Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

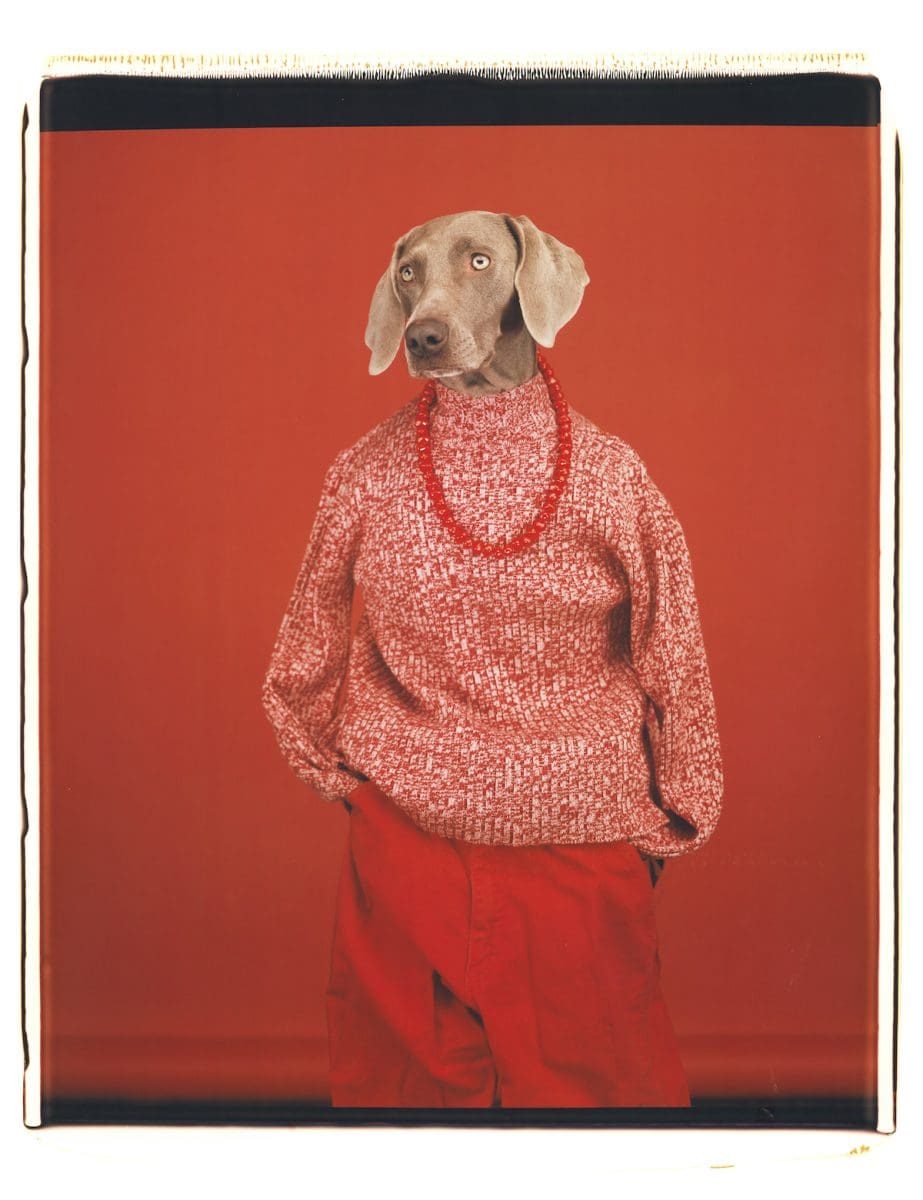

I am staring at a sitter, who is staring back at me. The longer I look at this photographic portrait, the greater the sense that I am not only the observer but am also the observed. He is framed by a dark, sombre background and is garbed in robes that designate him as a member of an episcopal order. There is a wisdom in the sitter’s eyes that almost draws a confession of sin out of you; a soft understanding and a concentrated concern. Yet, looking at Ecclesiastical, 2000, I’m caught between an urge to genuflect beside him and the impulse to stroke his fur.

