Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

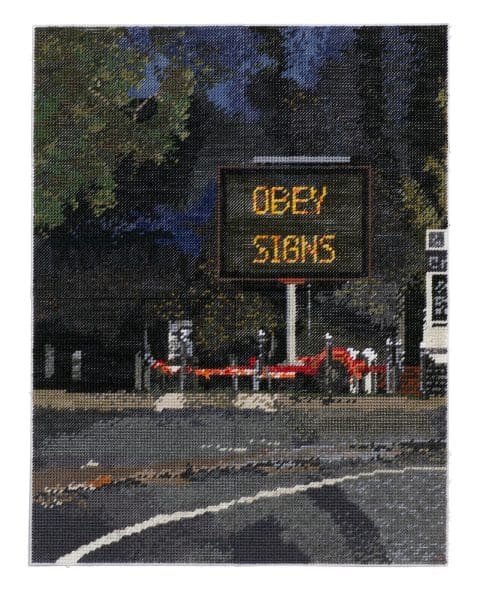

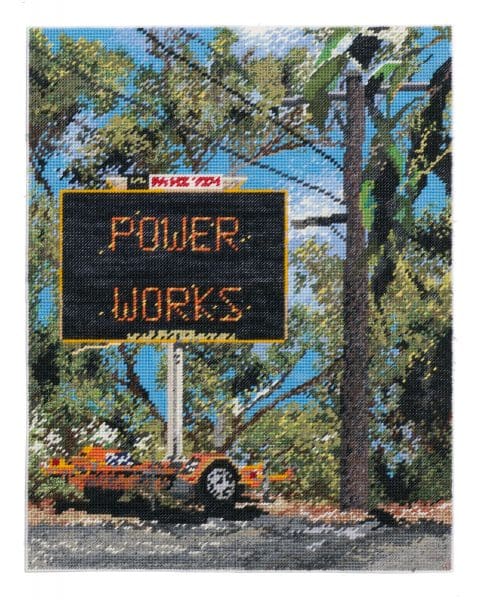

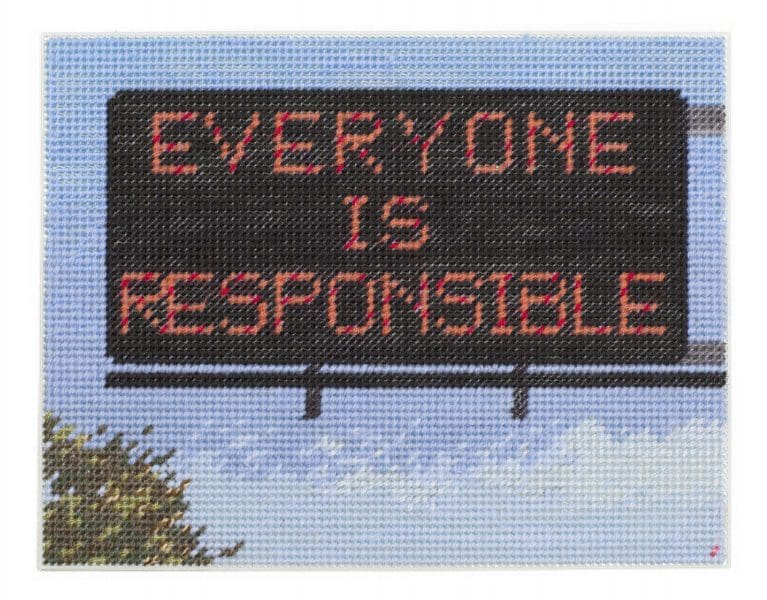

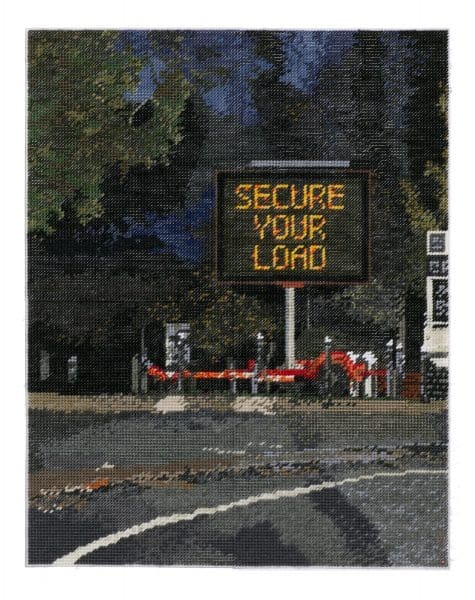

Michelle Hamer’s embroidery-based practice is a meditation on language that captures moments in our collective experience. So far 2020 (a year riddled with difficult, contradictory and overwhelming phraseology: lockdown, hotspot, social bubble, the curve) has given Hamer plenty to work with. Nadiah Abdulrahim spoke to the artist about the challenges of 2020, the dark humour inherent in her work, and her two upcoming solo exhibitions.

