Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

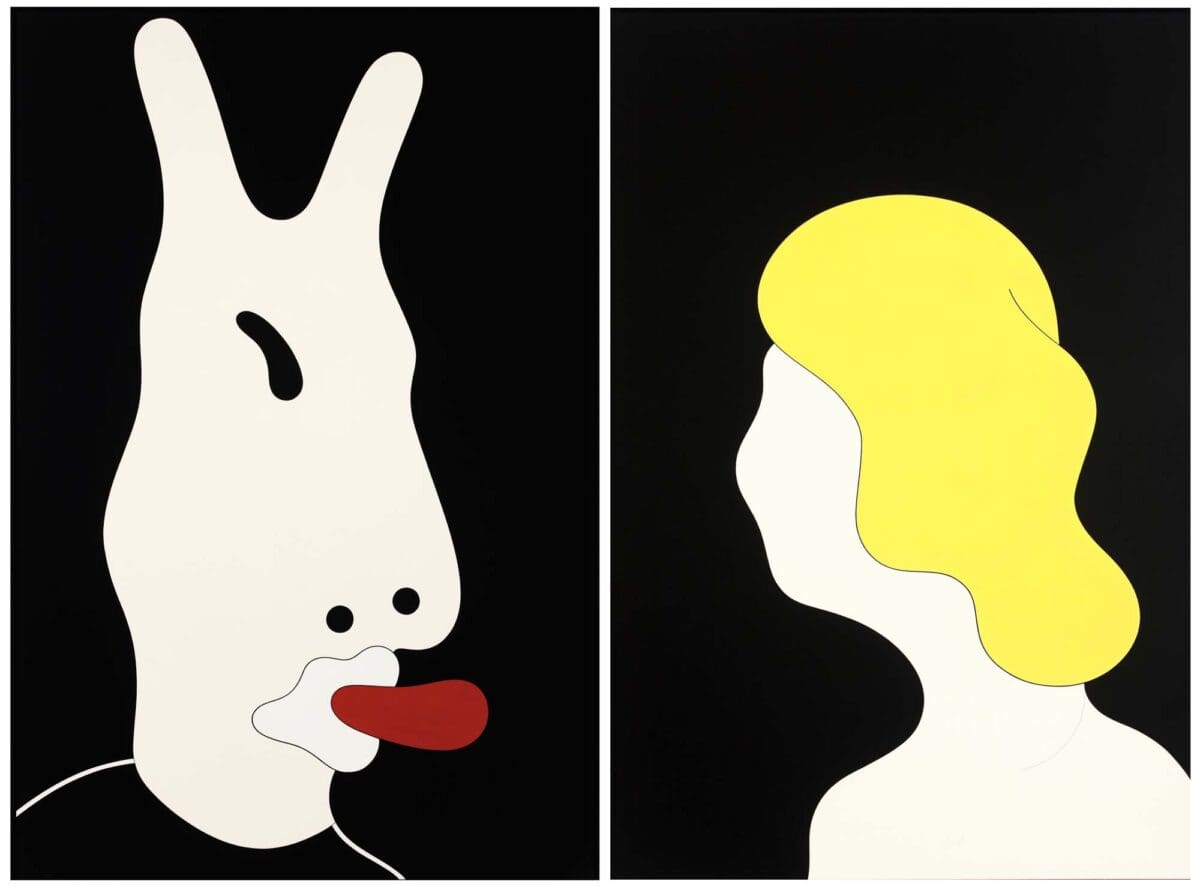

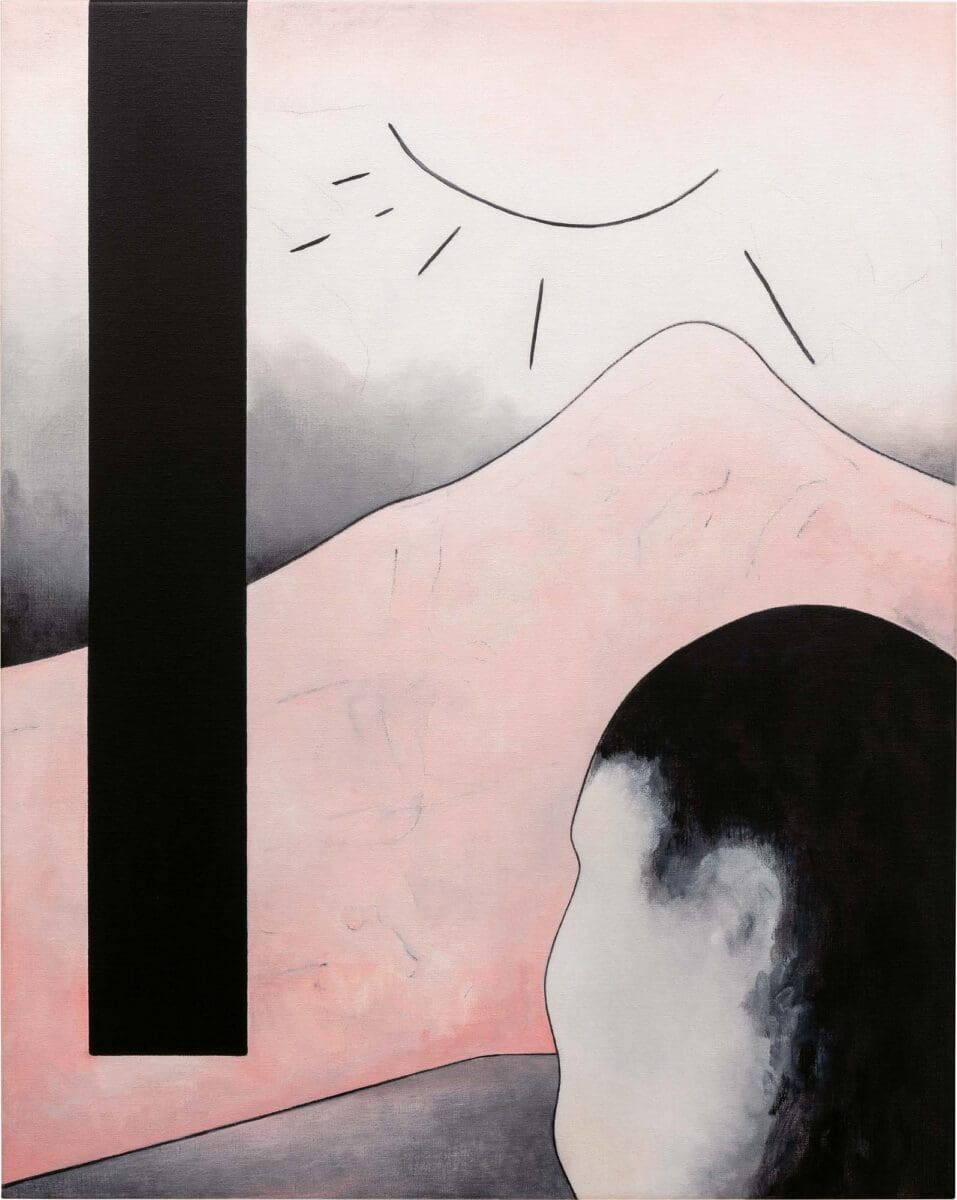

Meaning lies somewhere between humour, absurdity, and mortality in Brent Harris’s paintings and prints; his curved lines often hold human-like forms, each searching for moments of revelation, salvation or connection—just like we all are.

Born in Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand in 1956, Harris moved to Melbourne in the early 1980s to study art, shortly after coming out as a gay man. As the HIV/AIDS crisis began, Harris painted the series that cemented his early career, The Stations, 1989, featuring 14 geometric works referencing the Stations of the Cross, religious images depicting the journey Jesus undertook on the day of his crucifixion. Even now, religious and art historical imagery from Mary Magdalene to Colin McCahon to Philip Guston resonantly infuses Harris’s work.

Over the last 40 years Harris has innovated upon his flattened surfaces and developed his printmaking practice—all while carefully instilling quiet emotion through his art. With a recent survey in New Zealand, Harris is now exhibiting with an Australian showing of 40 years of work, titled Surrender & Catch. Currently at TarraWarra Museum of Art, the show will travel to the Art Gallery of South Australia in mid-2024. Ahead of the survey, editor Tiarney Miekus caught up with Harris in his Melbourne studio, talking about dreams, death, surfaces and curves.

Tiarney Miekus: You’ve often talked about the importance of the dream stage to your work

Brent Harris: Yes, of accessing the subconscious.

TM: Exactly. But are you a chronicler or teller of dreams—do you write them down, talk about them, interpret them?

