The notion of a worthy adversary is an ancient tradition. In Classical Greece, kleos (glory) could only be achieved with an audacious death, battling a formidable enemy. In fiction, the feats of 007 and Sherlock Holmes are induced by contests against arch-enemies. Rivalry burnishes innovation and triumph on both sides.

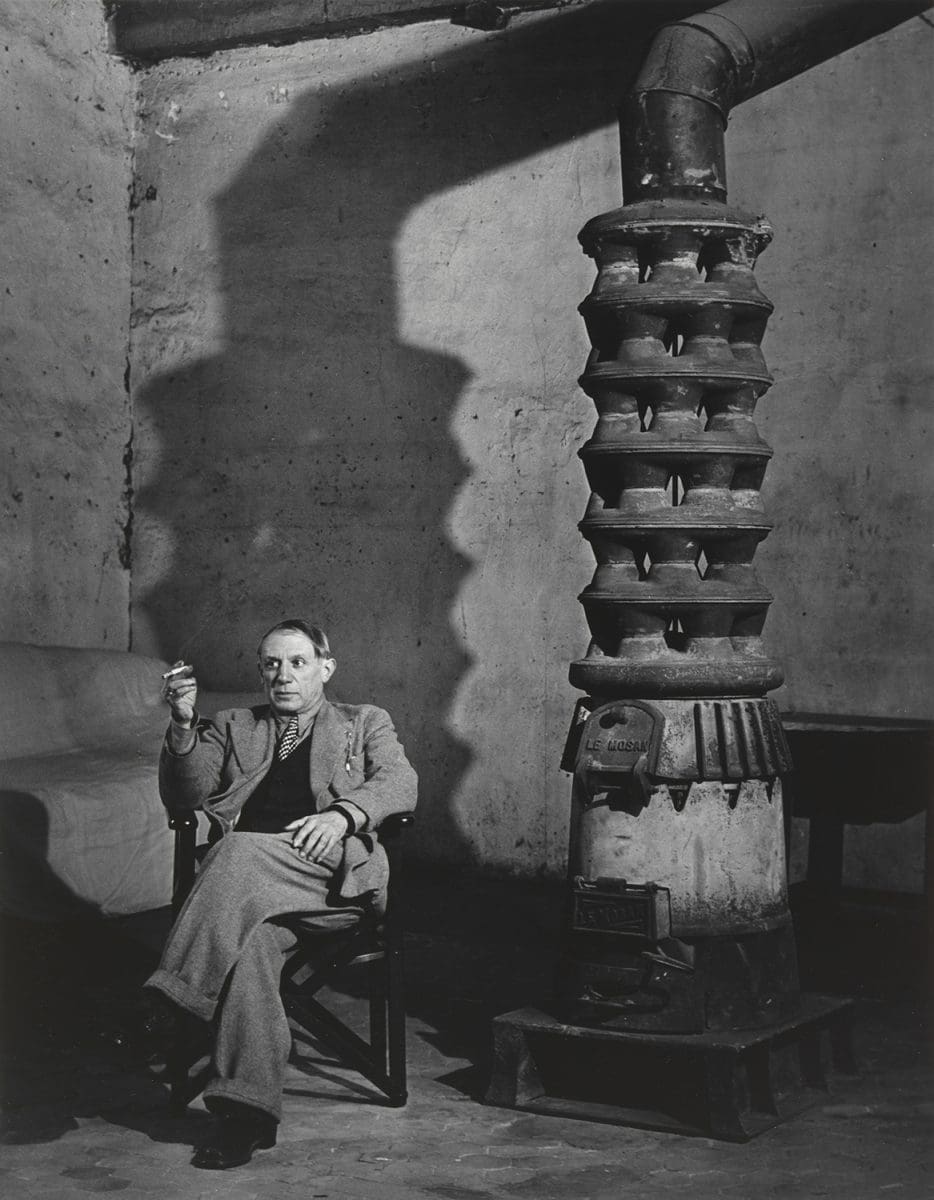

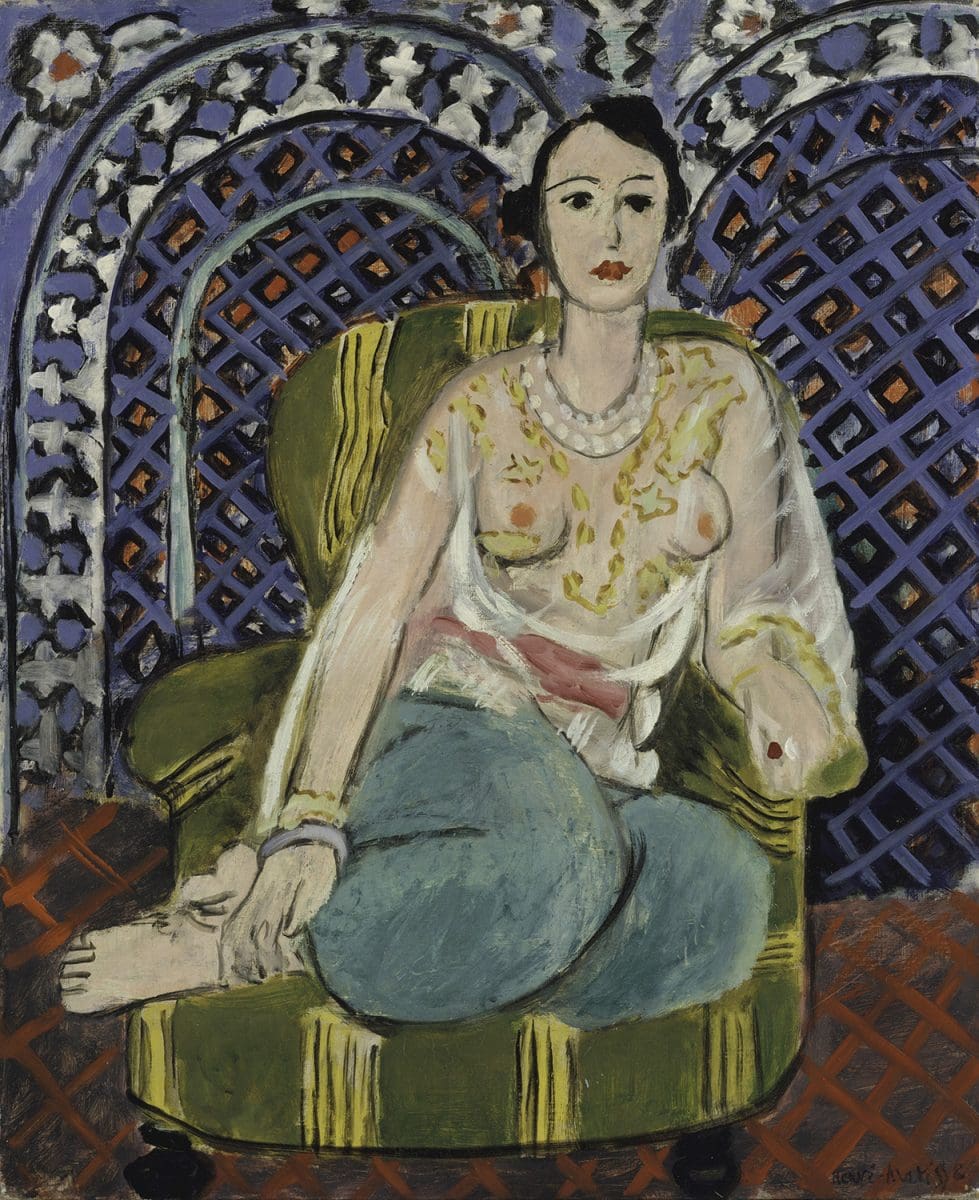

Early 20th-century Paris was an arena for the forging of ‘Modern Art’. Here in 1906, Henri Matisse, the newly-crowned prince of French radicalism, and Pablo Picasso, a fresh, brash Spanish talent, first met and vied for success. “There was an immediate tension,” explains curator Dr Jane Kinsman. “Matisse was known for his brilliant colour and Fauvist vision. Picasso kept popping up with cubism or the infamy of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [1907]. He was a nuisance.” Both worked in the shadow of Paul Cézanne, who died the year they met, leaving room for the next big thing.