Nadiah Abdulrahim: What has this year been like for you, both personally and as an artist?

Michelle Hamer: The fear, grief and uncertainty that people around the globe are going through is familiar to me, because I have dealt with some long-term under-diagnosed health issues and I’ve had periods of isolation and know those feelings. It’s been very interesting to watch the world experience something that has been, prior to this, a very personal experience.

I had a really big year planned – four solo shows, and a residency in Poland, where I had planned to research family history and a connection to the textile industry in Łódź.

And then suddenly the year and everything just imploded. No one knew what was going on, everything got cancelled or postponed, and after a bit of an initial grief, I thought, ‘Well, what do I do with this?’

NA: A new body of work, it turns out. Can you talk about the work you’ve created in lockdown: 2020 is Cancelled? [at Warrnambool Art Gallery (WAG) until 21 February].

MH: I keep lists of language, and at the start of Covid-19 I was noting down some of the things global leaders were saying. It ranged from the outrageous to the banal with some necessary messaging in between. After accumulating a mass of text, I thought I needed to work out a way to navigate it all.

I started making and posting the pieces online and the Warrnambool Art Gallery got in touch. WAG is known for including social issues in their curatorial program and they saw this as an opportunity to acquire and exhibit something current and active. It all happened quite quickly, and obviously it was unexpected because I had not planned on making this body of work.

NA: How long will you keep working on this series?

MH: It’s a bit hard to say. So long as it’s active in our lives, I have to keep it up. I’m being exposed to so much more language all the time.

NA: You mentioned people sending you images – where are these coming from?

MH: From early on during the pandemic people started sending me images of signs they had seen near them, knowing my previous work and that I’m interested in the signs and language around us. I had been collecting and photographing images here – we always seem to have lots in Melbourne – but then I started getting pictures coming in from the US, the UK and beyond. It’s been a really lovely thing to feel that people are connecting with my practice.

So much of what’s interesting to me about the language around us is what we take for granted and yet are absorbing. So even if people are noticing the language because they’re noticing it for me, they’re still noticing it – they’re taking the time to take a photo and send or tag me in it. I really appreciate that.

NA: You’ve turned some of your work from 2020 into GIFs. This particular type of language lends itself well to the GIF format – a lot of it is so contradictory and makes no sense. There’s inadvertent humour in them.

MH: Absolutely. For me, so much about my work is what makes me laugh. I’ve got a dark sense of humour and this language is both deadly serious and extremely funny to me at the same time.

The slogans and statements we are hearing from many of our leaders can be very contradictory, particularly when taken out of context, and that highlights and confounds exactly what has been going on. There’s so much confusion. There are so many mixed messages. And to me that’s the underlying problem – and also why they are funny – because they are being used in real life as instructions and directions, and are supposed to mean something to us. When you apply a critical filter they can be confusing to break down into something authentic.

I’ve become increasingly interested in GIFs within my work, and particularly the ability to go between the manual and the digital. I love the idea of the capturing of contemporary culture through the rapid sharing of information, and GIFs allow me to put the language I’ve been recording and exploring back into the world in a way that anyone can access and share.

NA: Language has always been a central part of your work. What is it about language that interests you?

MH: I’m not sure if I remember there being a time where I wasn’t interested in language – I think I always have been. I read a lot as a child, and I remember reading Alice in Wonderland and being blown away by the made-up words, and books like The Little Prince, seeing the subtleties and interplay between what a drawing can do and what language can do.

I’ve probably always been interested in language, but I think it’s through making and interacting with it that I’ve really come to appreciate it a lot more, and realise how much it’s embedded in everything, and how fundamental it is to the way we communicate.