BH: I do. But look, I’ve had three shrinks over time, mainly to deal with my family when I felt most anxious about the situation there. And the last one was just bloody excellent. I saw him for about five years. At the time I was making monotypes that had a definite dream-like quality. During the course of a year I made around 100 monotypes based on intuitive mark making, each having an otherworldly aspect. And I often showed my shrink the results, and we would attempt interpretation, based around the narratives of my inner psychology.

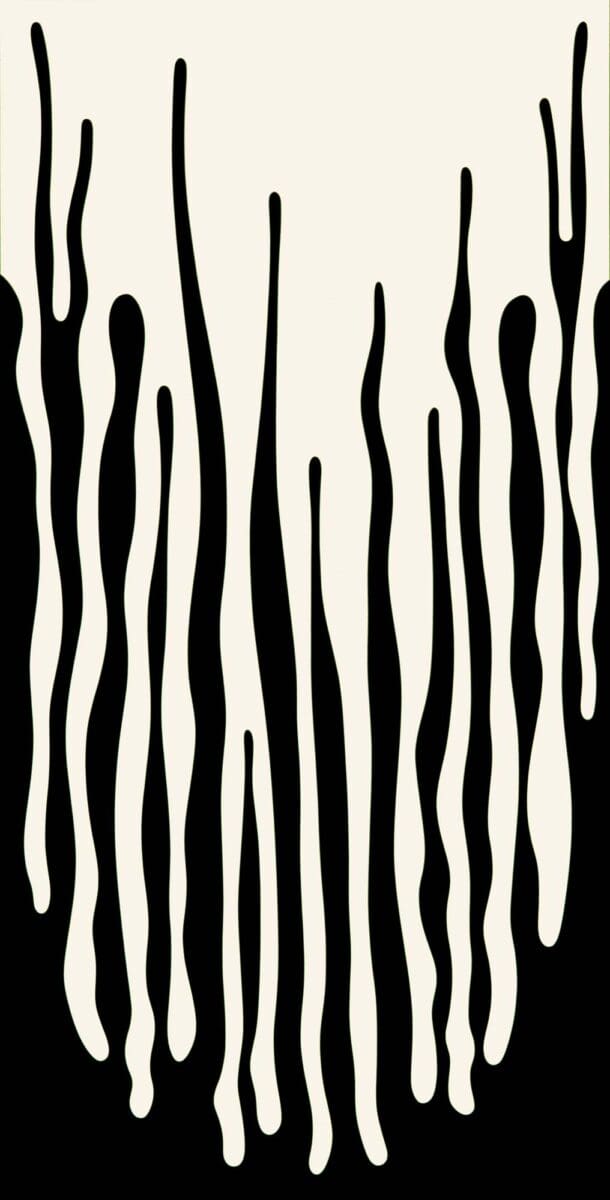

The prints were developed using the ‘dark field’ technique, where you start with black ink rolled on surface, which you then start wiping away until, possibly, imagery appears. As such, it resembles surrealist automatism. A lot of very unexpected imagery appeared over that time! For instance, I have this one where it looks like some forlorn character is carrying a dead baby. And then this one almost looks like…

TM: An ultrasound?

BH: Yes! A womb. And then there’s this man carrying what could be this dead baby. But when I started making that, I had no idea what was going to come to the surface. I’m not thinking, “Now I’m going to do this dead baby being carried around.”

It’s an amazing process, the monotype. But you have to follow it, and I have learnt that you can only really do it when you’re in the studio by yourself, in fact surrendering to it, and seeing what you might catch— rather than performing in a formal printmaking studio situation with the technician sitting around waiting to print the damn thing.

So anyway, I’d take them to my shrink and we’d talk through them, almost like dream analysis. For instance, another I’ve called The Prophet has this looming character with a crumbling halo, and he is hovering above a crowd. I said to my shrink, “I think it’s a failed prophet.” And he responded, “You don’t need to use the word failed, all prophets fail.” So, I just called it The Prophet. I don’t know where this stuff comes from, but we’d analyse it—and most of it seems to deal with mortality and death: one’s own and others. It’s probably the driving question in my work.

TM: What does that mean: “death is the driving question”? Like the unknowability of it? The anxiety?

BH: No, it’s not anxiety. It’s more like, what the hell is going on? [Laughs] You live this life and then you get snuffed out. What’s the point? Some friends of mine who’ve had such rich lives, one in particular in the art world—about five years before he died he was really irritated about impending death. He’d accumulated all this knowledge and then… just to die? But he’s left a huge legacy nevertheless.

