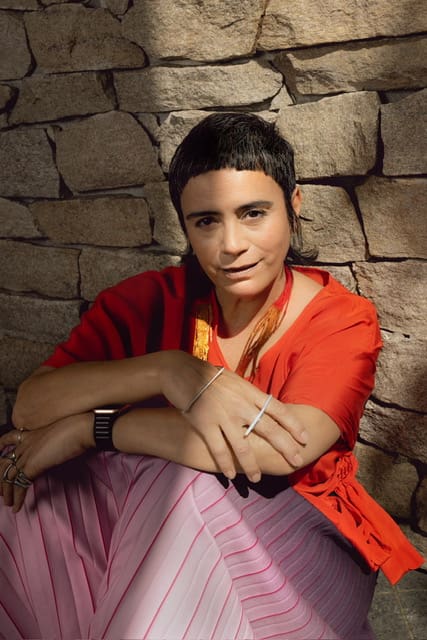

Auckland-born and raised artist Lisa Reihana is ever the optimist, creating two new works signifying social cohesion to hang outside two Australian arts venues just as dark divisions seek to undermine the value of migration and Indigenous sovereignty.

“All humans want to belong to some community, whatever you call it—clan, mob, whatever,” says the 60-year-old, seated in the regional gallery Ngununggula, a Gundungurra language name meaning belonging, in Bowral in the New South Wales Southern Highlands.

“I just think the world is in such a pickle now; I find it scary. As an artist, we are like magicians—you have an idea, and you manifest it into a space where other people can see what you’ve been thinking about.

“So, it’s a good idea to talk about cohesion when clearly there isn’t [as much]. My politic is quite soft—through storytelling, I try to demonstrate caring for others. Maybe you change one person’s mind, two people’s minds, but it’s not going to happen in a hurry, clearly.”

Across the entrance outside, Reihana’s specially commissioned work Belong shimmers in the sunlight, its zigzag tinsel pattern recalling the cloaked arms of Māori warriors performing a haka, welcoming visitors here to Voyager, her second survey (the first was at Sydney’s Campbelltown Arts Centre, in early 2018).

For Reihana personally, art became a way to reconnect with Māori culture. Her father George, birth name Huri Waka, of the Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hine and Ngāi Tu clans, left his tribal homelands in the 1950s in search of city work, meeting the artist’s mother, Lesley, who had come to New Zealand from London at age eight when her family searched for a better post-war life.

“Becoming an artist, I could see that was a place where I could learn more about myself,” Reihana muses.

Inside Ngununggula, four rooms display five video works Reihana has created over the past five years, featuring costumed actors dancing their creation stories or challenging brutal colonial histories, wed to haunting soundscapes by her life partner, the percussionist and sound engineer James Pinker.

Meanwhile, 100 kilometres north-east of Bowral, Reihana has unveiled another welcoming work, this one for the exterior of the Sydney Contemporary art fair at Carriageworks in inner-city Eveleigh, a sculptural piece that glitters with thousands of discs, referencing a waharoa—a Māori gateway—and a pare, for which te reo (Māori language) dictionaries provide many definitions but in this context means the carved slab over the door of a house.