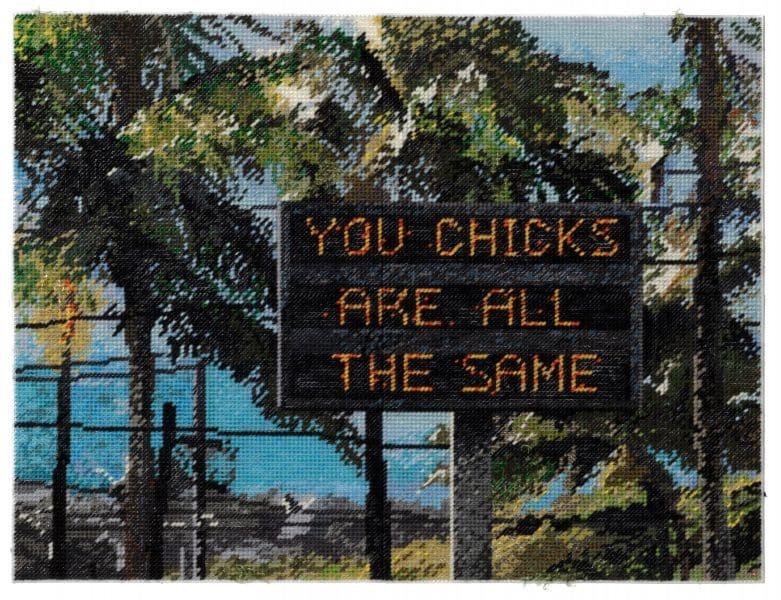

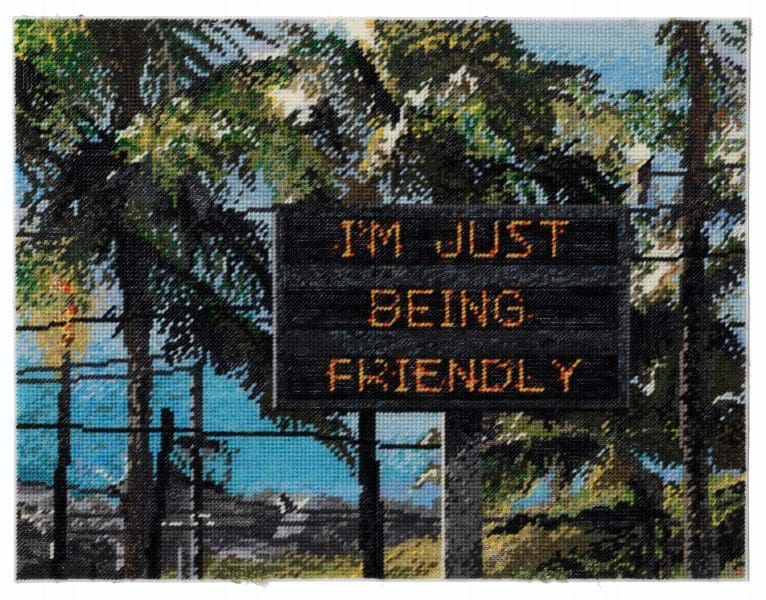

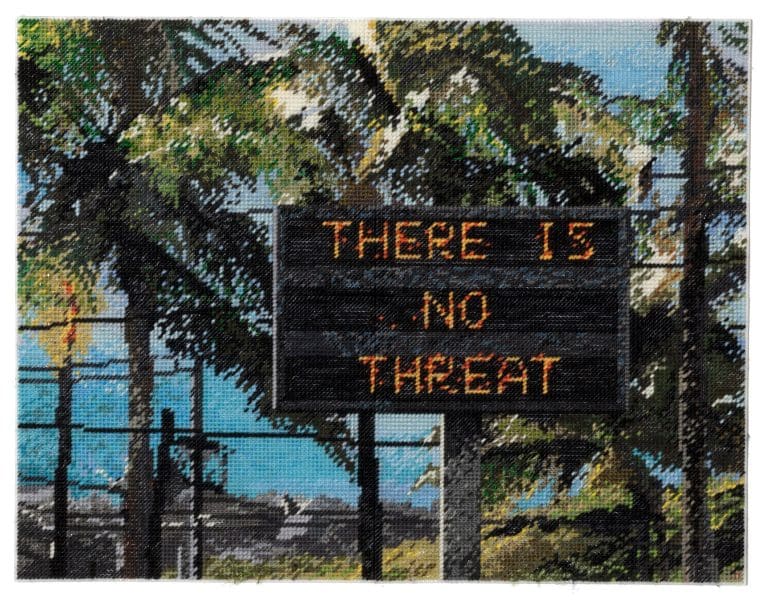

NA: Can you talk about Are You Having a Good Night? [at Fremantle Arts Centre, until 22 November 2020], and how this body of work came about?

MH: In 2018 I was awarded a residency at the Millay Colony for the Arts in upstate New York. In my application I said I was interested in exploring threatening language within the environment, particularly towards women.

This series was actually sparked by a ballistic missile incident in Hawaii [on 13 January 2018] that turned out to be a false alarm. There was a scare, they announced the missile threat, and then had to retract it. There was a sign that said ‘there is no threat’, and when I saw that photo I was so struck by it because I’d already been exploring this idea about threats and threatening language in my work and this [recalled] the sort of gaslighting that women are faced with all the time.

NA: Has it been therapeutic to spend all this time working on this language?

MH: Definitely. It’s a compulsion to make and to record language. To sit and stitch it is the most relaxing and therapeutic part. The best part of my practice is when I get to actually make – I feel like I get to think about the work, be present with it and have some space with it.

This article was first published in September 2020.

2020 is Cancelled?

Michelle Hamer

Warrnambool Art Gallery (WAG)

14 November – 21 February 2021

Are You Having a Good Night?

Michelle Hamer

Fremantle Arts Centre

26 September – 22 November