TM: Do you have that irritation?

BH: No, not an irritation, but I am 67 now. My own mortality is starting to creep up on me. Thinking about that first series of Station works [the aforementioned 1989 series], the quite abstract ones, that admittedly was quite an engagement with mortality as a subject, at an early age. I was around 30 when AIDS arrived, and I was right in the thick of it and that whole Stations narrative of “judged this morning, dead this afternoon”— death was right there in front of us. It was very quick in the 80s, even in the 90s—death came very quickly. Some of these early Station works are going into the show at TarraWarra, alongside a more recent series of paintings dealing more figuratively with the same subject.

TM: Thinking about that earlier period of your life: you got married in New Zealand at the age of 19, then soon divorced, and you came out as gay. Then you moved to Melbourne and started studying art in the early 80s, and then the HIV crisis began—I wondered if it felt like strange timing?

BH: No, I see what you mean, but it didn’t feel like that. Robert Leonard [now director of Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art] picked up on something that I had said: that there were two castrating factors in my sexuality. One, of course, is to do with the father and all that Oedipal stuff. The other was AIDS. So, my sexuality was affected twice. At the beginning of the 80s I was happily engaged sexually, then this bloody shutter comes down. It’s interesting, when I talk about my father and our estrangement, people think, “Oh it’s because he’s gay, his father didn’t like that.” But it’s got nothing to do with it. He had no issue with me being gay. The whole issue was his sexuality and his abusive behaviour.

TM: I understand that once you left New Zealand in 1981, you didn’t return until recently for your exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

BH: Yes, there was a large survey show of my work in Auckland earlier in 2023, The Other Side, curated by Jane Devery. And yes, I’ve spoken about those very troubled feelings because it was quite central to the show in Auckland. I’m basically an Australian artist, but born and formed over there. I stayed away, until after my father’s death in 2016. I didn’t see or speak to him for the last 25 years of his life and I didn’t see my mother during those 25 years either. I actually started exhibiting my work in New Zealand in 2018 with Robert Heald Gallery in Wellington, and that has led to some sort of re-engagement with New Zealand relationships.

TM: For someone who is influenced by religious iconography and those stories on death and salvation, alongside meditation, would you call yourself religious in any sense?

BH: No, I’m not religious, but I am interested in all those stories and the questions they pose. All religions attempt to make sense of death, but more broadly these stories are above all about the human condition we are all stuck in. I did learn meditation when I was 17, transcendental meditation, and I’ve always had a yearning towards something other, something else. I still meditate, and often about nothingness and death. When you’ve taken everything away in your mind and you’re still present, sitting there breathing, it’s an interesting place.

TM: With the upcoming survey, the title Surrender & Catch comes from a phrase that your psychologist introduced to you. Can you talk through that?

