Mia Boe has always been fascinated by the way art conveys meaning. Her paintings of human figures are striking and politically charged for how they expose concealed histories of First Nations people and the ongoing atrocities of colonialism. Informed by her Butchulla and Burmese ancestry, Boe’s paintings also reference 20th-century art movements, most explicitly social realism and surrealism. And while her work is impressive in its own right, it’s significant that she’s a self-taught artist who only began painting full-time in 2020.

Raised in Meanjin (Brisbane) and based in Naarm (Melbourne) since 2021, Boe first studied fine arts, before realising this wasn’t the path for her. “I just felt like I wasn’t really learning about the things that I wanted to learn about—so, I dropped out,” says Boe. Determined to understand her attraction to art, Boe sought advice from her local arts community and then studied art history at the University of Queensland. “I’m very grateful I chose this route because I feel like it’s provided such a base for my work.”

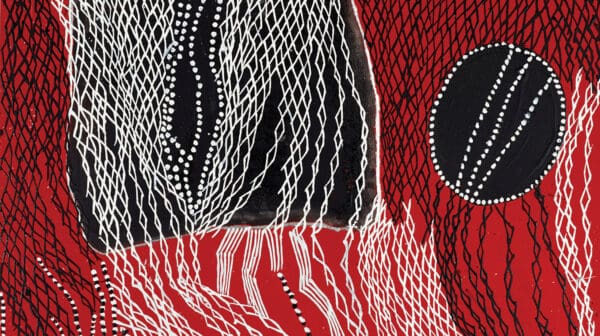

While growing up, the opportunity to see work by contemporary Aboriginal artists was deeply illuminating for Boe, who is influenced by Vernon Ah Kee, Richard Bell, Gordon Bennett, Fiona Foley and Judy Watson. “These artists had a big impact on me as I knew I wanted my paintings to have a verbally political message to them.”

With narrative-driven paintings, Boe’s works are deeply researched to contend with her fragmented understanding of her Butchulla and Burmese culture due to colonisation and political conflict. Boe’s father arrived in Australia from Burma as a refugee when he was five years old, and Boe’s mother didn’t grow up on Country, K’gari (Fraser Island), and wasn’t aware of her Aboriginality until she was a teenager. Boe’s grandmother understandably feared government authorities would forcibly remove her children if their heritage was known. The magnitude of such intergenerational trauma cannot be overstated when it comes to how Boe approaches her art.

When reflecting on how these inherited experiences influence her understanding of self and her relation to ‘home’, Boe quotes the Russian-American artist and writer Svetlana Boym who defines nostalgia as being “A longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed.” As Boe explains, “I’ve created works around this idea that I have a connection to specific places, but they are locations that I don’t have a lived experience with, yet I’ve got these stories and ideas of what that connection could have been—like an alternate reality.”

It was only while working toward her first solo exhibition in 2021 that Boe discovered her great, great uncle, Wonamutta (Jack Noble), was a member of the Queensland Native Police. Wonamutta was abducted from his home in K’gari when he was 14 years old and forced into working as a police trooper as a means of survival. It was Wonamutta’s involvement in the widely reported arrest of Ned Kelly that enabled Boe to access such information in comparison to other ancestors. The artist emphasised the irony of this in her exhibition title, Black Devil, alluding to Kelly’s description of the Native Police as “little black devils”.

