Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

Art museum curators work with works of art: foregrounding their particular qualities, putting works into telling juxtapositions, and revealing contexts. Often this curatorial work is done in dialogue with the artists themselves. But what happens when the emphasis of an exhibition is actual recorded dialogues—interviews—with living artists? When works of art are only part of the mix, rather than the focus?

A current exhibition I’ve curated, Meet the artists: From the James C. Sourris AM Collection of Artist Interviews, now at the State Library of Queensland, features interviews with prominent artists and art figures, undertaken by various curators, academics and arts writers, alongside artwork and reference paraphernalia.

Yet it posed specific curatorial challenges: how to work in an actual gallery setting with filmed interviews usually seen online? How to underscore connections between the artists’ recorded accounts of their lives with their work? The result is multiple screens showing the interviews, with one screening every interview in alphabetical order; and four more highlighting eight selected artists, accompanied by recent works and studio materials proposed by each artist.

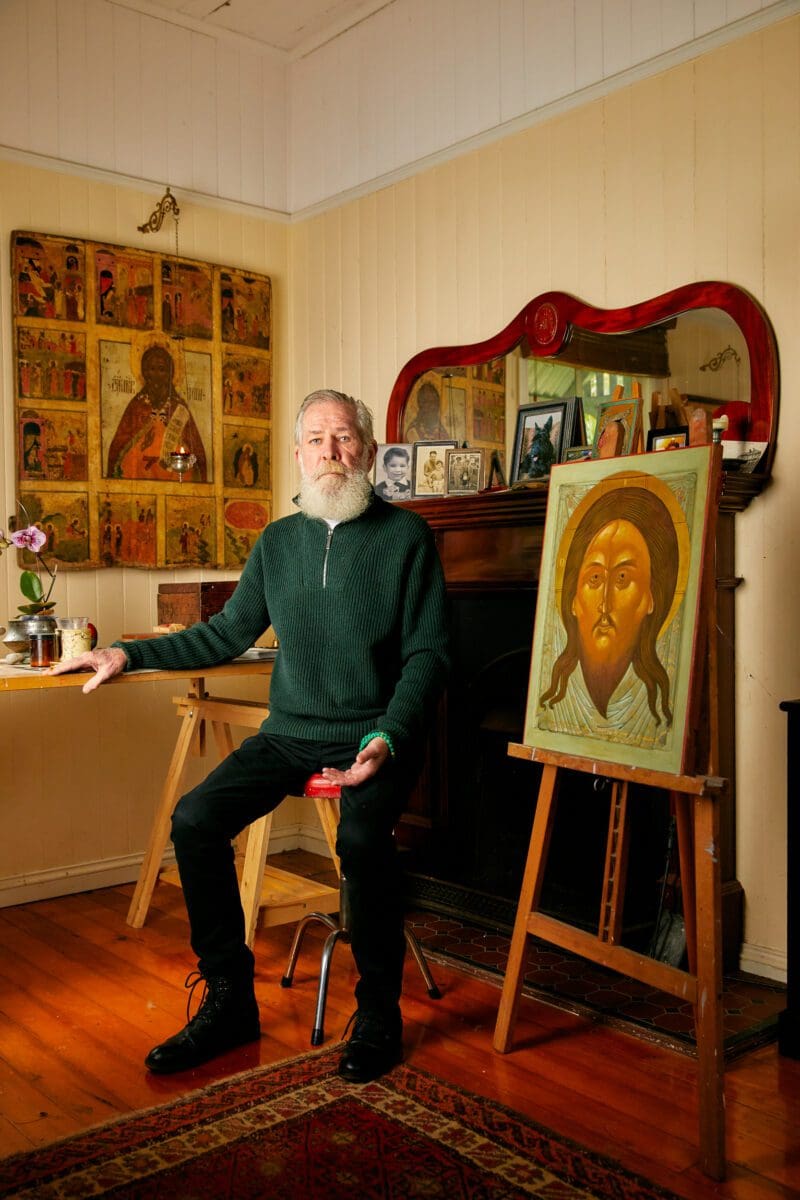

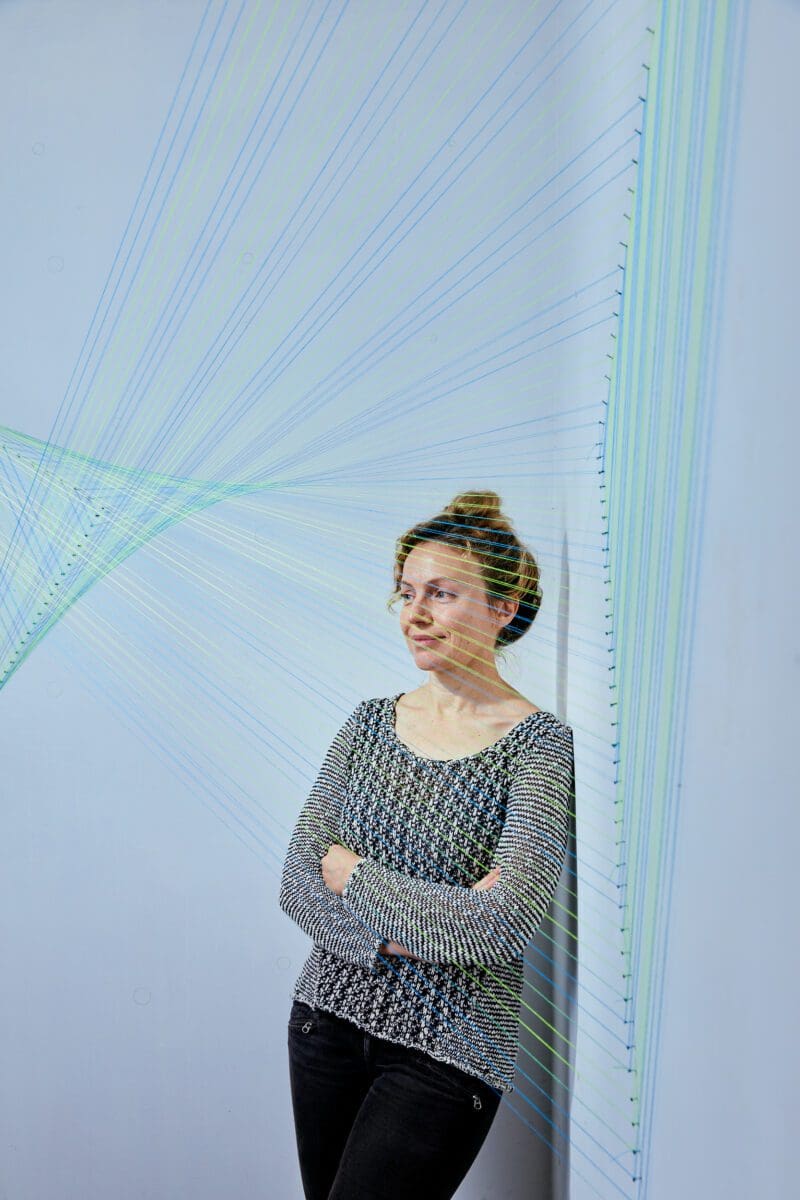

This is a triangulation of sorts: the works and objects are complementary responses to the interviews. The inclusion of recent works by each artist answers the visitor question, “What are they doing now?” And personal and studio materials selected by each artist suggest their working methods.

Fiona Foley and Anne Wallace, for instance, both elected to emphasise their connection to the State Library: Foley suggested books written by members of her Aboriginal family and her own recent books about the history of Aboriginal peoples in Queensland. And Wallace lent reference books that recalled her student visual research in the State Library: she loves the film noir-style covers of hardboiled detective thrillers by Margaret Millar and Ross Macdonald. Other artists contributed studio materials (Leonard Brown and Sandra Selig), or objects that had inspired them (Judith Wright, Luke Roberts); Eugene Carchesio contributed an exquisite group of experimental studies.

Since 2010 the State Library has been steadily amassing a group of filmed interviews with eminent artists, plus gallerists and, so far, one museum director, Doug Hall, long-time director of Queensland Art Gallery. These are all interviewees who live, work or have exhibited in Queensland. The first interview—Vernon Ah Kee in conversation with broadcaster Daniel Browning—was in December 2010. Subsequent interviews range from senior figures such as Richard Bell, Jennifer Herd, and William Robinson, to younger artists including Selig. Currently 34 interviews have been completed, others are in production, and the series is ongoing (and can be found online via the State Library, making it accessible for audiences Australia-wide, indeed anywhere).