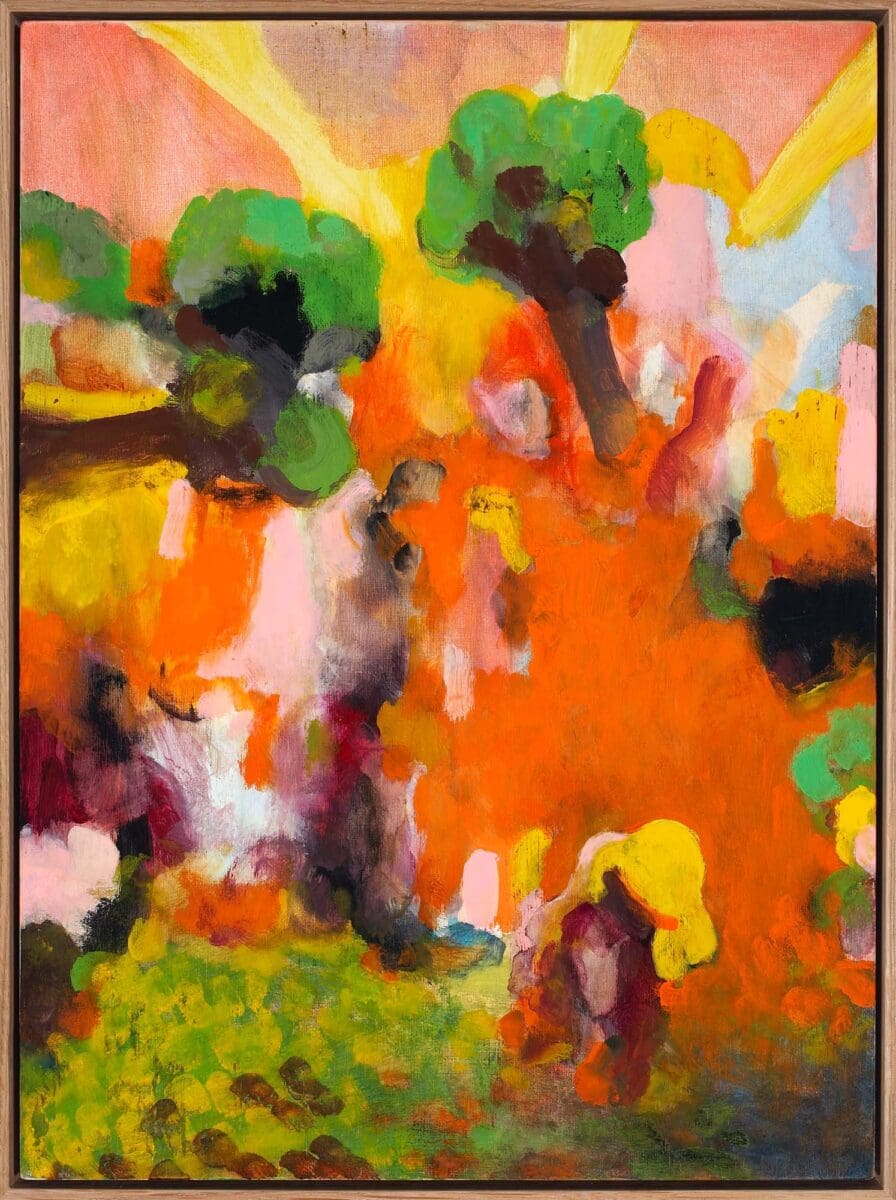

BH: Yes, he brought it up when I had returned from a residency in Rome, in particular in relation to the way I was approaching painting. In Rome I had started making small colourful paintings on panel, initially titled ‘the ecstatic moment’. These quickly developed into a larger series titled Surrender & Catch. The term comes from the German-American sociologist Kurt H. Wolff’s theory of knowledge as “surrender and catch”, suggesting you have to surrender at times in life to take advantage of opportunity or chance. Surrender for me tends toward suspending disbelief. I still find it interesting in the creative process as an artist, even if it’s just the anticipation of the next image; I’m continually open to revelation. That sounds religious to say revelation, but I want things to be revealed.

TM: Do you get a moment of revelation when you’re making art?

BH: Of course, but it often happens at other times too, including in the middle of the night. I keep journals and make these little drawings in the night; I’m not a great sleeper. Nighttime consciousness is great for loosening things up; often one thing connects to another in unexpected ways.

TM: Looking around your studio right now you can almost see these connections. But I’ve noticed some of the newer paintings have a graduation of shading alongside your signature flat colour— when did that come in?

