Reframing a Collection

Drawn from the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art at the University of Western Australia (UWA), Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery’s show Place Makers, reframes the artists—who just happen to be female.

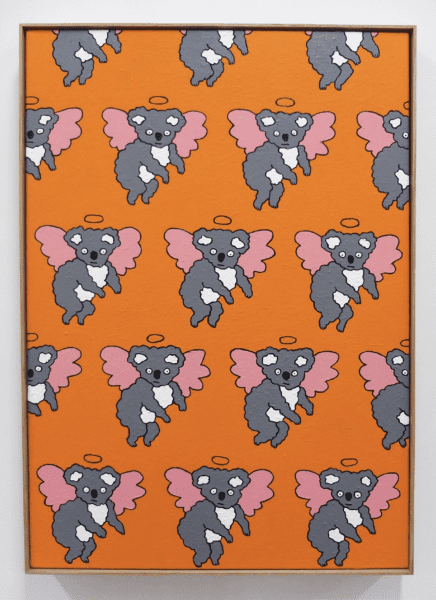

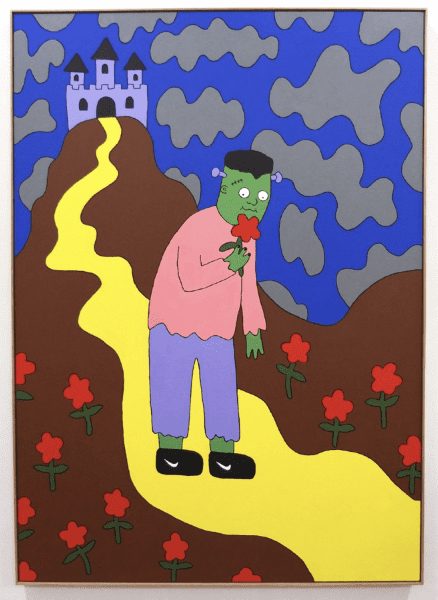

Matthew Harris, Ascension, 2021, acrylic on canvas 91 x 61 cm framed. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Pompom.

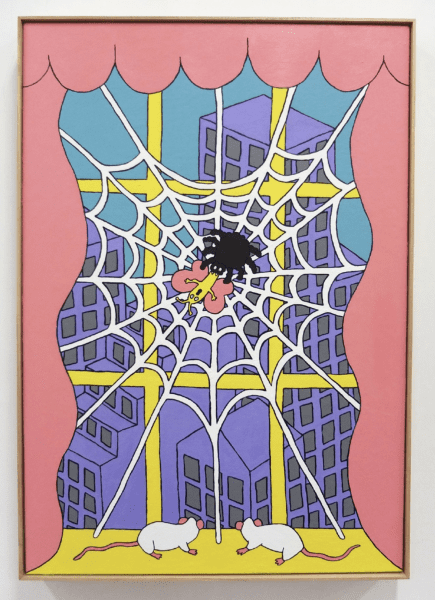

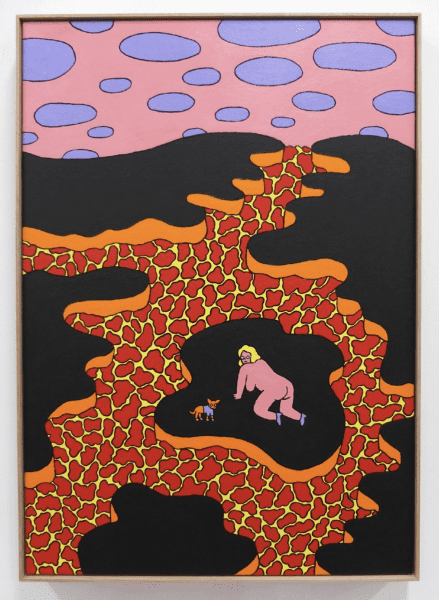

Matthew Harris, Moon river, 2021, acrylic on canvas 91 x 61 cm framed. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Pompom.

Matthew Harris, Billionaires row, 2020, acrylic on canvas 91 x 61 cm framed. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Pompom.

