lorraine Biggs. It’s quite grizzly. Now, look in that bag over there. This old rope was my clothesline for about 30 years. I took a red woollen blanket that was given to me by a friend in Melbourne and I chopped it and I stitched it around the rope. It’s called Suture. It’s intestinal! Twelve metres stitched and a few metres unstitched.

SH: Many of your older works are brown, natural tones. This red really pops out! What attracts you to it?

NS: I had a big shock in my life: I couldn’t go bush anymore, so I’ve had to change. I had to go more into myself. That’s how these artworks have happened. It’s a reaction to life.

SH: Lately, you’ve had to draw more on the materials you collected in past years.

NS: I’m a hoarder of sorts. I find something and I sit with it for a while before I decide if it’s the right thing. Look at this. I made the ceramic out at Blackstone in the desert. I took it home and added this precious little twig that I had kept for a long time. It had grown around a rock. It’s a root from a cajeput tree, a desert paperbark from the Pilbara. It’s like a bird drinking at a waterhole.

SH: You’ve done a lot of teaching and workshops. Has there been an upswing recently in the sharing of craft skills?

NS: It’s very important to me that people enjoy the camaraderie of being together with like-minded souls. Good friendships have grown out of my workshops.

I’ve done, I can’t tell you, at least a thousand. I started in 1982. Initially I was showing people how to make a ‘basket basket,’ but now I teach much more free. It makes my blood boil when I see people doing perfect baskets.

You can’t show somebody in eight hours how to make a basket. All I can do is get people started. I want them to get a feel for how I learned. It’s up to them to commit.

SH: Basketry has persisted all throughout your practice and underpinned your sculptures and jewellery.

NS: It has been a great prop for me. My baskets are unique in the world, the method I used. I used bones, wood, feathers. I’d hardly get one finished and I’d be onto the next. It went on like that for years.

When I went to Curtin University to do painting, that changed me a little bit. Then I got involved with Aboriginal people and that changed me some more. Then Mary [Ngaatjajarra artist Pantjiti Mary McLean] went into care in Kalgoorlie. That changed me again. I feel very sorry and sad about that, but she keeps pretty well, all up.

SH: There’s a good sense of fun in your work. How serious or playful is the making process for you?

NS: I take it very seriously, but I still have a good, dark sense of humour. I never just push something out for fun. This basket, those necklaces, they’re not frivolous. I make everything with real commitment. You have to when you want to keep moving. That’s really important. You could lay all my stuff out in a line and see the development.

Humour is important too. There’s always something funny happening if you look. This red, hairy coat is humorous, and also a bit spooky. Humour and commitment.

SH: Let’s talk about your jewellery. Jewellery is often discussed in monetary terms, but your materials have other valuable properties.

