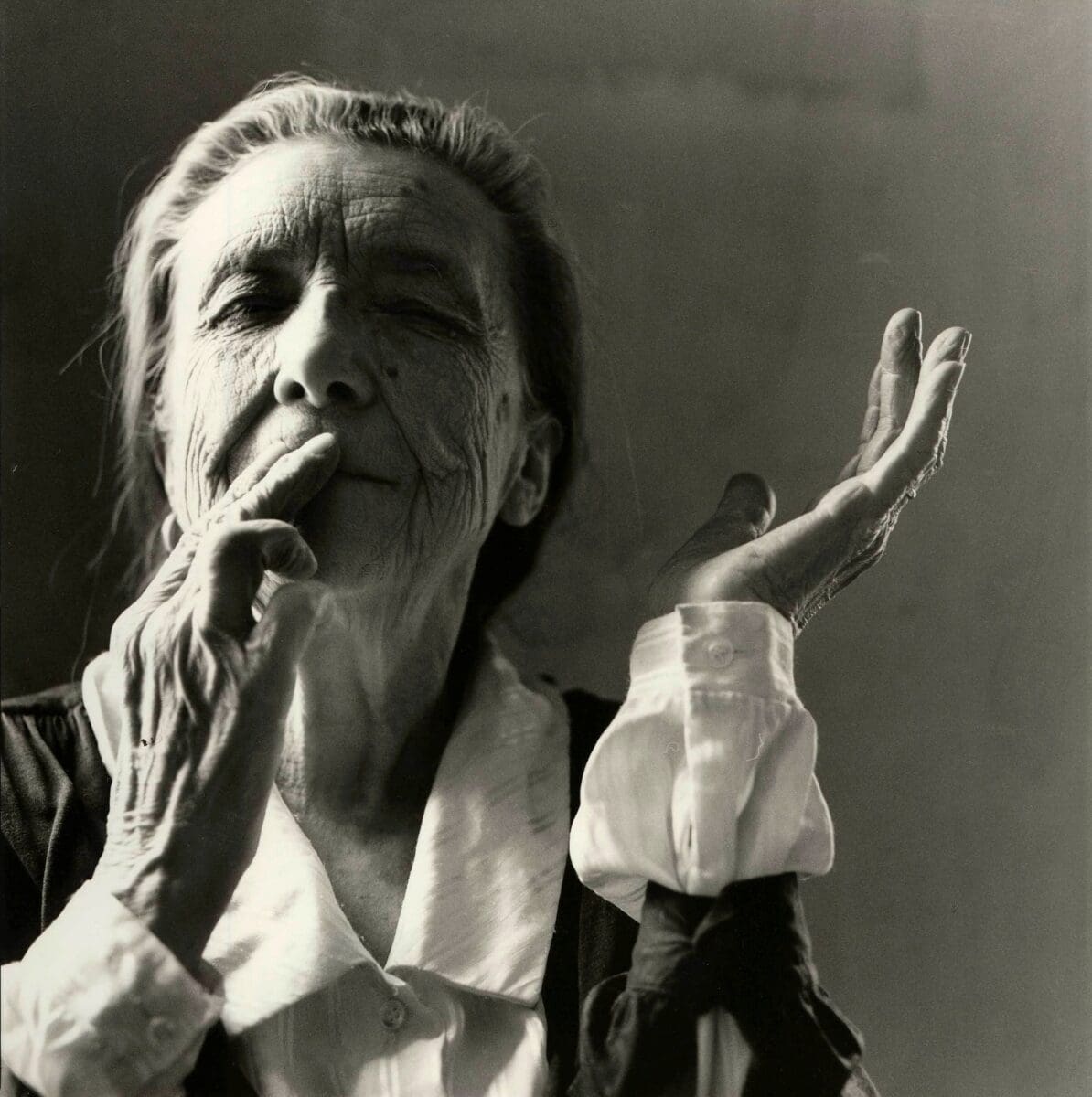

Louise Bourgeois is the kind of artist that gives one shivers. A giant of 20th century art, she’s most known for her textiles and large-scale sculptures (she was also a painter and printmaker), through which she fearlessly interrogated the extremes of intimacy and personhood, sexuality and mortality, the conscious and unconscious.

Born in Paris in 1911, Bourgeois later moved to New York in 1938, where she died in 2010, aged 98. She began to receive wide acclaim in her seventies, and it is said that she produced some of her greatest work in the last two decades of her life.

This summer the Art Gallery of New South Wales is showing the largest Bourgeois survey ever exhibited in Australia. We asked five Australian artists influenced by Bourgeois—Juz Kitson, Louise Weaver, Nadia Hernández, Natalya Hughes and Prudence Flint— to each write about one artwork in the exhibition.