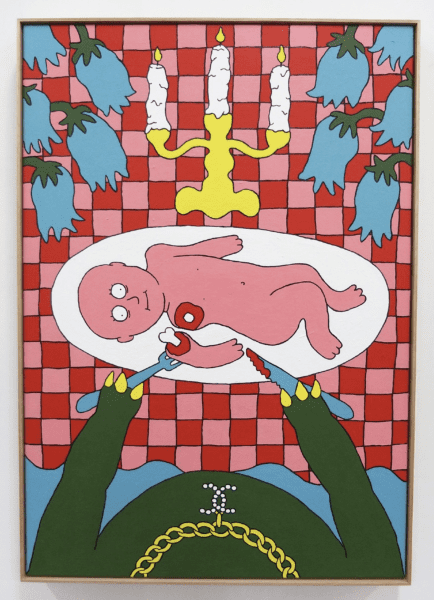

Matthew Harris, That’s hot, 2020, acrylic on canvas 91 x 61 cm framed. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Pompom.

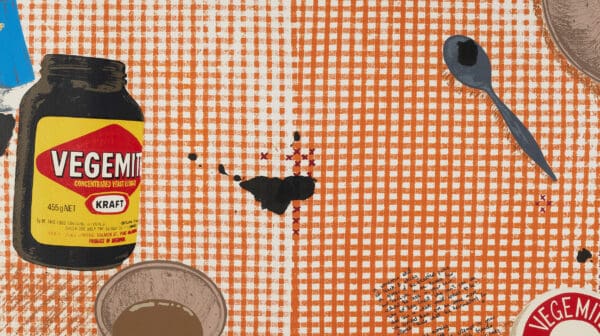

Matthew Harris, Perspective, 2020, acrylic on canvas 162 x 122 cm framed. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Pompom.

From repetitions of flowers to grim reapers riding unicorns to cartoon devils gleefully inflicting pain on their enemies, the paintings of Matthew Harris hang between amusing and provoking; the cute and the uncanny; the absurd and the vulgar. Painted in a flattened yet buoyant style, Harris’s work finds easy company in camp aesthetics – yet as much as he celebrates ‘bad taste’ and naughtiness, his works are also highly thoughtful, at times shedding hints of sentimentality.

Tiarney Miekus spoke to Harris about where his camp aesthetic comes from, questions of taste and class, thoughts on Jeff Koons and Agnes Martin, and how his new show The Simple Life is influenced by the 2000s TV show of the same title, starring Paris Hilton.

Tiarney Miekus: The camp aesthetic of your work is often commented on, and I’m curious if it’s something you’ve explicitly tried to conjure?

Matthew Harris: I’ve never been camping in my life [laughs]. I don’t try to conjure camp explicitly, it just happens. It’s mostly a sense of humour and trying to bring various references into the work. And to f*%k everything up, make it a little bit less perfect and show that there are all sorts of ways of being and doing things.

I think most people tend to think of it [camp] as being colourful, kitsch and fun. I don’t know about that. Maybe it’s just being a bit over the top. Exaggeration, and maybe some vulgarity as well.

TM: The writer Zadie Smith has written that camp comes out of a lack – whether cultural or financial – and is about flaunting and making something good of this lack. Is that something you identify with?

MH: I think that makes sense. I grew up pretty much in poverty in the country, in Wangaratta. I was a goth as a teenager, and I came into art through the local punk community. It was slightly more socially acceptable to be goth than to be queer in a tiny country town. I can’t step off the train there without being called a faggot, it’s pretty rough.

I grew up around a lot of tacky imagery as well, and lower socioeconomic decorations. There’s something nice about that. Also, I was always a really quiet person, and I guess being interested in art was easier than talking to people. Art brings all of that together.

TM: I read that you didn’t go to art school of any kind?

MH: No, nothing. I dropped out of high school in year 11. I was too busy doing my hair to think about school [laughs]. I had some crappy jobs or was on the dole, and lots of walking.

TM: How did your art practice start then?

MH: At first I was working with everything but painting: a lot of ready-made objects, videos, photos. I started out in photos, but then I got sick of using only things that already existed. I wanted to work with imagery that wasn’t already there.

Painting sort of started as a joke, because I really didn’t like it for a long time, but it’s growing on me. I thought if stupid colourful paintings are what people want, then that’s what they’ll get! But they’ll be so stupid and so colourful that something interesting happens.

TM: When you started painting five years ago, were the works similar to what they are now?

MH: Exactly the same. I can’t really do any better. They’ve always been really simple: flat colour, basic outlines, very lumpy, and always the same size, which I got from standard $2 shop canvases. Now the canvases are horribly expensive and made to fit that format. It’s so much fancier now. I don’t have to steal paint anymore – what a luxury.

TM: That flattened, cartoon-like style you have, was that quite natural to you?

MH: I don’t really know how it happened. I’ve always drawn in outlines, never scratchy charcoal or anything. No shading. They look like hard-edge abstraction until the very last minute, when the outline goes on. It’s kind of a reversal: starting with filling it in, and then ending with the outline. They look as synthetic as possible.