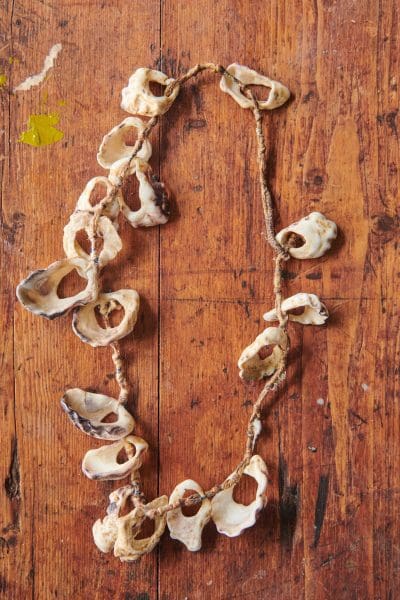

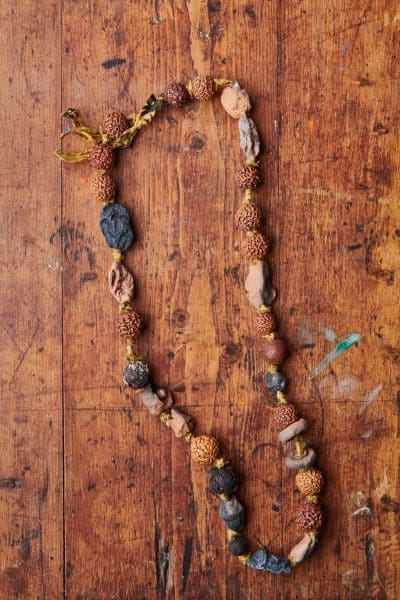

NS: From the very beginning I saw the potential of feathers, quandongs, sandalwood seeds, gumnuts, stones with natural holes in them. Not in a kitschy way, but in an important way. That little necklace there, it’s quite beautiful. You could say it’s just shells on strings, but it’s more than that.

These are called dentalium. Throughout history people have made this type of thing. To me this is more precious than rubies or gold. When you decide to make a necklace from something, you can’t just stick it together. You have to make it very carefully so you know it’s going to last.

SH: Are there artworks here that you think of as milestones?

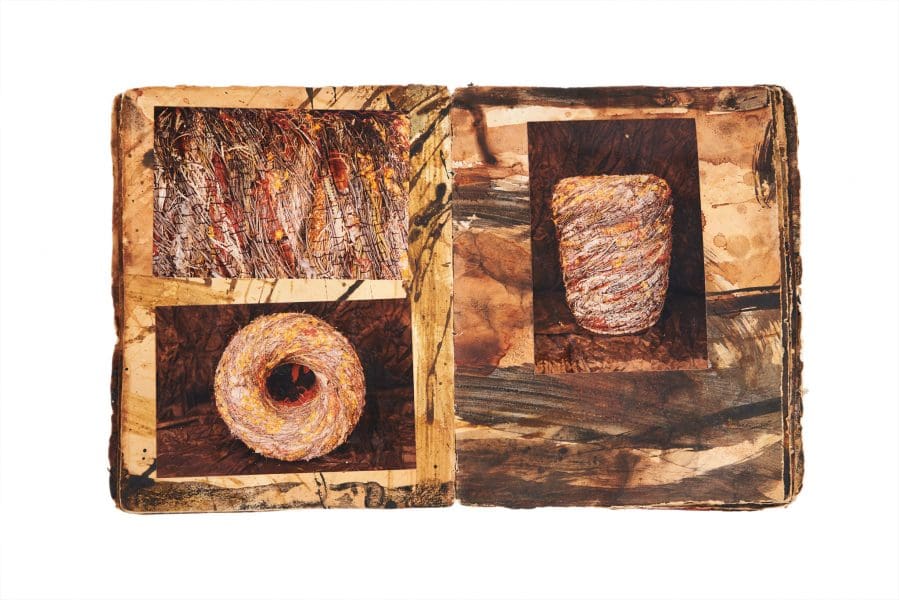

NS: Look in that box. It’s a big book, take it out. When I finished studying, I wasn’t sure if I was an artist or a craftsperson, thanks to Dr Robert Bell. He used to throw that argument up all the time.

So, I took a room at PICA. I got four metres of paper, boiled up tubs of plant dye and basketry materials. For two weeks I sat in that room and I drew on the paper. At the same time, I made a big basket, a good one. I was trying to feel if there was any difference between the two. Friends came, [WA artists] Cecile Williams, Claire Bailey, Linda van der Merwe, Mary. After two weeks I tore the paper up and made this book.

SH: And did you answer your question?

NS: I can’t tell you. Creativity is creativity. There’s no answer, is there?

SH: After many years of practice, do you have any advice for young artists starting out?

NS: It’s good to hold onto a few pieces, so that if something comes of it, you’ve got a nice little bank of ideas. Look, I can’t speak highly enough of the importance of art, for anybody, for everybody. So, I would say, do anything! It doesn’t have to be set in concrete. It can be meandering. That’s a direction. It’ll be good.

Finders Keepers

Nalda Searles

Mundaring Arts Centre

14 August – 31 October