Medium, material and memory converge in Campbelltown Arts Centre’s latest exhibition, in every room, through the work of six artists, pulling together the threads that bind and entangle all of us, in this world.

Socio-political histories and personal storytelling come together in the works of Lara Chamas, Jagath Dheerasekara, Kuba Dorabialski, Roberta Joy Rich, Sancintya Mohini Simpson and Curtis Taylor, artists from all over Australia, who track the past and map the present, showing an inextricable link between catastrophic political events and the current times.

Curated by Isabelle Morgan and Emily Rolfe in collaboration with guest curator Eddie Abd, in every room has a mix of new commissions and existing works. The show is presented over six spaces and opens with a youth space for children and young people promoting an engagement with the themes and subject matter of the exhibition, through relevant books, media and listening materials. The space is aimed at providing young minds with resources to deepen their understanding of the histories and provocations in the show.

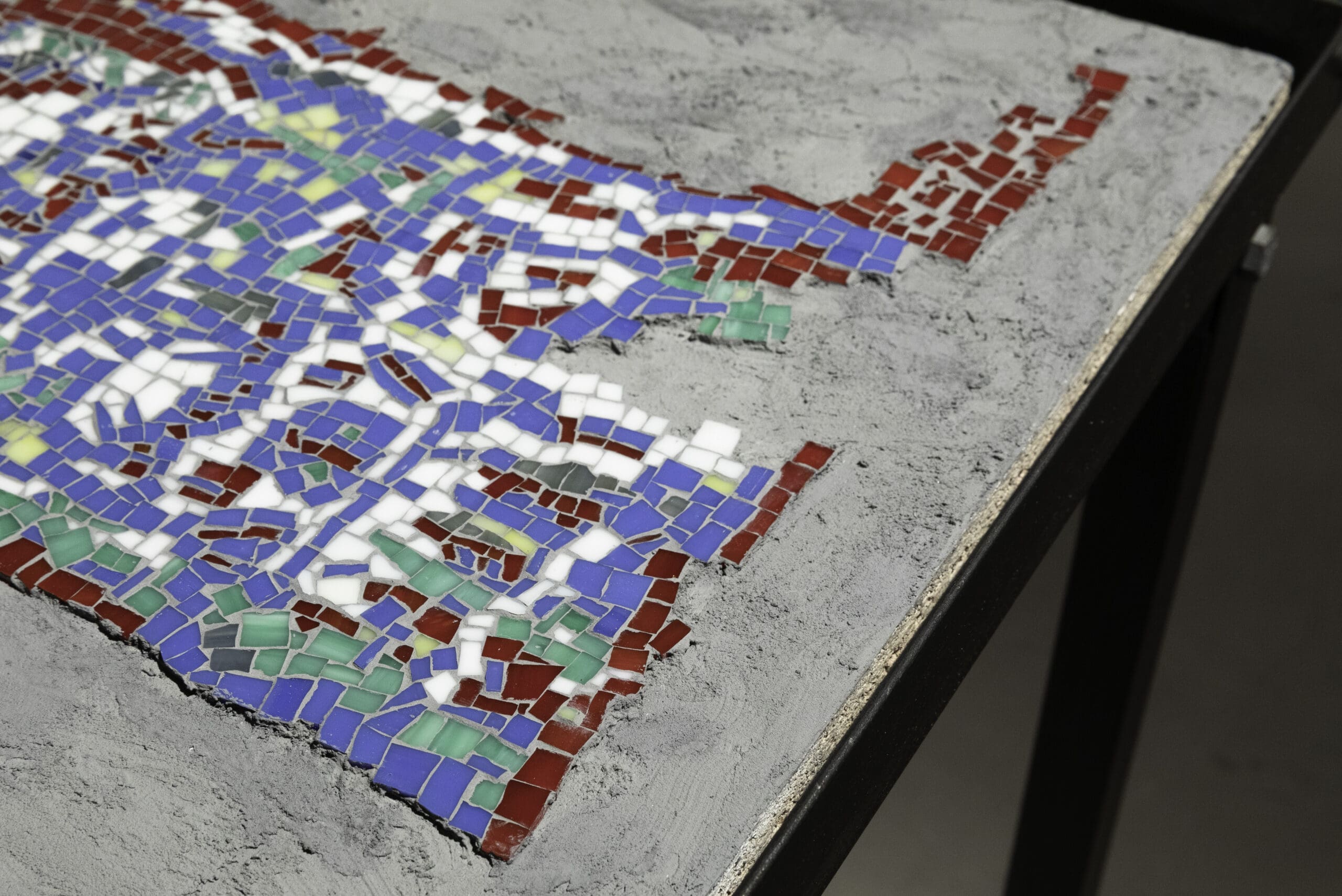

Right after the youth space is Lara Chamas’ Dawa Ahmar دواء أحمر (2025), which translates to Red Medicine, and uses glass, betadine, grout, steel, and concrete, among other materials. Chamas has recreated sections of her grandmother’s prayer mat in mosaic, hand cutting each piece of glass and setting them out, at times cutting herself in the process.

“I really wanted to embody that sort of repetitive motion of prayer and emulate how many times she would have had to pray on it to wear it down to the ground,” says Chamas.

She adds that the meditative nature of doing something over and over again was a way for her to channel the pain, history and memories of her ancestors. The work references her personal familial loss due to the ongoing bombardments of Lebanon since October 7 2023, but also the historical traumas that her grandparents and parents have had to suffer and flee from.

Her use of Betadine, its red colour a mark both of blood and as a healing agent is significant. Beit-ed-dine Palace in Lebanon is a UNESCO-protected site and museum for Byzantine mosaics. The connections and alignments surfaced as Chamas researched and conceptualised this work.

