Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

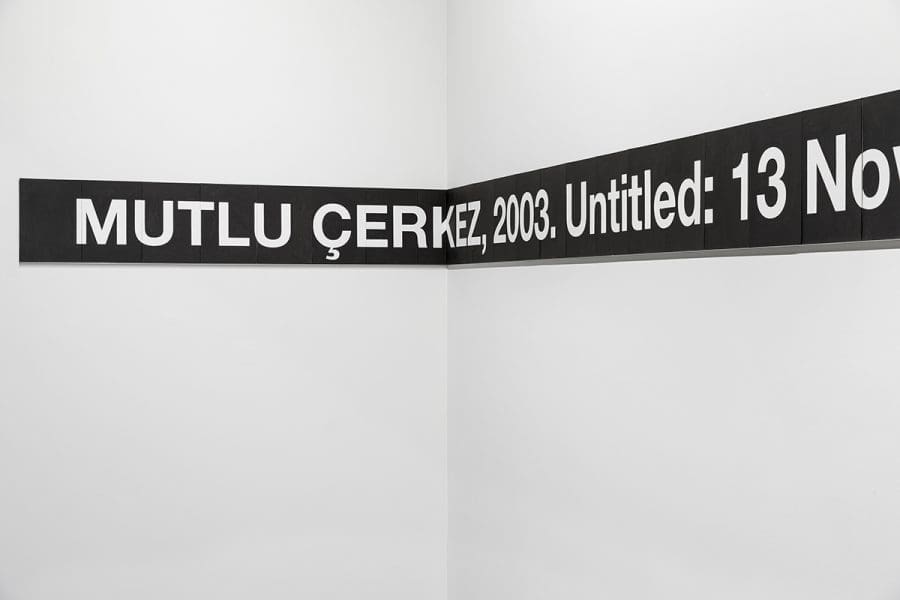

The dates in the title of the retrospective exhibition Mutlu Çerkez: 1988–2065 are a little confusing. But in a transcript of a lecture given by the late artist, published in the exhibition catalogue, we learn why his artwork titles include a future date. He theorised the model typical of many artist’s careers in which future works render past works redundant. For example, Mondrian is known for his abstract paintings with black lines and blocks of primary colours, not his earlier landscapes even though they also contain his trademark horizontal and vertical lines. To circumnavigate this problem Çerkez proposed a future date when the piece would be remade (which in fact only happened twice.) Each work would have an original and a copy.