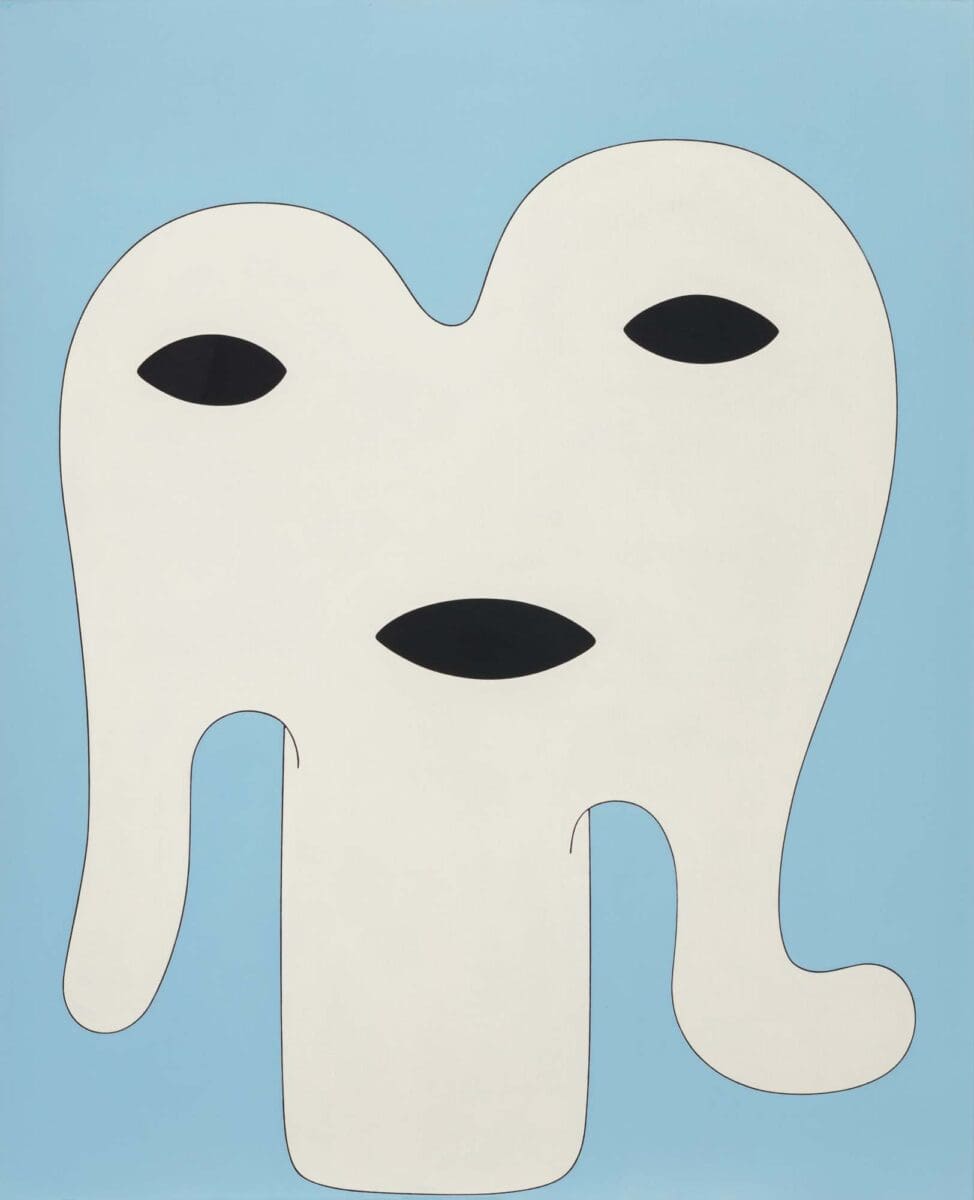

BH: My painting used to be very flat, but my engagement with emotion, of trying to get emotion onto a surface that’s so flat, is generally through the curve, which I connect to the body. The curves are in most of my paintings, they have a sensuality to them. The gradations operate similarly.

TM: Was there a moment when you first painted the curve and realised its significance?