“Medium has meaning to me. It’s a big reason why I make sculptural installation. Different mediums or materials have…an energy. So, it felt very important to use the Betadine as is and not some sort of false version of it,” she says.

“Similarly, with glass, concrete and metal … these being the main debris after airstrikes.”

Piecing together history and making art in the current context when multiple genocides are being livestreamed to our phones is something that makes Chamas pause.

“When I was curated into the show, I thought [about] whether to take it or not, and whether art has a place right now, whether I could live with myself making art right now.”

“But I also feel a personal and cultural responsibility to my lineage, to try to preserve something. To preserve this loss. It feels like I’m channelling or trying to pay respect to this bloodline, this thread,” she adds.

It is this same honouring of ancestral suffering and cultural narratives that Roberta Joy Rich presents through her work !Norasa Khâimâ: Aiho Aboxan “Dawid Stuurman” (2025) which is a KhoiKhoi language phrase translating to Unbound Resistance: Remembering Ancestor “David Stuurman”.

Rich illuminates the story of David Stuurman, a South African KhoiKhoi chief who was banished to NSW as a convict. Throughout his imprisonment, he held tenaciously on to his dream of returning to his country, something that never happened for him.

The commissioning for this work came at a time of great personal loss for Rich—the passing away of her father.

“There was this quite intense duality of wanting to explore my grief and channel my energy of grief into my art. But I was also thinking a lot about the collective mourning that we’re all experiencing globally with the genocides that are occurring in many places,” says Rich.

“I wanted to create a space for a kind of collective mourning, and so I instantly knew I wanted the space to be quite dark and have these small moments of light.

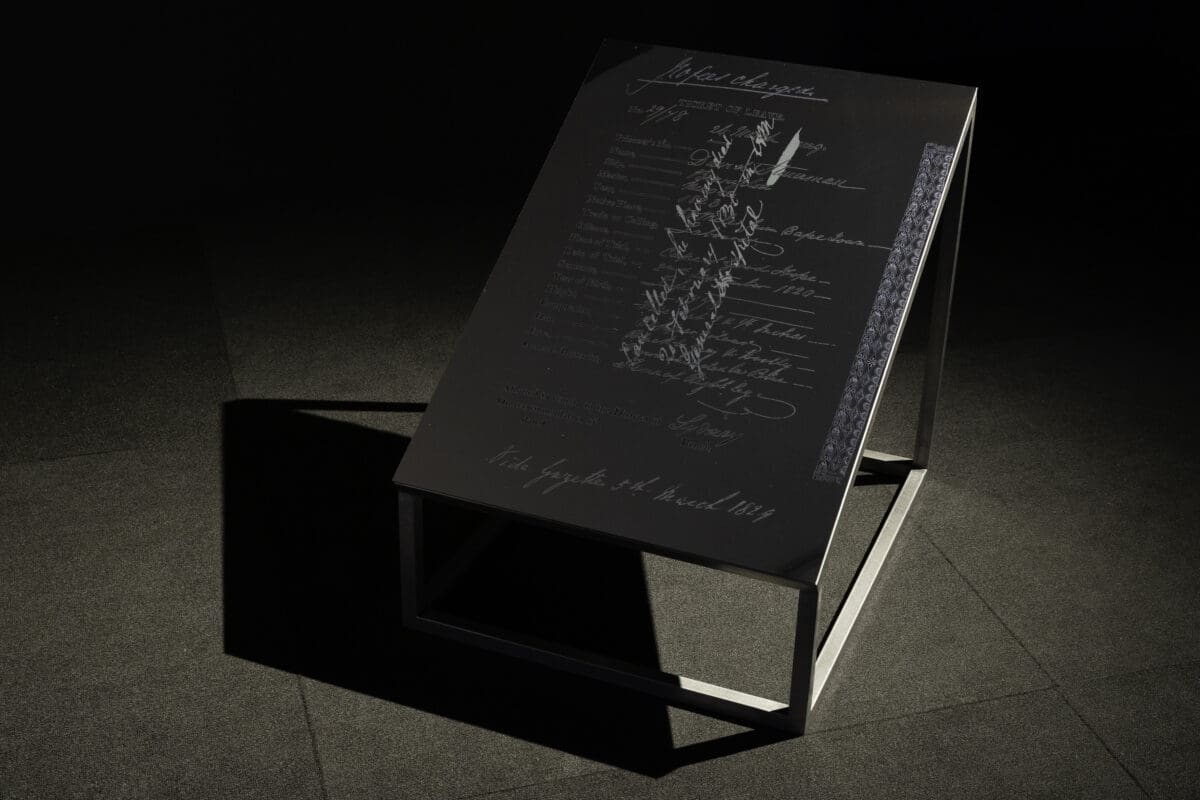

The work is a mixed media, audio, video installation that has a sculptural piece, which is David Stuurman’s Ticket of Leave document printed on aluminium composite material held by a stainless steel frame.

“It’s a kind of like an installation, a pseudo memorial headstone-type sculpture to draw attention to the fact that actually his physical body was unable to return to country.”

An echo of the many lives under rubble and debris, not memorialised by their community and family.

“Artists have the responsibility to share what is happening in the world around them. We reflect the beauty, the despair and the dialogues happening around us. The work that I’m making is inherently connected to the current context of genocidal violence, be it in Palestine, Congo, Sudan, Myanmar, the many places that aren’t always spoken of,” she adds.

in every room

Campbelltown Arts Centre

(Sydney, Dharawal NSW)

Until 14 September