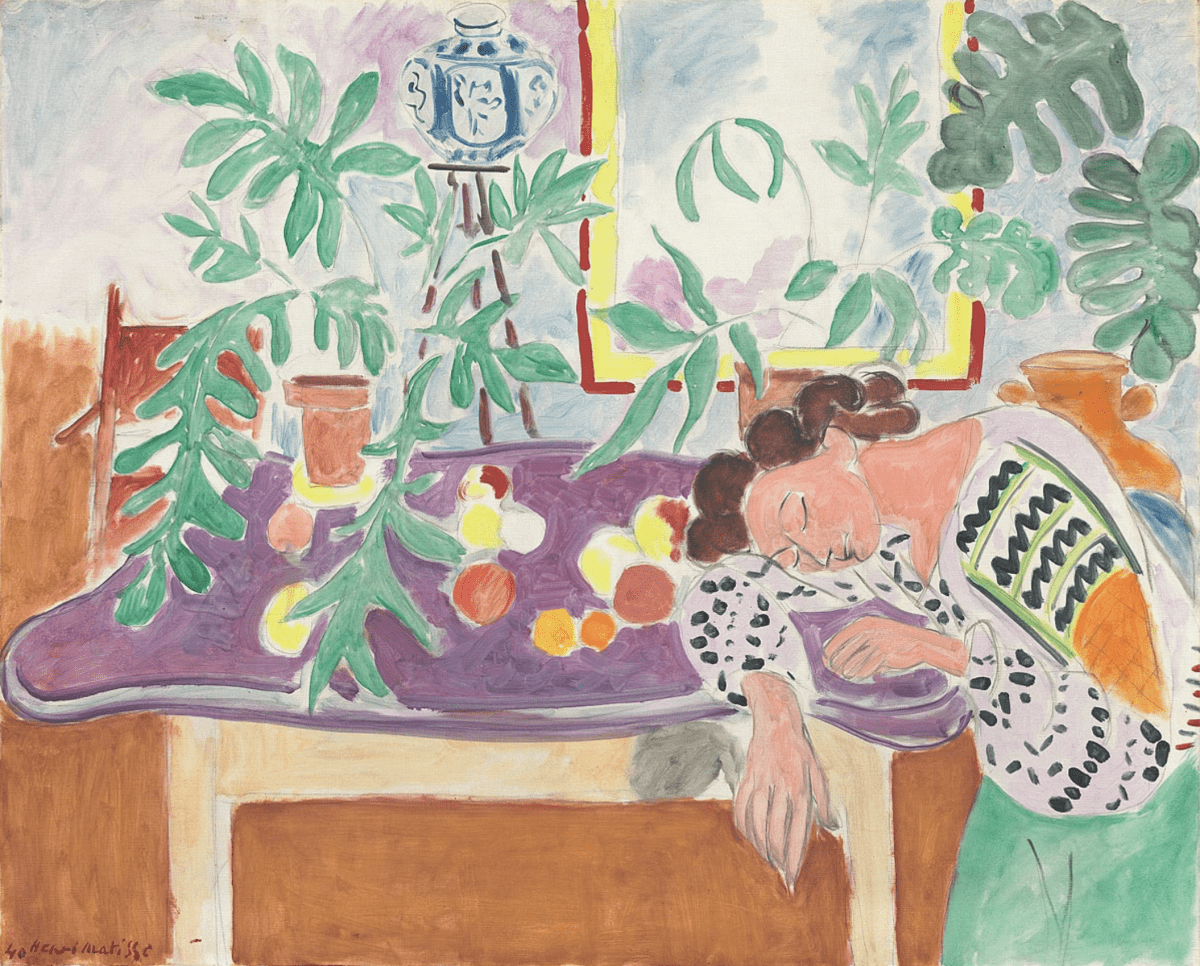

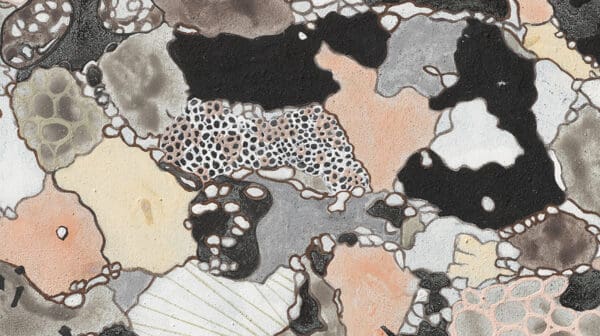

Matisse & Picasso narrates the artists’ intense mutual scrutiny, public disagreement and praise-via-appropriation. “They’re always borrowing: texture, colour, layering and cubist ideas of space pass between them.” Matisse and Picasso’s symbiosis ensured the longevity and posterity of their art. “They needed each other,” reflects Kinsman. In 1912, Matisse painted a bowl of blushing, almost luminous oranges gently lit through a window. Nature morte aux oranges [Still life with oranges] arrives on loan from Musée Picasso. “Picasso acquired it himself: he saw it as the ultimate Matisse painting, though he didn’t say so publicly.”

Half a century of competition ended with Matisse’s death in 1954. The exhibition’s final chapter is eulogistic: “Picasso didn’t go to the funeral, but his painting immediately changed,” says Kinsman. The studio [L’atelier], 1955, on loan from the Tate Collection, shows Picasso’s studio in the south of France, windows thrown open toward a glowing tropical garden. “The bright colour and exotic motifs are a mournful homage to his absent friend and rival.”

Matisse & Picasso

National Gallery of Australia

13 December–13 April 2020

This article was originally published in the November/December 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.