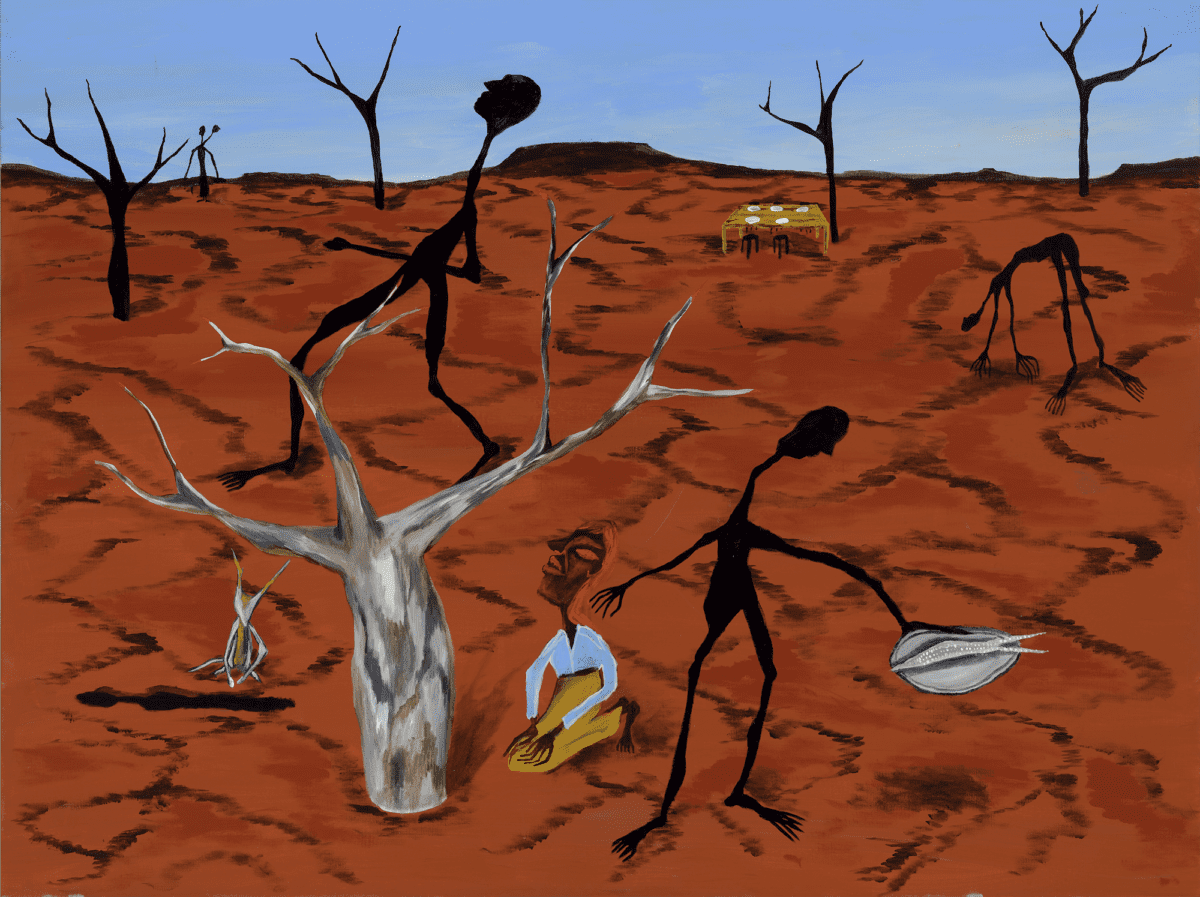

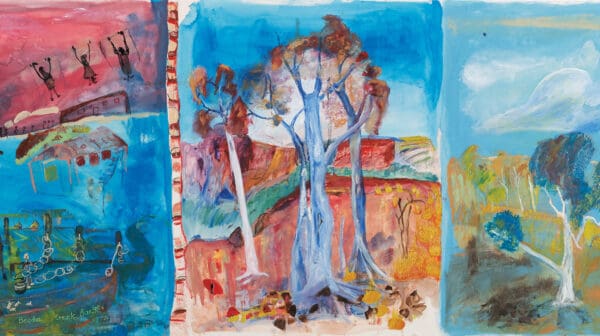

Boe’s compositions of vibrant colours frequently depict elongated blackened silhouettes of Aboriginal people with an emphasis on outstretched hands and defined toes and feet creating an impacting sense of movement. This style purposely evokes the work of settler painters such as Russell Drysdale and Sidney Nolan, complicating the visual record of how Aboriginal people have been portrayed and erased from both history and art history alike.

When I speak with Boe she’s busy finalising a mural to accompany her series, For the Angels in Paradise, 2022, for the National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) Melbourne Now. Boe has produced nine large paintings after being granted access to the NGV’s permanent collection and selected work from Noel Counihan to be exhibited alongside her paintings. “I wanted to respond to Counihan’s hardcore anarchist, communist and activist work and insert myself in the tradition of social realism depicting contemporary issues between First Nations people and the police and legal system.”

For her upcoming exhibition at Melbourne’s Sutton Gallery, Boe will continue to demystify racial stereotypes of First Nations people. Her suite of new paintings will be contextualised by being displayed adjacent to works from one of her major influences, Gordon Bennett. Boe will extend Bennett’s explorations of colonial domestic spaces under the pseudonym of ‘John Citizen’—and she’ll continue to challenge Australia’s colonial history and present.

Melbourne Now

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia (Melbourne VIC)

Until 20 August

Portrait23: Identity

National Portrait Gallery (Canberra ACT)

Until 18 June

The Dingo Project: Wongari

Hervey Bay Regional Gallery (Hervey Bay QLD)

Until 21 May

Mia Boe

Sutton Gallery (Melbourne VIC)

24 June—22 July

This article was originally published in the May/June 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.