Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

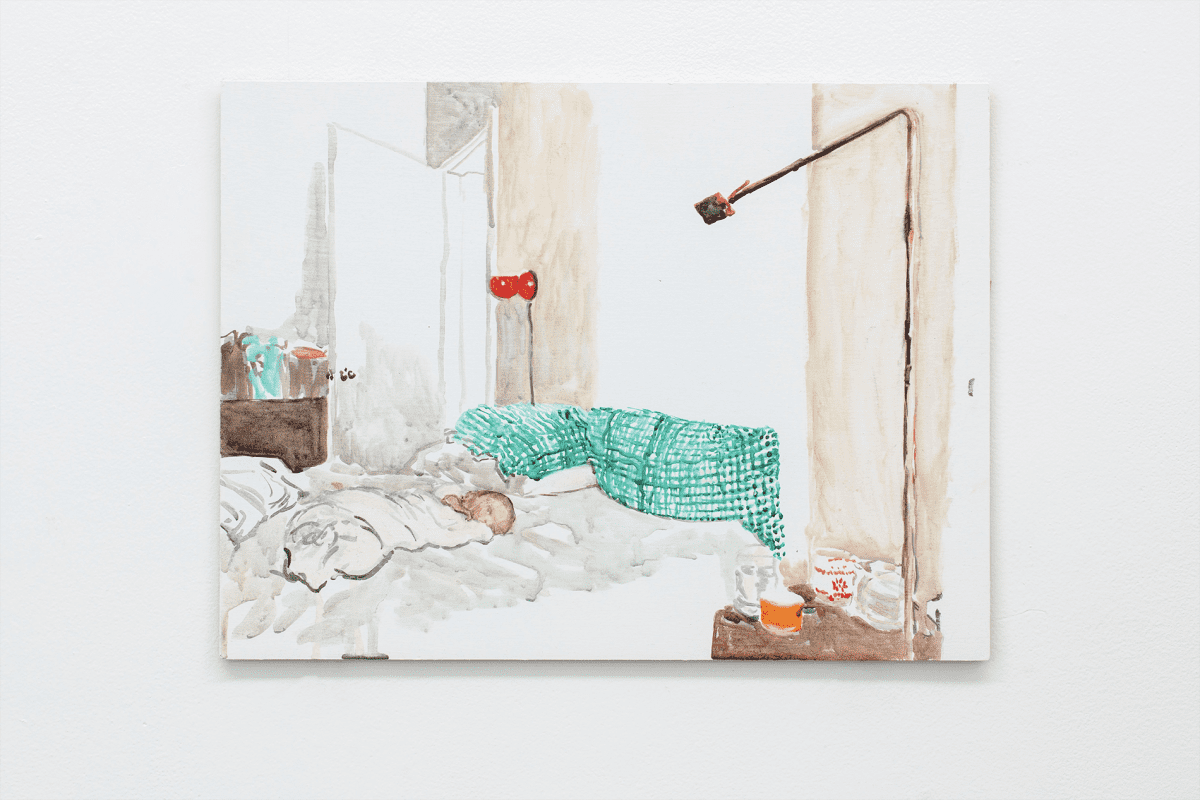

Nicola Smith, Late morning, at home, 2022, water colour on board, 30 x 40cm.