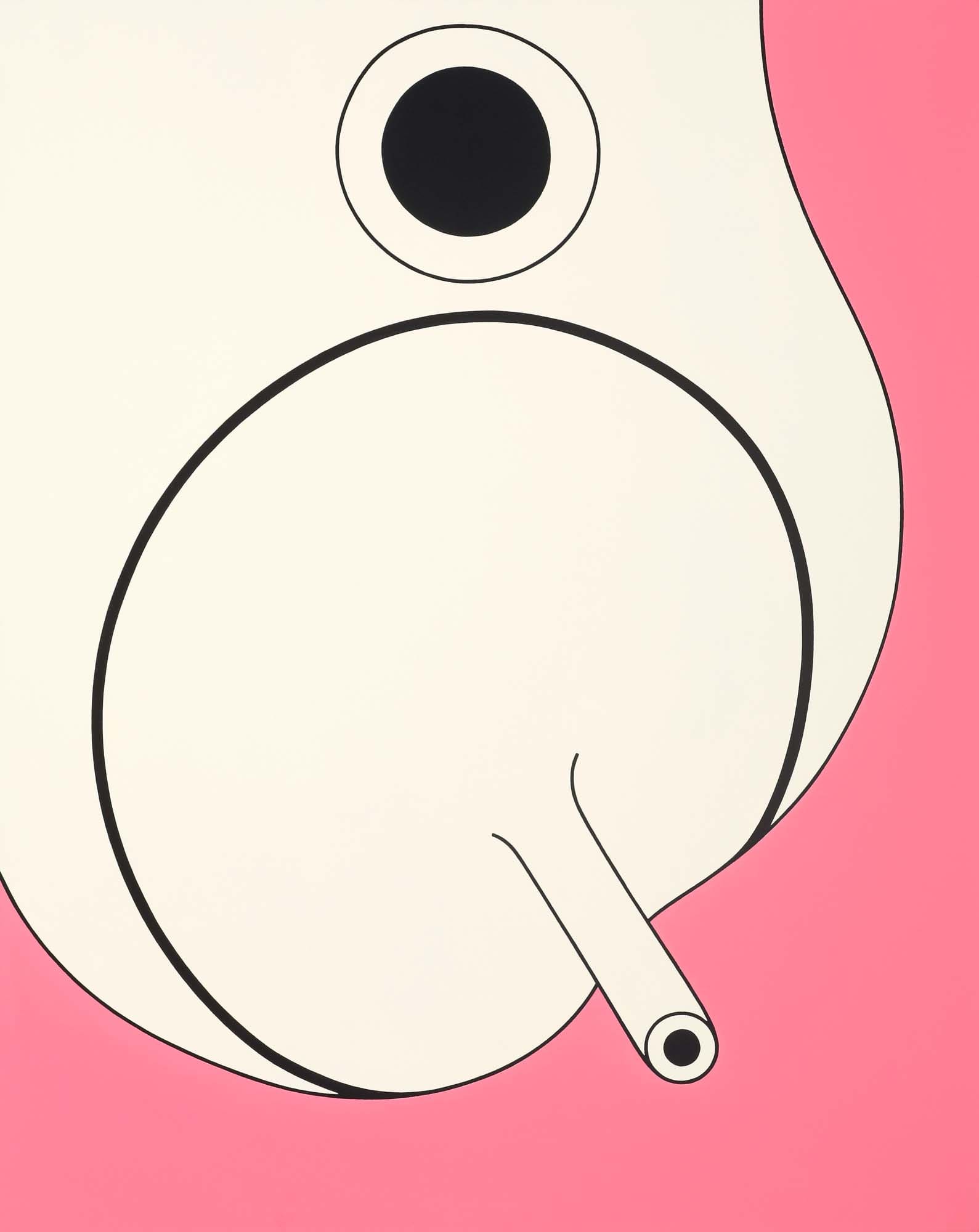

BH: Initially in the early 90s with a series of black-and-white paintings titled Body. Then moving forward into a series of pink paintings [Just a feeling, 1996]. There are six in total, and they were libidinally driven, if you like. There’re breasts, scrotums, orifices—but how do you express that on a flat surface? For me it was getting that curve. They’re quite playful.