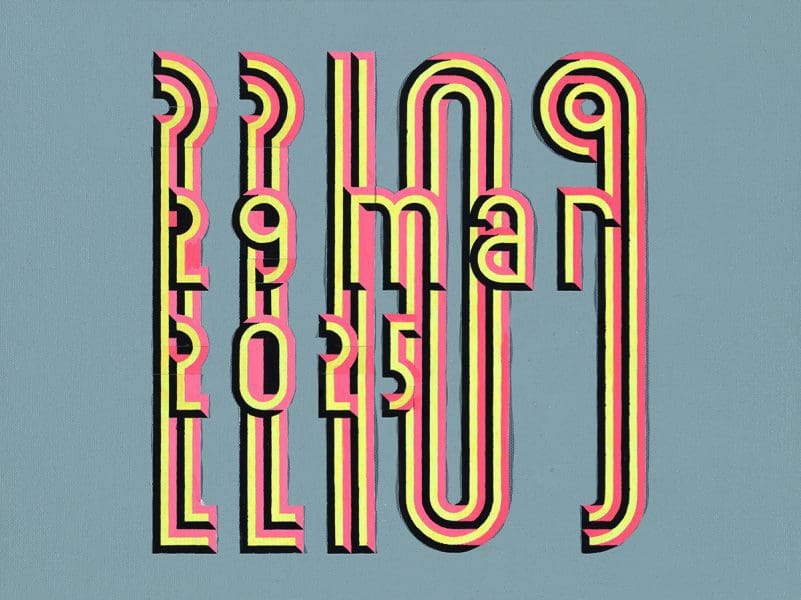

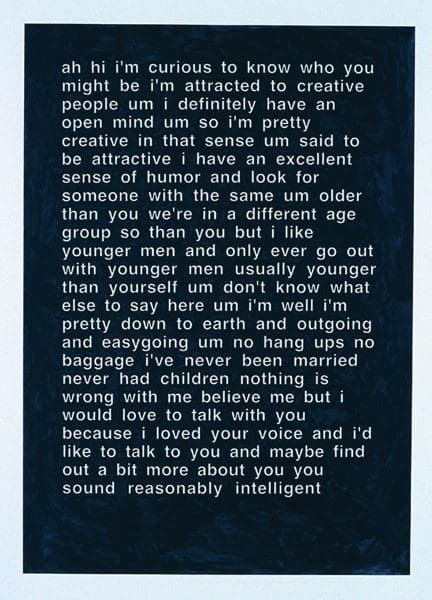

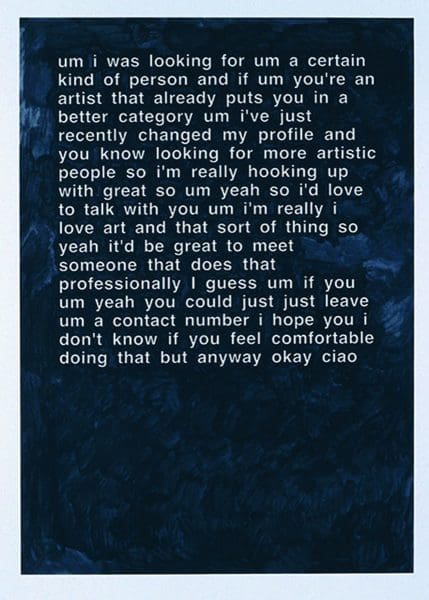

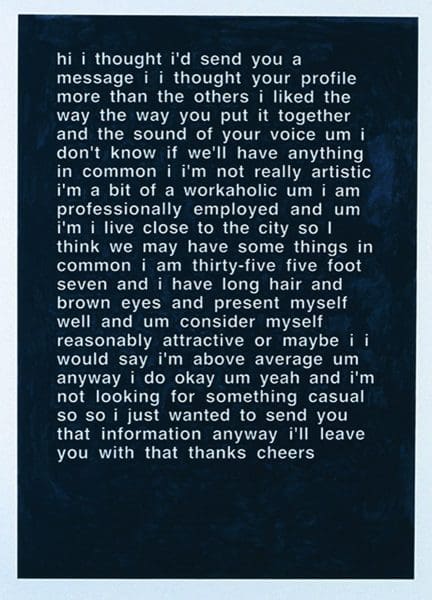

Active in between 1988 and 2005, Çerkez’s practice is heavily conceptual, containing doses of minimalism and the aesthetics of late modernism. His oeuvre includes photorealist paintings, transcripts of voice messages received through a dating agency, and numerous posters, all subject to curious logic.

As the co-curator of the exhibition and director of MUMA Charlotte Day says, “Çerkez set up very specific parameters around his practice yet they were not rigid. He often challenged his own rules and assumptions. As such the status of the work is always shifting; it remains to a certain degree elusive.”