Juz Kitson:

Mother. We all have one. Crouching Spider represents the sheer protective nature of the mother. Always there. Present. Watching.

I first encountered this work in 2016 at Dia Beacon in New York. It had a profound effect on my senses; the stillness of its scale, matte bronze finish against the backdrop of crumbling red brick, its vastness of form, cumbersome and strong yet elegant and graceful. The elongated legs as if captured in a moment of time. I watched children, unafraid, running around and climbing its legs. It felt safe.

And then, in an entirely different setting, I saw another spider at Art Basel 2022, blue chip art collectors frantically squabbling over the work and the clinking of champagne glasses as it was acquired for an exuberant amount. This opposite context was bewildering, though I realised Bourgeois had united us from all walks of life, collectively protected by her.

Recently I’ve started to explore ideas of connection to mother as I bear witness to the ill health of my own mother. Nothing prepares you for the loss of your mother. As a woman, a daughter and potential mother dedicated to my art, I wonder if this human desire to copulate and give birth arrives to some of us in a more transcendent way. To quite literally give birth to form. Form within ourselves.

Louise Weaver:

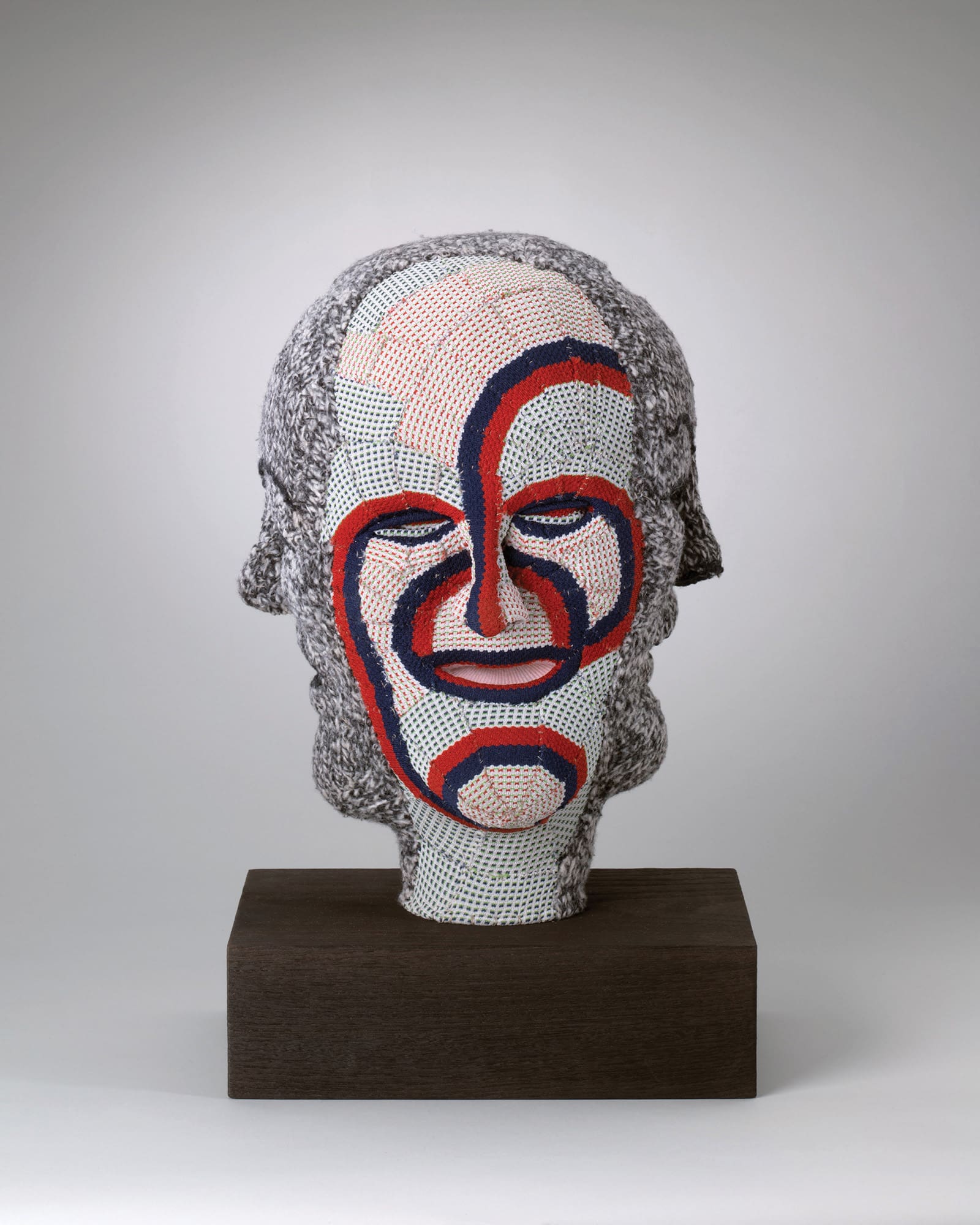

Bourgeois’s enigmatic sculpture Untitled, 2009, a head featuring four faces, draws us closer and beckons touch. I imagine my finger tracing the contours and shadow lands of its expanded terrain. Following red and blue pathways in a meandering pattern. Stitching, reparation, and quilt-like piece (peace) making. Uncanny, contradictory, woolly headedness.

