Cartographies of the heart

Five Acts of Love, a new exhibition at ACCA, maps the space in which memory, intimacy and resistance intersect.

Megan Cope, THE BLAKTISM, 2014, (still). Image courtesy of the artist.

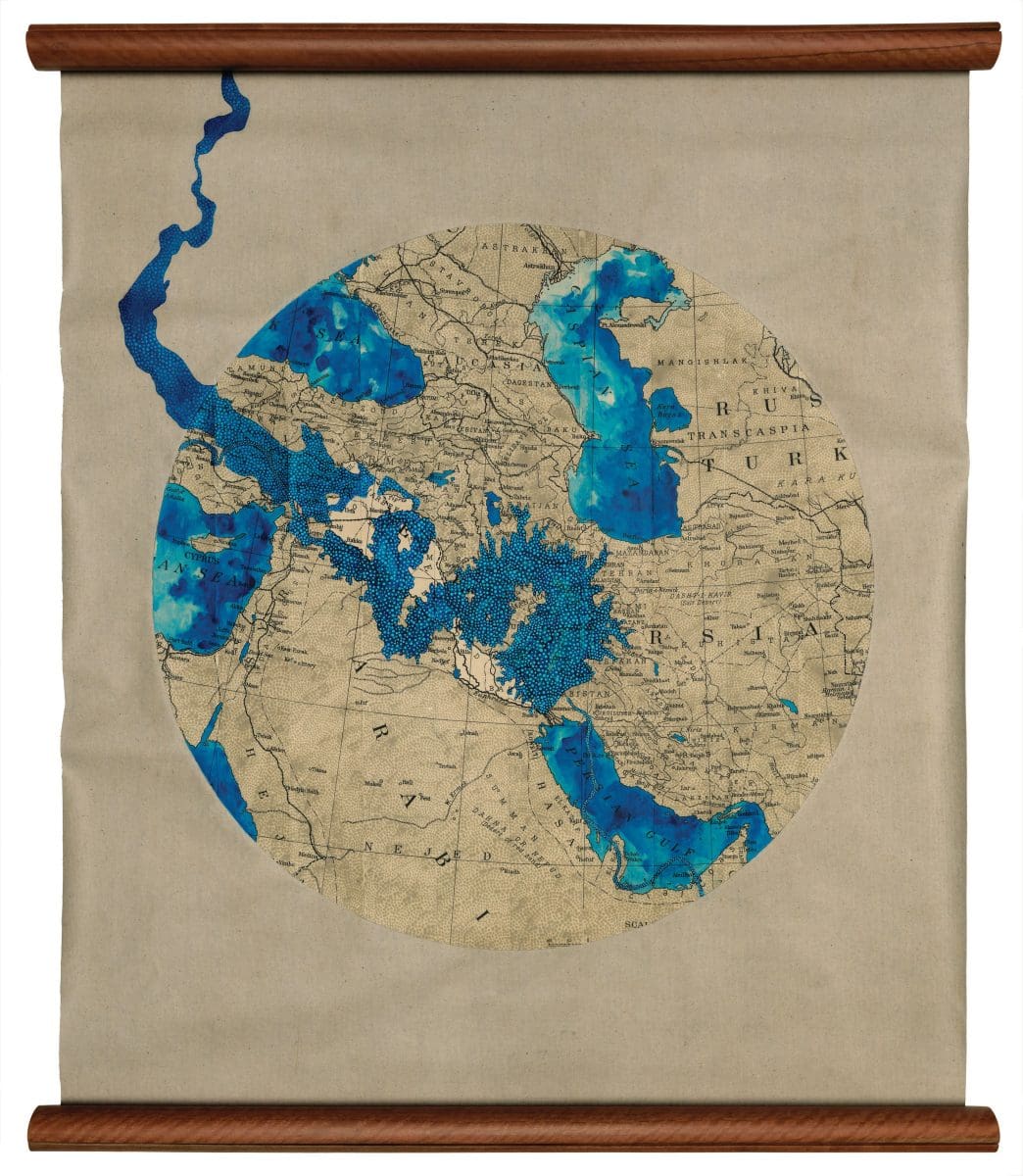

Megan Cope, Flight of Fight #1 Old Rivers, Deep Water, (Lake Qadisiya & Lake Assad), 2018-2019, used engine oil, ink and acrylic on paper and linen, mounter in North Stradbroke Island blue gum. Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial.