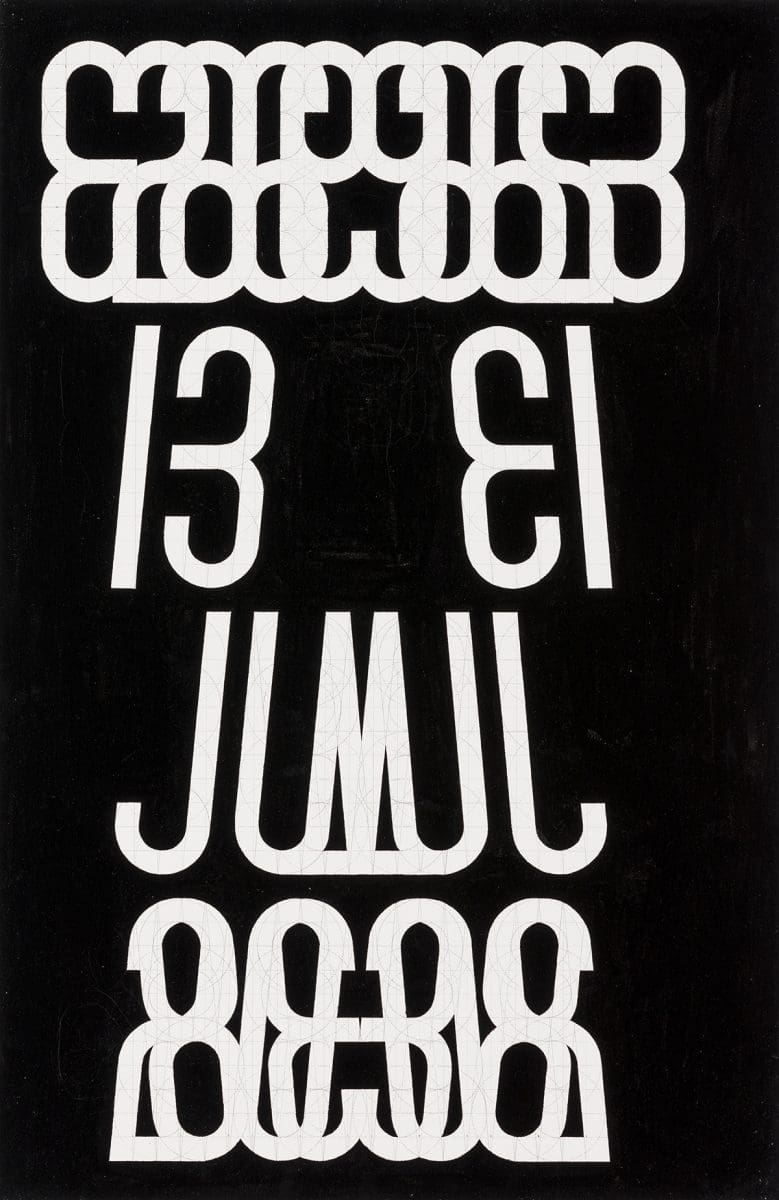

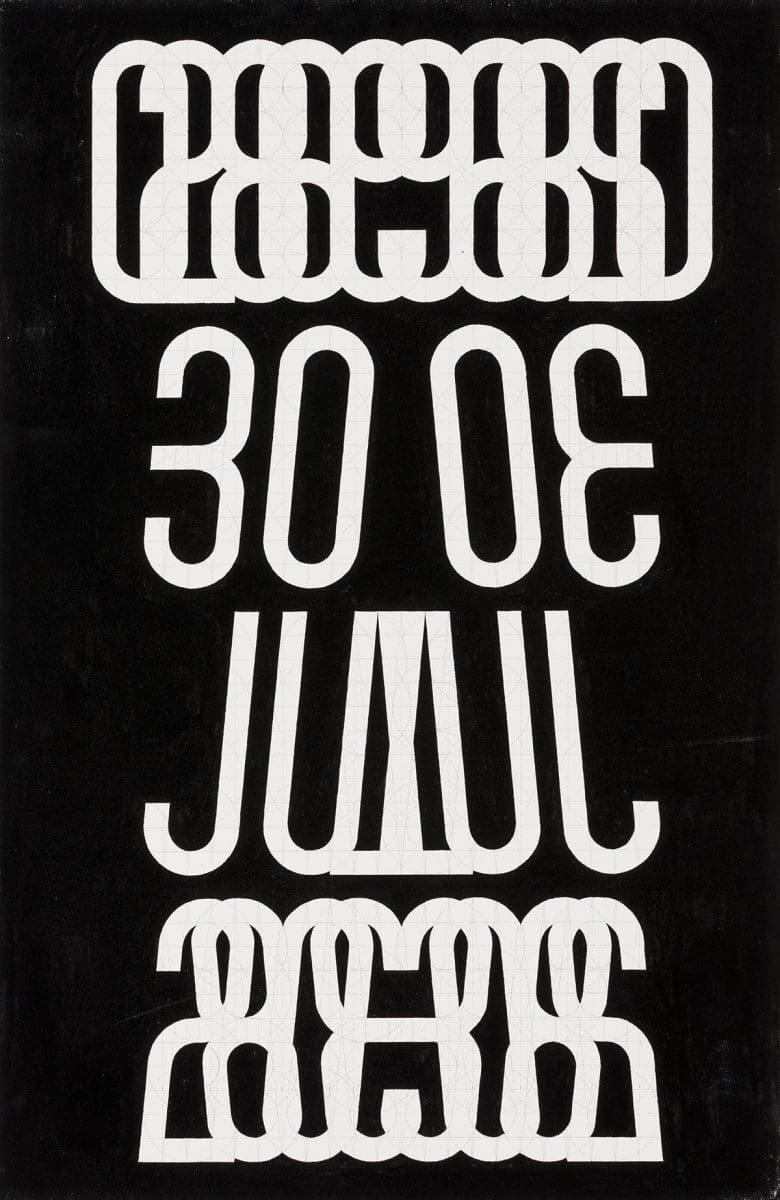

Çerkez’s interest in repetition extended to popular culture, in particular Led Zeppelin’s music. Between 1995 and 1999 he created cover designs based on bootleg LP sleeves. As bootleg recordings of Led Zeppelin’s live performances create a ‘doubling’ of their songs, with slight differences, so do the doubles that Çerkez made of the designs that enclosed them.

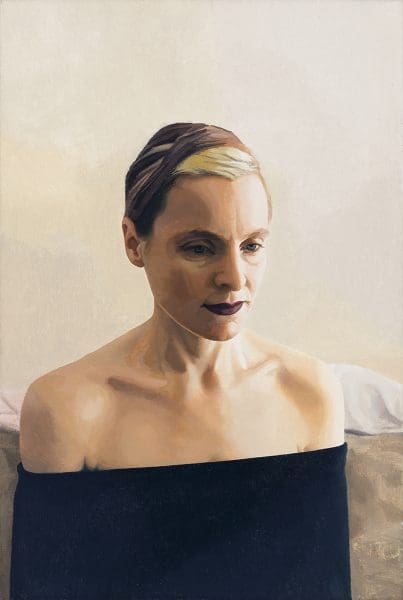

The exhibition includes a series of self-portraits, but rather than provide access to an ‘inner life’ of the subject, they remain coolly distant. “They direct you into thinking about him, the artist,” says Day. “But when you view them in the context of the suites of works they’re among, they don’t really tell you so much about the artist. They are more about the idea of the portrait of the artist.”

A preoccupation with translation in his practice is relevant to our current media-saturated moment. “Many of his artworks involve forms of reproduction from one media into another, and creating variations on a theme,” says Day. “These works were made in the early days of digital media. It’s interesting that he was already working in that space.”

“In our research we looked at the exhibition contexts in which his work was presented,” says Day. “In international group shows often his Australian-Turkish-Cypriot background was important to the narrative. It has been interesting to examine these historical contexts, as well as his artworks, from the perspective of today.”

Çerkez was active and influential in the Melbourne art community during his time, with close relationships with artists such as Callum Morton, Marco Fusinato and Rose Nolan. “An artist, even when they have such a strong presence and influence up to a certain point, when they’re no longer with us the attention can easily dissipate,” says Day. “Hopefully an exhibition like this introduces Çerkez’s work to a new generation of audiences and art lovers.”

Mutlu Çerkez: 1988–2065

Monash Museum of Modern Art (MUMA)

10 February – 14 April 2018