As an artist passionately engaged with material processes and concepts myself, I have been fortunate to have experienced many of Bourgeois’s significant exhibitions firsthand. These include her 1993 Venice Biennale presentation and 1999 Serpentine Gallery exhibition, where several of her sculptures incorporating items from her extraordinary personal wardrobe and other ‘talismanic’ textiles were shown.

Until her death in 2010, Bourgeois continued this trajectory, creating both two-and three-dimensional works including a series of soft padded fabric heads. For Untitled Bourgeois repurposed grey marled knitted textiles and fabric, summoning a stippling pore-like pattern, to conjure the multiple aspects of this singular form. Relating in part to her earlier drawings of Janus, the ancient Roman god of beginnings, transitions, time, and endings, this work is less a conventional portrait, instead an evocation of diverse emotional and psychic states.

As Bourgeois said, “We have been given life and we are supposed to be thankful for it by leaving an account of it.”

Nadia Hernández:

Recently, I was introduced to a concept called the shock of shame. Described by a dear friend as the sensation generated upon encountering artworks which induce an emotional reaction. The shock of shame being the defining moment in which something you are yet to know is revealed, and a reaction is shaped by a shift in perspective.

I untangle this concept more as an impulse, which can have any emotion as its precursor. The shock of horror, euphoria, contempt, fear, disgust and aggression are all embodied in Bourgeois’s The Destruction of The Father—a work I felt drawn to for its ability to push emotional thresholds.

It is intimate and confronting. Bathed in red light, the multi-sensory dining room/bedroom contains an unrecognisably shaped, fragmented body. In this scene, Bourgeois conjures a dream in which the children turn on the father at the dinner table—and dismember him. In her exploration of power and paternal figures, Bourgeois truly pushes materiality by casting chunks of meat out of plaster and latex rubber.

I will crawl into any lair crafted by Bourgeois, in hope of liberation or resuscitation… maybe some of us need it right now? Perhaps then we can move beyond our apathy and reconnect with the depths of our emotion, taking account of the societal challenges we’re facing.

Prudence Flint:

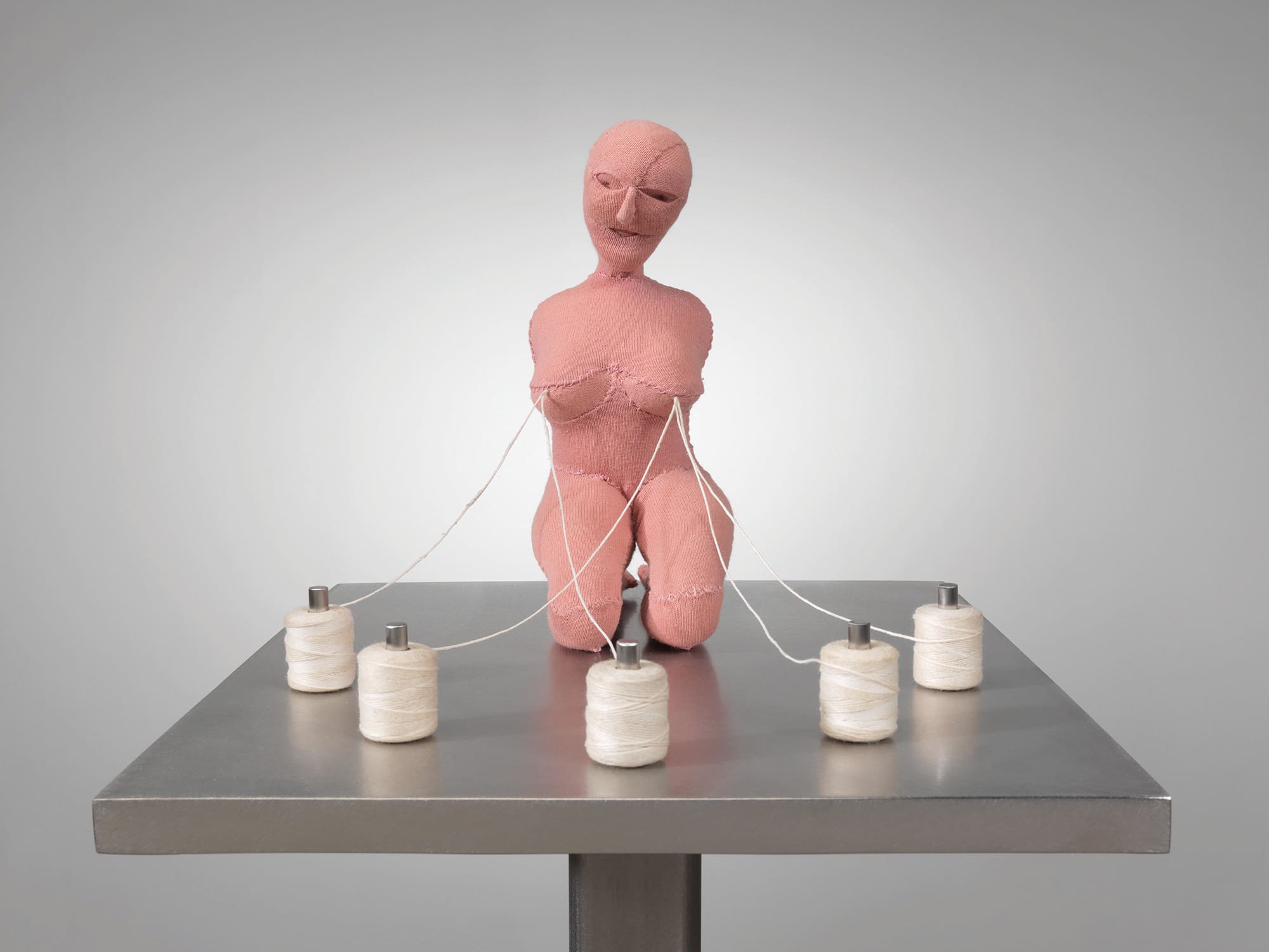

Armless in bandage pink with a face like a thief or a sex mask. Nothing good about the white spool strings that attach and threaten to pull from the nipples. The spools sit around her, timeless on steel, like a secret faceless family. The finely constructed legs, breasts, and torso, handstitched, form an unsettling second skin. There is recognition, familiarity, comfort, and the overriding threat of displeasure all at once: that is The Good Mother.

Bourgeois worked throughout her long life across many mediums. In her last two decades, she explored sewing-based works. She took her mother’s old clothes and her childhood dresses—white camisoles, underwear, nightgowns, with their smell, shape, colour, weight—and refigured them into works. These are intimate in their looking backwards as repair and reparation, and a claim for forgiveness. Bourgeois stands out as inventive and agile in her exploration of the darkness of female subjectivity. Her interest in psychoanalysis allowed her to overcome repression to make works that are embodied and perverse, taking on strenuously the situation of being female and all its powerful particularity.

Natalya Hughes:

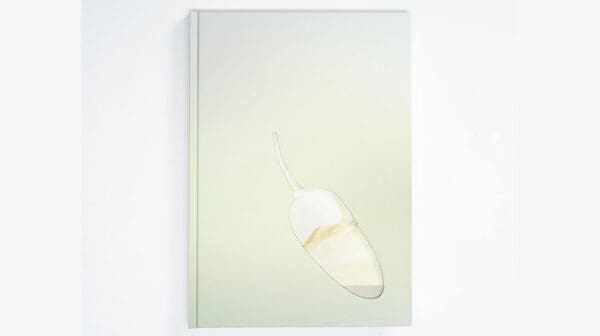

It is difficult to describe Janus Fleuri without resorting to a list of opposing terms: the work is figurative but abstract; wound-like and open at its centre, but self-contained by its nubbed, closed and vaguely phallic limbs. The heft of its bronze constitution is counterposed by its delicate suspension like an object of lesser weight. Its surface textures are organic, molten, lumped, but then suddenly smooth, glossy, impossibly polished, and perceptively cold to the touch.

Based on such binaries it’s been discussed as both masculine and feminine in character, taking its title from Janus, the two-faced god who looks to the past as well as the future. But Janus is also the god of gates, passageways and beginnings. And whether Bourgeois’s object is seen to hold such binary oppositions, or actively undermine them, might depend upon the (historical) position of the person writing about them.

In our own time it is now commonplace in art writing to speak of the non-binary. We throw this term to embrace the critique it belies; that binaries are their own fiction. That Bourgeois’s object of the late 1960s accommodates this sensibility is impressive. Janus Fleuri sends its message; an embrace of the in-between, from its time and place to our own.

Louise Bourgeois: Has the Day Invaded the Night or Has the Night Invaded the Day?

Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney NSW)

25 November—28 April 2024

This article was originally published in the November/December 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.