It’s a project that records history in a diversity of ways (with the funding support of James C. Sourris AM, and his sister Marica Sourris). It’s a typical, if unusually well-funded, oral history project, and far more usual in libraries than art museums.

This has long been a distinguished field in Australia: in 1957 the pioneering Hazel de Berg commenced audio interviews with writers (and later more than 250 visual artists), now held at the National Library of Australia. And while many art museums— notably including the State Library’s sister institution Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) and international institutions such as the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, MoMA in New York, and the Tate in the United Kingdom— make excellent videos with and about artists and their work, these are not often complete life biographies. So not only in Australia, but internationally, this is an exceptional project.

What distinguishes the James C. Sourris AM filmed interviews is that they exist in three formats, driven by oral history methods: a short digital story, typically no longer than seven to eight minutes, with extensive visual material; a longer interview, around 30 minutes, described as ‘educational’, excellent for classroom use; and an oral history of around an hour, which preserves as much of the original filmed interview footage as possible. The importance of this historical resource cannot be overstated. Four interviewees have already died, including much-loved painter and poet Madonna Staunton, and the great gallerist Ray Hughes. These interviews are particularly poignant, showing the ability of film to capture how the artists lived and worked, how they saw themselves and, indeed, what sort of people they were.

Meet the artists gave me an unexpected opportunity: to work with familiar artists in a completely different register. Yes, this was artist and curator in dialogue, as always, but the purpose was not to amplify aesthetic effect but to bring together different forms of information, assembling different materials—films, art, studio tools, memorabilia, references—that together cross-pollinate the processes of memory. In a country with a propensity to forgetting, remembering artists in their own words, and seeing them in their homes and studios, is enormously valuable. As well as hugely enjoyable.

Meet the artists: From the James C. Sourris AM Collection of Artist Interviews

State Library of Queensland Gallery

Until 9 July