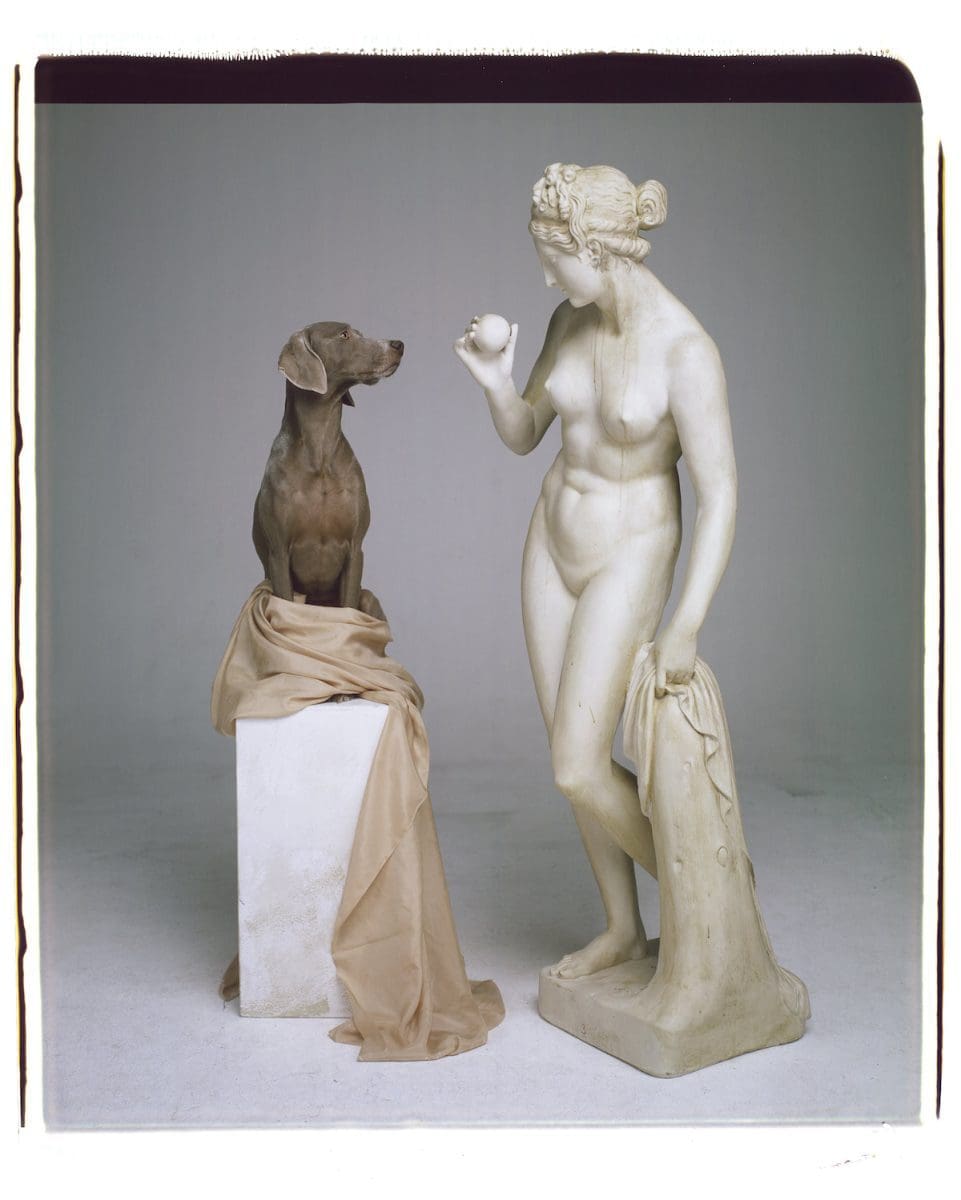

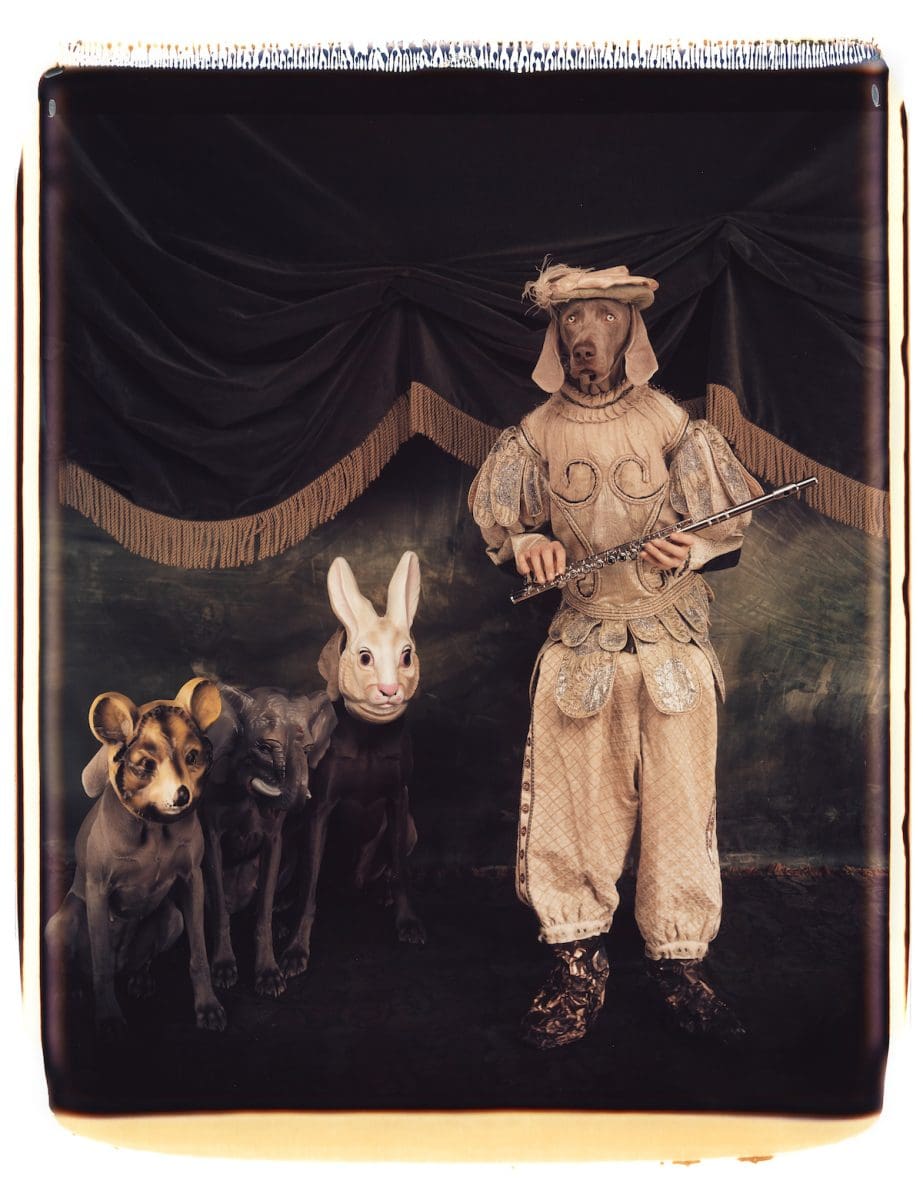

Being Human, the artist’s exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), tracks three decades of relationships between the artist and his sitters. Wegman’s portrait photography invites gallery-goers into an intimate setting and its success rests on the finely balanced dissonance between a familiar subject and a foreign framing of it. His works are neither traditional portraits nor endearing depictions of pets; instead they are uncanny refutations of both of these comfortable genres. If one were to write down a list describing the formal aspects of Wegman’s work – a dog, a vestment, and a clerical hat – you would likely tear up the paper and move onto the next idea. Wegman was not sold on it himself, as he initially resisted clothing his subjects. “I really avoided that like it was the plague because it’s such a weird thing to do and its cute, or trite, or wrong,” he explains to me, from his studio in New York. “But when I did it at first, it just looked eerie and almost like I was making creatures out of mythology.” Because no matter how it looks on paper, somehow it works on the wall.

Wegman’s portraits are more than just uncanny curios. He treats each of his subjects with the kind of respect that is typically afforded to a human sitter, and the kind of candour that is only afforded to man’s best friend. “I have never been comfortable photographing people,” Wegman confides. “But there is really no embarrassment on my part staring at a dog and asking it to do things.” He has worked with 10 dogs since 1970, but, hearing him describe them, I’m struck by the inherent individualism that he locates in each of his sitters. “I have two dogs right now and one of them is really serious and you empathise with her because she gives you a lot of psychology and the other one is just magnificent and handsome and is no trouble,” he says. Indeed, the dogs are not merely passive receptacles for the artist’s vision, they clearly occupy a role that goes beyond this – they are collaborators. “If you’re working they want to be part of it,” he observes.

