Whenever I think of artists working with architecture as a subject, or even artists doing some kind of collaboration with architects, I imagine it’s a very high-toned affair: you know, classy. Like a rock band doing a show with full orchestral backing, it’s one of those cultural collisions that make so much sense you wonder why it has hasn’t happened before.

When I was a teenager I liked to repeatedly check out a book from my high school library that was, inexplicably, a catalogue of illustrations for draughtsmen to consult when coming up with ‘artists depictions’ of yet-to-be-built building projects. The book had whole sections on drawing people to scale, producing shrubs and trees for the forecourts of buildings that looked like they might one day be built on Tracy Island, and angular bus stops and metro stations for modest European cities of the future. The book was an illustrator’s guide to a visual utopia and it touched the Asperger’s part of my brain that likes social order and forced perspective, the kind of things you find in train sets or overly ambitious Lego projects.

It never occurred to me that art and artists, and architecture and architects, were anything more than second cousins, awkwardly acknowledging each other at family funerals, but never really getting together, let alone collaborating in any meaningful way.

Architecture is about order and standing in the landscape for decades, maybe even centuries, whereas art is usually too unruly and ephemeral to be left out in the rain or in direct sunlight. Architecture has permanency; art doesn’t last.

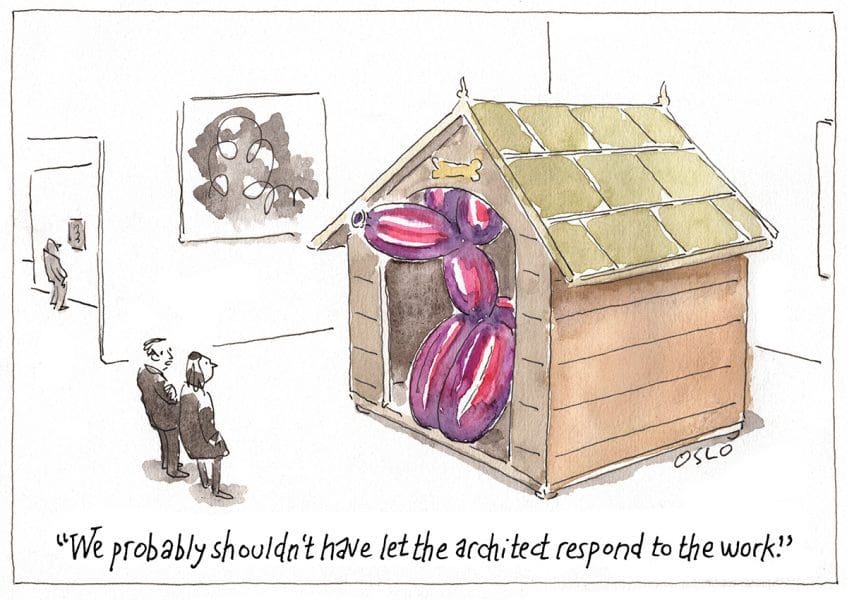

Of course, like most things you think when you’re a teenager, I was hopelessly wrong. Contemporary art is like a virus that needs new hosts to multiply and spread through culture. Sometime around 1977, when Charles Jencks conjoined recent developments in art and architecture into a vision of a whole new cultural paradigm, these two distant cultural cousins started to look like the unwitting hosts of an incubating cultural larvae – postmodernism. And so it was pretty much downhill [or uphill, depending on your view] from there. Art and architecture started to enjoy a newly rekindled close and intimate relationship.

The meeting of art and architecture probably looked like a good and potentially profitable idea too. Where once art could be bought and placed in a forecourt, there were the exciting possibilities of commissioning artists to come up with site-specific works that would be installed before the building was even finished. No one really has the time to stop and look at this art but it’s nice to know it’s there and it doesn’t have to stay there forever – murals can be painted over, sculptures can be craned out and video monitors switched to Sky News. Meanwhile, architecture has forsaken permanency for the hurried rebuild. In Sydney, not even heritage sand- stone guarantees survival and any architectural style that’s out of fashion is doomed.

Although my full appreciation of domestic scale architecture is based on watching many years of Grand Designs and Grand Designs Australia [and one accidental viewing of Grand Designs New Zealand] I still get the distinct impression that contemporary art in these environments is an afterthought for the commissioning home owner and the architect. Someone will occasionally ask for a grand statement bookcase or audaciously scaled home cinema, but I’ve yet to see an episode where someone asks for a gallery-style environment for their Bill Hensons.

Yet despite this tragically degraded existence for art and architecture, I still feel the same kind of Aspergerish interest in artists making art about architecture.

It feels cool and smart, like skivvy-wearing people getting together to drink vodkatinis in a revolving restaurant, or mid-century modern Danish furniture with just the right lamp, there’s an aesthetic equivalence with painters making pictures of swimming pools and Frank Lloyd Wright gazebos, or meticulous scale models of the Farnsworth House, except on fire or something.

The power relationship between art and architecture is the one thing that will always keep them apart.

Art, even at huge scale, is usually the work of an artist and lots of assistants, planners and tradespeople. Architecture, on the other hand is, even if for far less time in the past, a city shaping enterprise that employs thousands of people to build it, hundreds of millions of dollars to make it a reality, and a ton of politics to get it approved. I think it’s a cautionary lesson that when the Third Reich collapsed the person who stepped forward to take over was an architect, not an artist. They are can-do people. Despite the fact that artists had traditionally been people who could design a city or a subway system just as easily as knocking out an oil painting, in the post- post modernist world, they tend to be people who take no for answer.