TM: I know you’re interested in exploiting various ready-made images, whether it’s religious imagery of devils and angels, flowers, grim reapers, or referencing various icons. What draws you to such well-known imagery?

MH: Everyone knows about and can understand those images. They’re all pictorial tropes. The paintings are building a language of their own, using all the different characters to tell different stories. Like there’s one [a picture of a grim reaper on horseback] called Bareback. I did it originally because I remembered the grim reaper AIDS ads from the early 1990s on TV. It was a grim reaper bowling. I just remember it being so scary. But it’s also quite universal, too. It could be anything, really.

TM: But then it’s your instinct to turn that humorous?

MH: Yes, it’s much easier to digest. Cute characters are really good for communicating more difficult things in a way that’s less horrible. Cartoon violence seems less threatening than actual violence.

TM: There’s something that you seem to intuitively get about popular culture, both the narcissism and the glamour. Are you thinking about this when you engage with the world?

MH: I’ve always been more into unpopular culture, but I definitely notice a lot of those things. I love Take Five magazine. Well, I love the covers. There’s always some sensational, terrible story. They’re making magazines out of the worst moments of people’s lives, and it’s all so funny. Like, ‘My family was killed in front of me, but I was saved by this Teddy.’

TM: I can see how that would appeal to you. I notice in your work you also reference artists from Marcel Duchamp to Jeff Koons. Why so?

MH: Everything is fair game. But if you’re wondering what I think of Jeff Koons, I kind of hate him and love him at the same time. He’s an American Psychobusinessman figure, and I don’t like that, but it is pretty funny that he can elevate something so basic to something so prominent and extreme. Archaeologically, his sculptures will last forever. It’s kind of shocking. Stainless steel doesn’t rust or anything. It might get a bit dented, but it will survive. That’s terrifying.

More than Jeff Koons, or any of those people, I really love Agnes Martin. So simple and pared back. And, somehow, she manages to get so much emotion in there using almost nothing at all.

TM: You once said that there’s no such thing as high or low art, and that it’s just a question of taste. Can you expand on that?

MH: I think everything is the same. To me, there’s not really much difference between all the European old masters and Take Five magazine. It’s all colours and tragedy.

TM: So why do we call some things art and others not?

MH: I guess so artists can pay the bills [laughs].

TM: It can’t be your ambition, then, to make great art if all images are the same?

MH: I don’t really know if I’ve ever been ambitious in my life. One of my high school teachers said I’d ‘never go anywhere with that attitude,’ which is still true [laughs].

TM: Can you tell me about the works in The Simple Life?

MH: It’s eight paintings: six regular size, two larger, all in a row. It’s named after the TV show starring Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie. I hate them, but I also love them at the same time. They’re really witty and sweet, not as nasty as I remember. But I’m really not a fan of that excessive material lifestyle. I love [material] things, but having nothing is better. I’m using The Simple Life as a metaphor for real life. In the TV show they were traveling around doing odd jobs that poor people usually have to do, but they’re rich heiresses slumming it, and for me it’s pretty much the opposite.

TM: How does this play out in the paintings?

MH: The show starts with a repeat patten of sperm, because we all start from these tiny little things, and grow up. They have cute little eyelashes, but scary sharp teeth like they’re going to eat their way out. The next painting is a landscape with the ground opening up, where this lady and her Chihuahua – which I painted wearing a sweater and little booties – are trapped on an island. I just can’t stop thinking about the middle of the earth being molten rock. We’re all so precarious, just perched on top of this thin membrane, spinning around.

Another one is a crocodile or lizard person eating a baby. I just can’t stand babies! They’re so annoying. Ban all babies [laughs]. The next painting is Frankenstein going for a walk and sniffing a flower. It’s sad but kind of hopeful. And another painting is koalas. That’s from the big bush fires last year, they came pretty close to my hometown and it was shocking to think about everything dying. So they’re all on their way to heaven, floating up and out of the frame. As white as I turned out, I’m also Koori through my mum’s side. The fires were pretty heartbreaking for her and the rest of my family. It’s important to stay connected to that.

TM: There’s another painting you have in this show of a ghost coming out of the earth, floating among a cosmos of planets.

MH: I’ve done a couple like this before, thinking about how tiny we are, how unimportant, and how in the end it all means nothing anyway. I guess it’s a bit existential and environmental, as well. The show starts up very close-up with the cells and gradually zooms all the way out, and I guess all we can really do is try to have a nice time while we’re here.

The Simple Life

Matthew Harris

Galerie pompom

17 March – 18 April