Megan Cope, Untitled (Death Song), 2020, drills, oil drums, violin, cello, bass, guitar and piano strings, natural debris, iron thread, metal, rocks, gravels. Stereo sound: Remerciement. Acknowledgment: Hoshio Shinohara. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery (Brisbane).

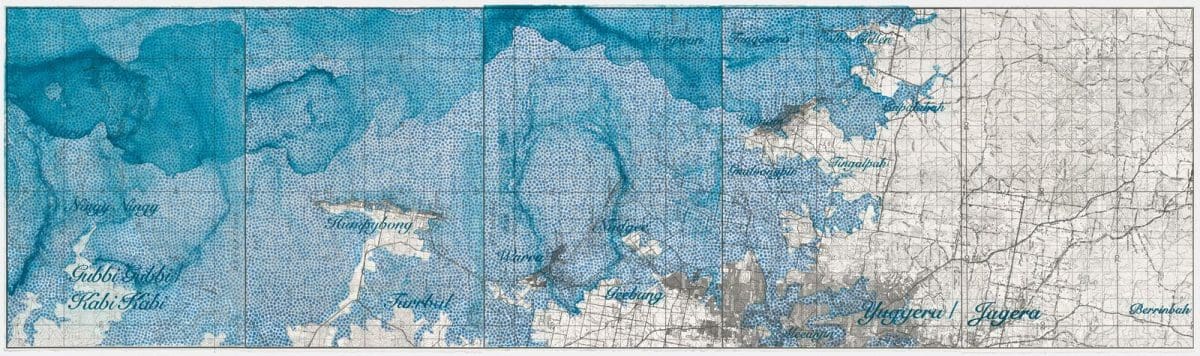

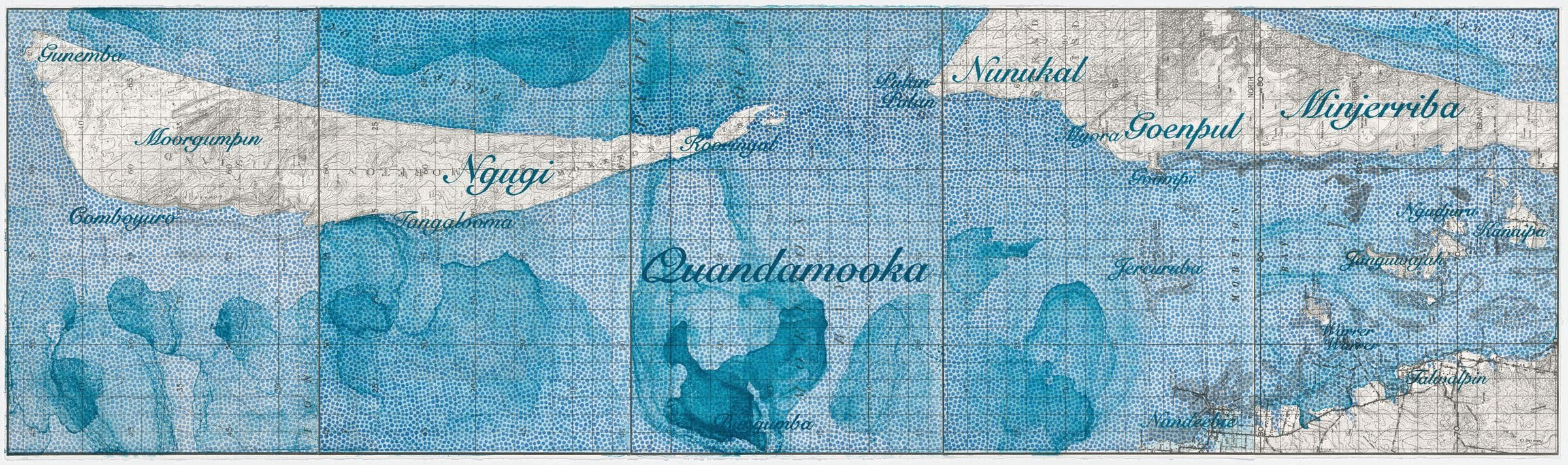

Megan Cope, YARABINDJA BUDJURUNG II, 2021, colour lithograph and photo-lithograph, printed on five sheets, ed.1/5, 105.7x 365.0 cm (image), 106.5x 365.5 cm (sheet). Printed by Martin King at Australian Print Workshop, Melbourne. Co-commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria and the Australian Print Workshop. Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2021. © Megan Cope. Photograph: Matthew Stanton.