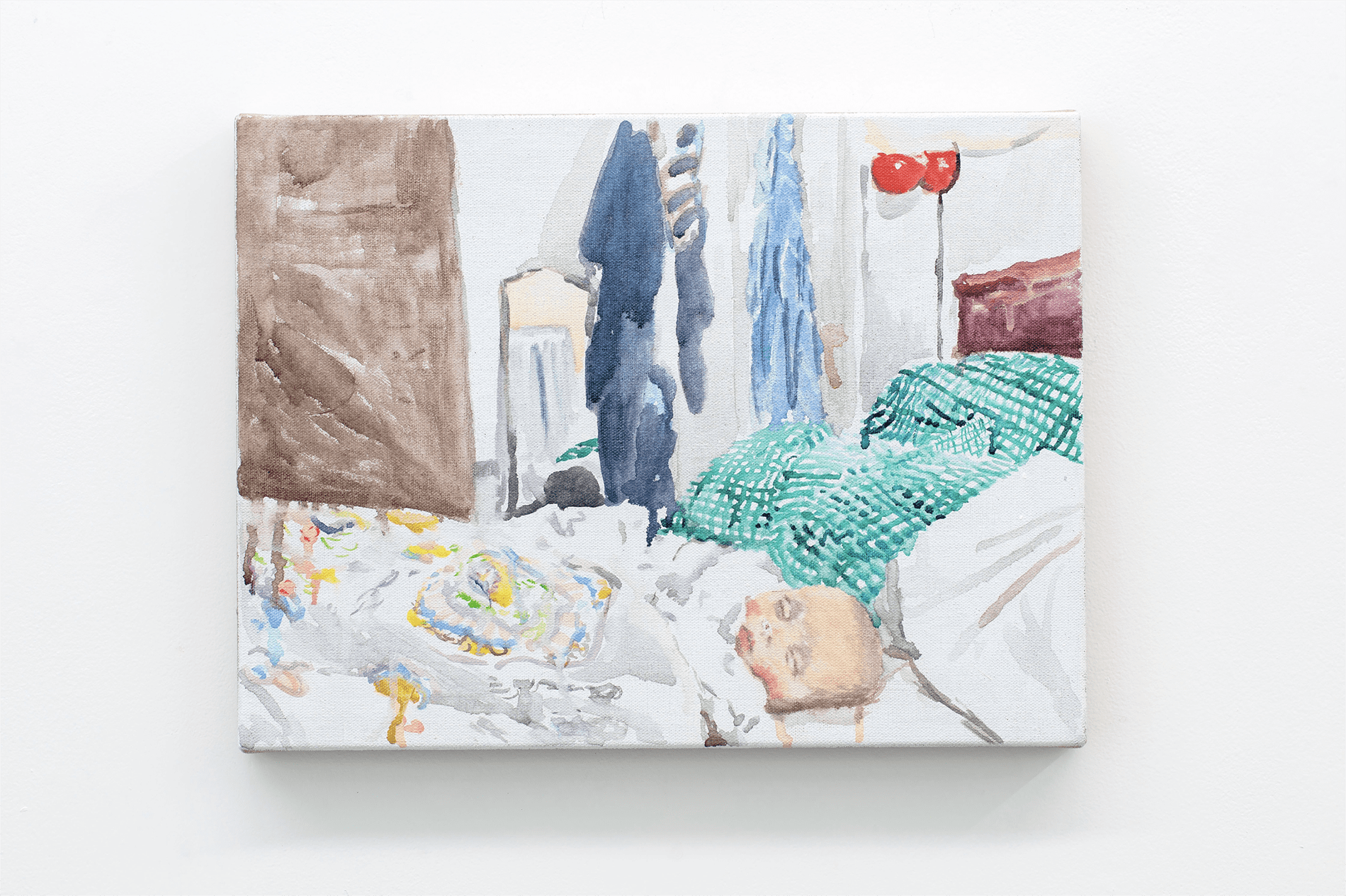

Nicola Smith, Afternoon, on the train home, 2022, water colour on Belgian linen, 30.5 x 41cm.

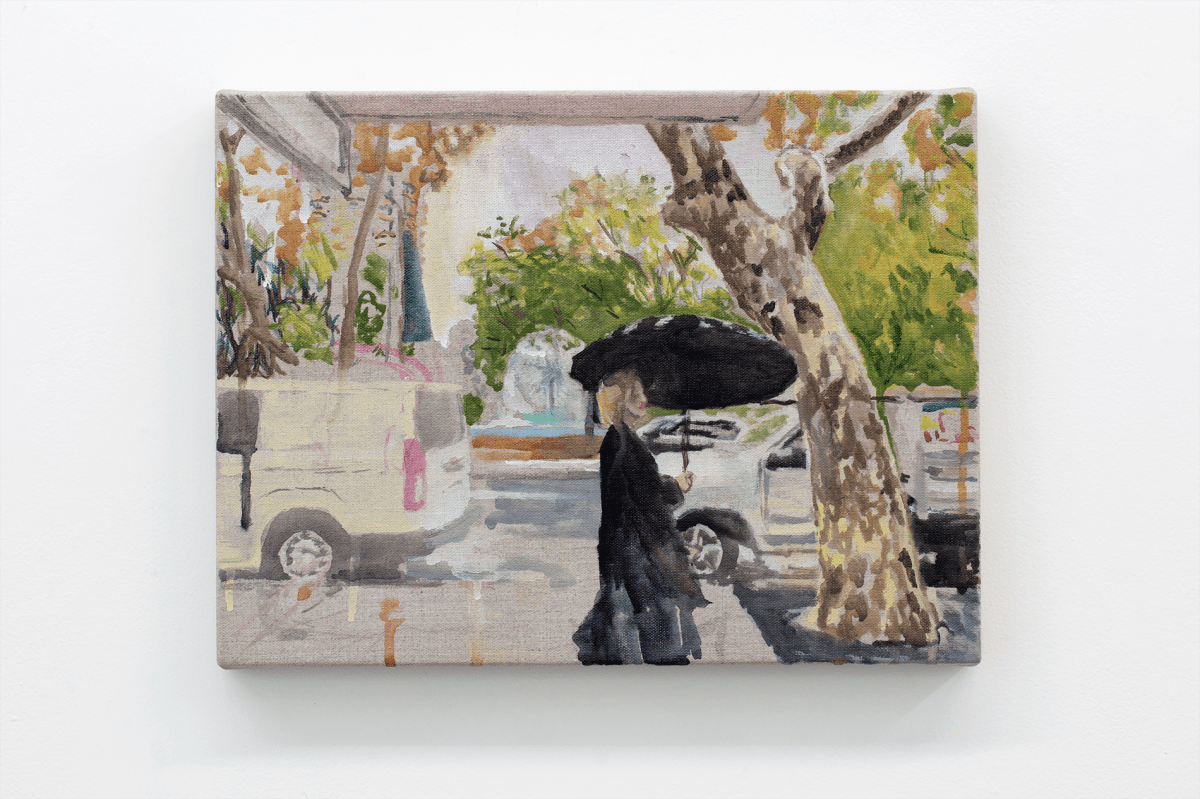

Nicola Smith, Lunchtime, in the rain, 2022, water colour on Belgian linen, 30.5 x 41cm.