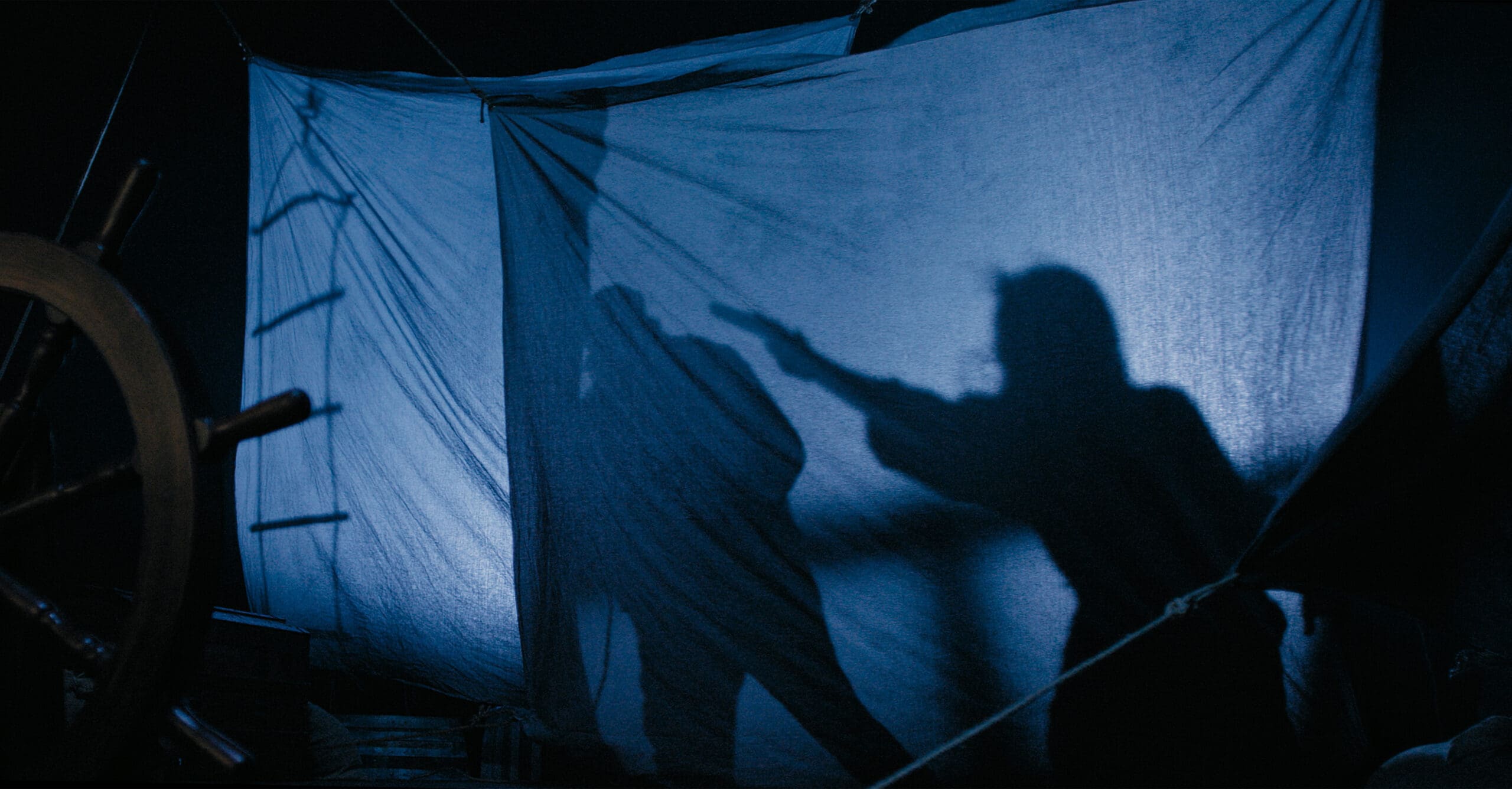

However, it is the video works for which Reihana is best known. Her rolling installation In Pursuit of Venus [Infected] became her career calling card in the international art world, representing New Zealand at the 2017 Venice Biennale, utilising an array of costumed actors to satirise the Pacific adventures of Captain James Cook, as fawningly presented in the 1804-5 panoramic wallpaper Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique by the painter Jean-Gabriel Charvet.

In Reihana’s take, which continues to be exhibited around the world, successive versions of one scene see a man and then a woman pull Cook’s breeches down, because to some Pacific cultures, whose tribal dress purposely showed genitals, Cook’s gender would have been unclear. “I wanted to queer it up,” Reihana told me in a 2018 interview.

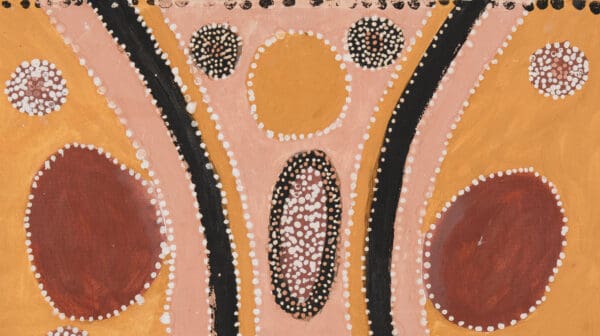

The newer works at Ngununggula display a mesmerising, sophisticated beauty, particularly Māramatanga, a 2024 video installation in the first room, in a smaller iteration than the huge original work commissioned by Auckland University. In it, six dancers perform as ancestral, creation and spirit figures inspired by carved figures in the university’s marae or meeting house, against a backdrop that alternates between psychedelic patterns and naturalistic locations of rainforest, mangroves and ocean.

Reihana is concerned our attention has been diverted from the state of the environment: having first come to Australia in 1988, taking up a residency at the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney, she has credited this country with helping raise her cultural awareness and crystallising some of her thematic concerns, so she was aghast when encountering the anti-immigration demonstration in the city here in late August.

“It made me feel sad. How do we end up here, when we know so much? We really should be in a different place right now. Maybe there’s going to be a pendulum shift—guaranteed, it always happens. The annoying thing is we’ve been distracted from ecological issues, because no one can pull it together.”

In the second room, Reihana’s monumental video work GOLD_LEAD_WOOD_COAL, also from 2024, utilises actors to tell a moving story of migration across three large walls—in this case, Chinese miners, some of whom had faced racism in the 1850s Australian gold rush, taking up their diasporic story in New Zealand from the 1860s onward, including the SS Ventnor cargo ship sinking off the country’s Hokianga coast in 1902.

The ship had been repatriating the remains of hundreds of Chinese gold miners to Hong Kong and Guangzhou. Movingly, and reflecting historical fact, a Māori woman and then a man sing over the bones of the miners in Reihana’s video. In bygone times, bones would be exhumed after a year and cleaned, placed in boxes and put into caves, Reihana explains.

For all the specifically Māori stories in this survey in the Southern Highlands, Reihana emphasises that Voyager, as the title of her show, is about being “in other places, and with other cultures”. She hopes these cultures can play off each other, demonstrating harmonious possibilities.

Lisa Reihana: Voyager

Ngununggula

Bowral / Bowrel NSW

Until 9 November 2025

Sydney Contemporary

Carriageworks

Sydney / Warrane

11—14 September 2025