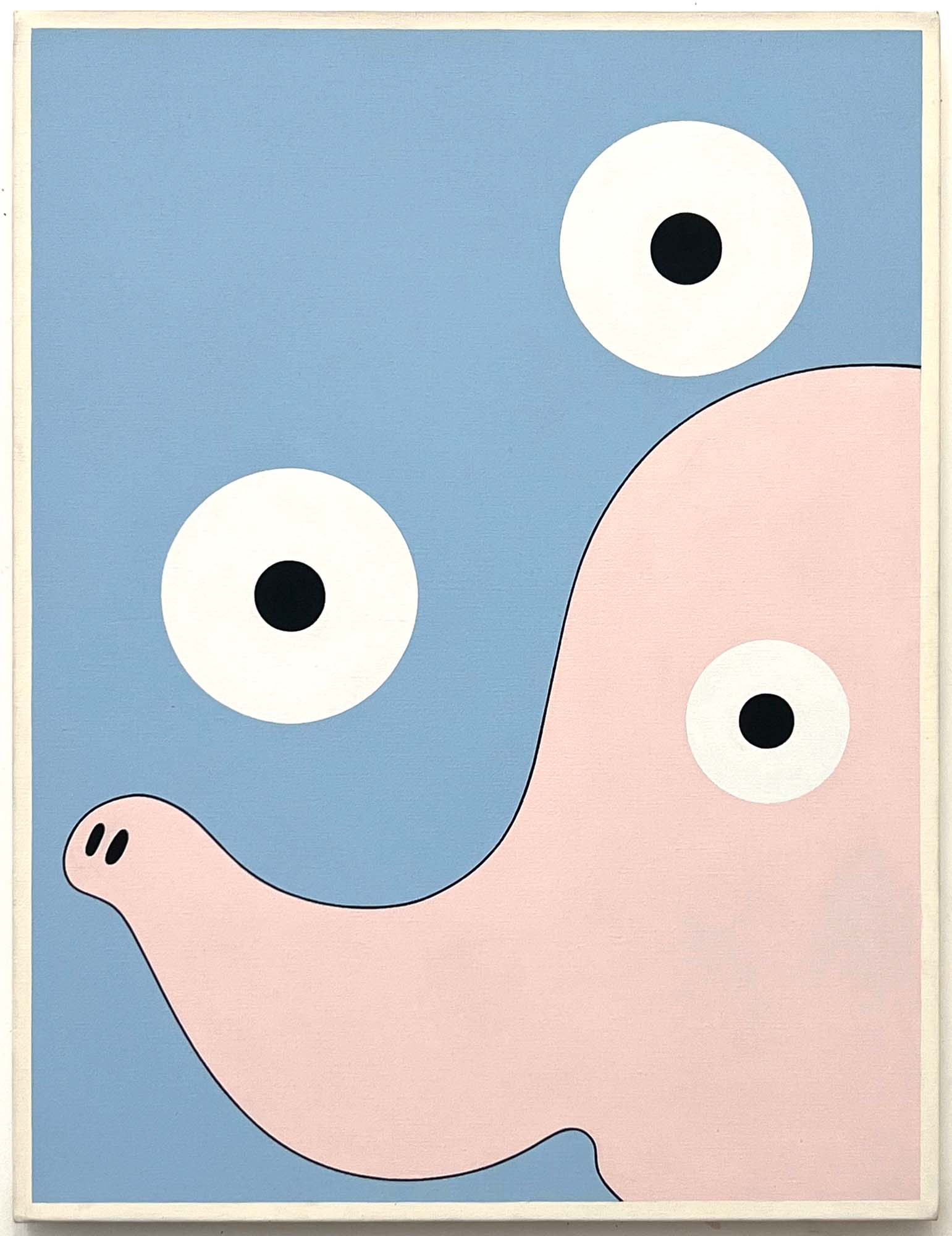

I couldn’t hold onto the purely geometric as present in the 1989 Stations, and a sense of absurdity came into my work through Mike Kelley’s influence. There’s a big black-and-white elephant painting that’s in the show at TarraWarra called Appalling Moment [1994]. While working on quite abstract drawings a stupid elephant trunk appeared; I allowed this to remain and started to develop more playful imagery around it. I identified this acceptance of something quite absurd as my ‘Appalling Moment’.

Of course, the other weird shape in my work, even way back, is this eye. It’s all-seeing, it can also work as an orifice, as vision, a portal into another realm. Sometimes it appears in the corner of a painting like an escape route, this possibility on the flat surface to go somewhere else.

TM: You clearly reflect on your works so thoughtfully, but with this 40-year survey, do you find you’ve gained a higher faculty to reflect on them as time has gone by?

BH: It’s interesting, this being able to reflect on the past when you get older; obviously reflection becomes more complex when time has had its way. Of course, now, I have a different attitude when I look back, and I want to pull the past up to speed with my current thinking.

Walking into that show in Auckland was pretty weird, seeing 30 years of my life laid out in images behind me. When you’re making them, you’re not thinking 30 years in advance—I didn’t know what they would add up to. I didn’t have any relationships in mind when I was making them, I was just trying to find my way. But now, you do become more reflective; everything’s more informed by life lived, the histories of art and my own histories.

TM: Do you have to be careful that you don’t become too informed? Like too habitual with your thinking or creating?

BH: I don’t feel like that, but I know what you mean; obviously an aging artist can be prone to repetition. I don’t feel I’ve got a fixed narrative, other than this management of my own engagement with the human condition. I do have a head full of imagery though, built on over the years, imagery of my own and others, that I’ll draw on as I like. Time will have to be the judge.

I’m not driving any political agenda that keeps me in line—you know, the personal gets political quickly enough without any over determination. For instance, I’ve had people [curators, writers, audiences] queering me… but I’m not very queer. And I’ve never really identified as a gay artist. Robert [Leonard] in his recent writing, asks, how do you feel about being brought into that? And I said, “Well, I just don’t feel that I’m queer enough, you know? I’m just a standard old homo.” [Laughs] And Robert quoted that! But, at the same time, I don’t mind being called a gay artist—I’ve never not been gay. It’s never, ever been something I’ve shrunk away from. Maybe it informs my work.

This article was originally published in the January/February 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.

Brent Harris: Surrender and Catch, on tour from TarraWarra Museum of Art, is now showing at the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Brent Harris: Surrender and Catch

Art Gallery of South Australia

6 July—20 October 2024