The last time I saw Megan Cope was pre-Covid, at the opening of the 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, just as whispers of a pandemic were starting to circulate. For the Biennial, she’d made perhaps her most ambitious work to date, Untitled (Death Song), a sculptural installation constructed of materials related to the mining industry. The sculptures were instruments, with musicians playing a score based on the bird song of bush stone-curlew.

“The bush stone-curlew is very important to our people on Quandamooka Country,” says Cope. “They’re really part of the landscape, like our extended family. We’re tied to them through kinship.” It’s also a messenger for death: with Untitled (Death Song)’s materiality drawing on extractive mining, speaking directly to the environmental throes that the world feels like it’s currently going through.

Cope and I are now sitting down in Melbourne. She’s in town for an opening at the National Gallery of Victoria for New Australian Printmaking—and she’s had a whirlwind couple of months. Untitled (Death Song) is currently exhibiting at Palais De Tokyo in Paris for Reclaim the Earth, and she’s just arrived back in Australia after the opening.

“We had six French musicians, directed by [Australian] Isha Ram Das, to activate the work,” she explains. “They had to learn the instruments, and create a composition based on the death song of the curlew.” The French musicians had never seen or heard of the native Australian bird before. They were agog when she showed them videos of it on YouTube.

Cope is visibly thrilled when discussing the reception of her work in an international context. Her practice is so specific to the geopolitical and colonial contexts of Australia—yet its resonance goes well beyond the unique context of Australia, speaking to universal themes.

“Seeing my work there, it gave me a certain level of confidence and pride. Pride not just in myself, but in the energy and survival and the power of our people and Country. I believe so strongly in that.” France is going through its own colonial reckoning, as well as navigating a world on the edge of climate collapse: in this context Cope’s work, which is ultimately rooted in Quandamooka ways of listening to the world around us, clearly resonates.

Yet 2022 has been difficult for the artist. In the lead up to the Paris exhibition she lost her studio in the recent Lismore floods, unsure if she’d be able to make it overseas. “I was cleaning up mud still, I couldn’t find my passport,” she remembers. “Then there was another flood.” The climate catastrophe playing out in Lismore has prompted a turning point in her practice.

“My whole life depended on that studio,” she says. She’d been in Lismore for just two years before it was lost. She’d arrived there when Covid kicked off, hunkering down in a granny flat behind artist Karla Dickens’s house. She loved it so much she decided to stay long-term.

Cope has lost materials and tools that she’s collected over 20 years to make much of her work, as well as archival research and documents. The reality is she doesn’t have the set-up to make the same large-scale sculptures she’s previously made—but this period is a turning point.

“I’m being philosophical about it. Everything happens for a reason,” she says. She will set up a studio again, but back home on Quandamooka country. “My time on Bundjalung country has finished. It kept me productive and safe and well. But if you’re gonna start again, you need to do it somewhere you’ll never have to leave. My family is like, ‘Come home now’.”

While she’s lost many of her tools and materials, Cope has adapted, beginning a series of what she calls “living sculptures”.

A prototype Kinyigarra Guwinyanba was shown at Milani Gallery earlier this year. They’re oysters that have attached themselves to wooden poles, collected from listening to the shifting tides of the ocean. “To attract oysters you need some empty oyster shells—they like to grow on their ancestors, they like to be in clusters.”

An iteration of this work will be shown in Korea at the Busan Biennale. Meanwhile she’s also exhibiting a new body of work at Shepparton Art Museum for Art in Conflict, and is showing in the group exhibitions Agent Bodies at RMIT Gallery and Embodied Knowledge at Queensland Art Gallery.

Back in Melbourne we head to the opening of New Australian Printmaking (where Cope is one of four exhibiting artists alongside Patricia Piccinini, Shaun Gladwell and Tim Maguire). It includes the largest print work she’s ever made: a three-metre cartographic work titled YARABINDJA BUDJURUNG I. It shows Quandamooka country with a seven-metre level rise of water, and is part of a series she’s been making since 2009, named After the Flood.

We chuckle at the title of the series—it describes where she’s at in her life now. After the Lismore floods, she says her life and practice still feel full of possibilities.

New Australian Printmaking

Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

Until 11 September

Embodied Knowledge

Queensland Art Gallery

13 August—23 January 2023

This article was originally published in the July/August 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.