In many ways, this close collaboration has led to Wegman becoming synonymous with his iconic muses. “If I really want someone to go ‘Oh you’re William Wegman,’ I’d show them a picture of one of my dogs,” he concedes. “It’s the first thing that people think about.” The success that has been born from this association is self-evident, so I ask the artist about the other side of the coin: his frustrations. He pauses thinking about my question, and I’m left to think about his thinking. And I can’t help but think that there is something very telling in the artist’s brief silence. One gets the sense that this is why his portraits are successful: his ability to sit with ideas and find nuance before answering the question that each artwork inevitably poses. “Not anymore, but certainly over the years I have had those feelings,” he says. “When I started to paint again in the mid 1980s it was really great to have a whole category of work where I wasn’t going to be asked to go on a talk show, but I also missed photographing the dogs – so now I do both without guilt.”

While Wegman’s exhibition captures a cross-section of his oeuvre, it is still overwhelmingly dominated by his older polaroid photography. “This show is really the result of me going back 30 or 40 years with this camera, and finding that there was lots to show that I had stored away in boxes,” he says. As he speaks, I find myself imagining the artist looking through his attic, rummaging through boxes for work that will eventually make its way onto the walls of one of Australia’s leading arts institutions. I’m not sure why, but there is something irresistible in that. Yet I am not alone in valuing the romantic ideal of the neglected box. “When I moved from LA to New York, I left and I forgot about a box,” Wegman recalls. “John Baldessari took over my studio and years later he mailed it to me and I started to sweat like crazy, because it was so significant to me to see this treasure that I thought was all gone.” At the NGV, we finally get to share in this treasure.

Being Human

William Wegman

NGV International

7 December – 17 March 2019

Closed 25 December