Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

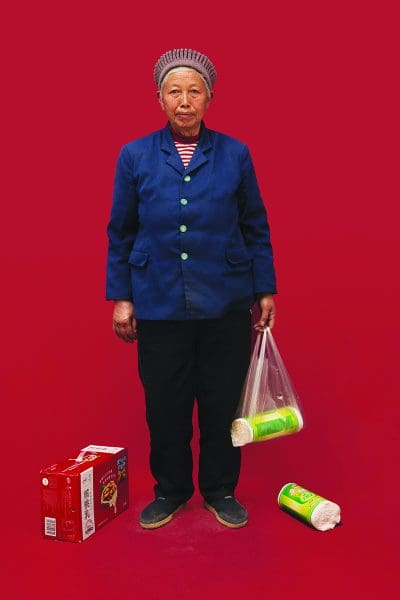

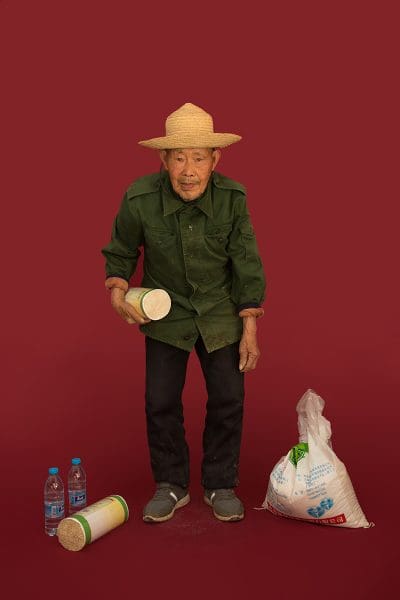

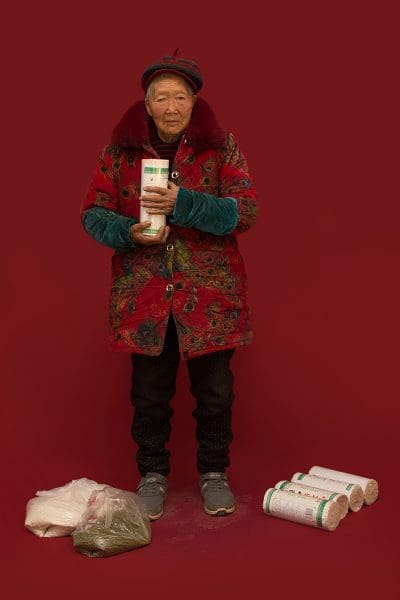

Tami Xiang, Lucky88, 2019, photography, archive printing paper, 80 x 56cm.

Tami Xiang, Lucky88, 2019, photography, archive printing paper, 80 x 56cm.

Tami Xiang, Lucky88, 2019, photography, archive printing paper, 80 x 56cm.

Tami Xiang, Lucky88, 2019, photography, archive printing paper, 80 x 56cm.

Tami Xiang, Lucky88, 2019, photography, archive printing paper, 80 x 56cm.

Tami Xiang, Lucky88, 2019, photography, archive printing paper, 80 x 56cm.

Tami Xiang, Lucky88, 2019, photography, archive printing paper, 80 x 56cm.

Tami Xiang’s Lucky 88 is a socially engaged photographic series involving elderly people from her rural hometown of Luotian in China’s Hubei province. Xiang sought out elderly residents on the aged pension, and gave them 88 RMB (around $18 Australian dollars) to buy whatever they wanted.

Her subjects stand against a red background holding what they’ve bought—mostly rice, noodles, soy sauce. There are a couple of things they buy that aren’t necessities—more than one person has bought a lollipop, one man got cigarettes. For the most part though, these are people from a generation that has lacked any sense of luxury.

For the most part they feel very lucky to receive a government pension; looking back on their own lives and history, they consider themselves fortunate. Hence the title Lucky 88: 8 is considered a lucky number in Chinese culture. When considering their circumstances compared to people living in cities though, Xiang sees their situation as a great injustice.

In Xiang’s view, this injustice comes through the Hukou system–a household registration system that acts like an internal passport. Families are designated a status as either an ‘agricultural’ (rural) or ‘non-agricultural’ (urban) household. Their access to government support, public services and education are determined by their Hukou status. While rural pensioners receive 88 RMB a month from the government, urban pensioners receive up to dozens of times more.

This rural-urban divide has been the foundation for some of Xiang’s other projects too; her Family Portrait series tackles the issues of China’s ‘left behind’ children. For millions of families, one or both parents need to move away for work, and there is a generation of millions of children who are being raised by their grandparents—with families only being reunited intermittently. A UNICEF report from 2018 found that there were 69 million children living in a rural area who’d been ‘left behind’.

Xiang’s father was a bricklayer who often worked away, and is one of the many millions of parents who move out of rural areas for work. For the most part, these ‘migrant workers’ are often those who find themselves at the bottom of the global supply chain working in factories, or they staff restaurants and shops for urban restaurants, or take jobs as domestic workers for the urban Chinese middle class.

In representing this, Xiang’s series consists of portraits of incomplete families. On either side of the works are images of grandchildren with grandparents, and of physically distant parents. Down the middle they’re separated by train tickets, which track the distance that parents need to cover to see their families.

Some of the children in the images see their parents once or twice a year, sometimes less. Because of the segregation between rural and urban areas, and the economic constraints and cost of living in the city—as well as unequal access to stable housing—it’s more practical for families to be split. This can go on for most of a child’s life.

The images are woven together with personal family photos from the people that Xiang worked with, using a weaving technique prevalent among rural farming families. It speaks to the depth of the bond that is being broken, and the ways of life that are being uprooted in the urbanisation of the country. It is also a way to make the works more ambiguous: when shown in their original form, the works came under the scrutiny of the government. A large group exhibition that they were included in, alongside other politically charged works from well-known dissident artists, was shut down. Posts about the works on WeChat were quickly removed.

Government censorship has led generations of artists to think deeply and creatively about how to speak out on these issues in an indirect and metaphorical way. The title Lucky 88 is thus meant to be indirect in identifying Xiang’s position on the unequal access to state support, but she hopes it speaks volumes and that it opens up discussions to international audiences.

This article was originally published in the March-April 2020 print edition of of Art Guide Australia.

Tami Xiang

Peasantography—Lucky 88

Bunbury Regional Art Gallery

3 April – 23 May 2021