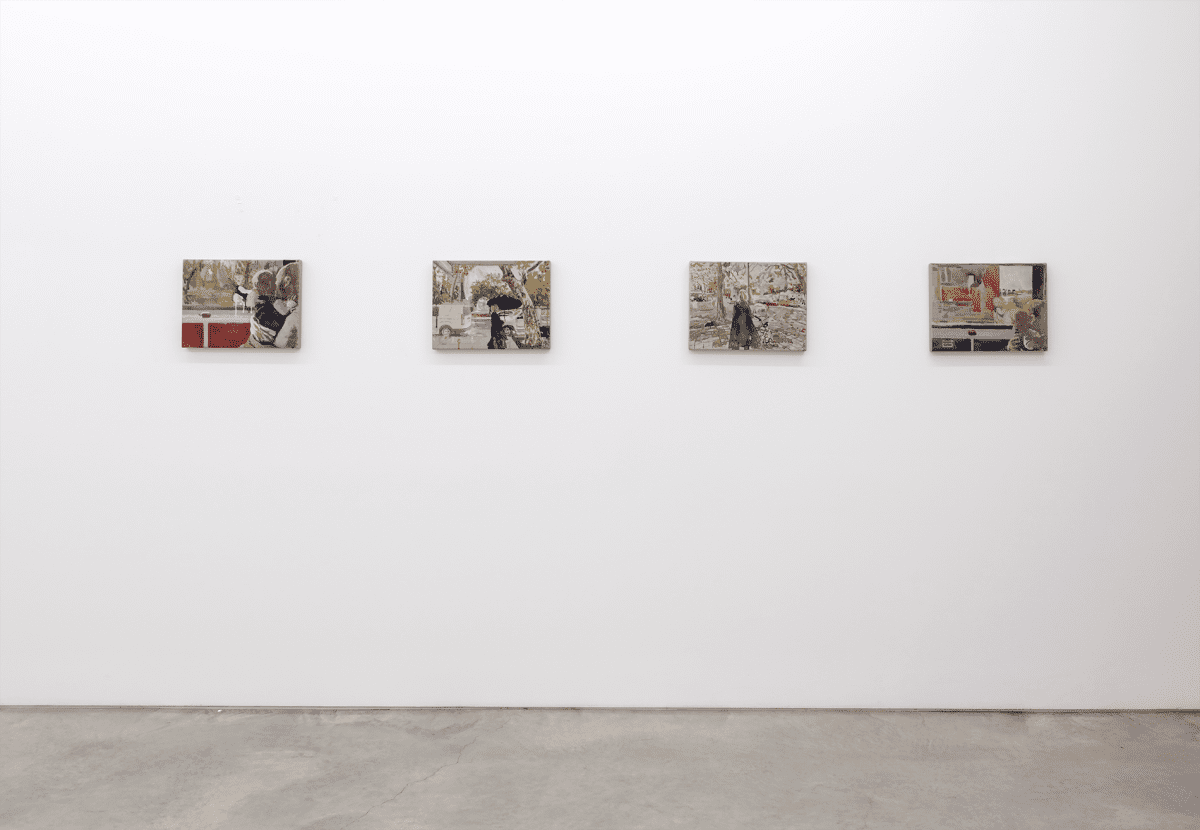

Nicola Smith, Antonio, 2022, installation view.

Nicola Smith makes paintings about moments. Her practice has, up to this point, revolved around film stills, derived from movies by directors like Chantal Akerman, Buster Keaton and Benoît Pilon, among others. Smith often produces multiple paintings of scenes that were shot only a few seconds apart from each other, suggesting an interest not in appropriation or repetition, but in capturing how no two moments, however close together, can ever be exactly the same.

By re-interpreting a film’s colour scheme and selectively painting each mise-en-scène intuitively, the Sydney-based artist brings compositional considerations to the fore. As thoughtful iterations of specific filmic moments, Smith’s works hint at how it is actually very difficult to explain why one painting may resonate more than another very similar one—a phenomenon of taste that owes as much to chance as anything else.

For Smith’s latest solo exhibition at Sarah Cottier Gallery, her sixth at the Sydney venue, change is in the air. Antonio is titled after her young son, born in January this year, right around the time that Covid-19 hit an intense peak.

Film has taken a backseat to family in these latest paintings, but Smith continues to use recurring perspectives, this time supporting studies of overlooked moments of domesticity. Of the iterative aspects of her practice, Smith states: “I’ve always loved looking at European Impressionist paintings in which the artist returns to the same landscape, looking out the window onto the same boulevard at different times of the year, different times of the day.”

For Antonio, the artist’s Potts Point apartment is what Mont Sainte-Victoire was to Cézanne; or, more aptly, what breastfeeding was to Mary Cassatt. The new works, all of which are watercolours (perfect for busy schedules), return repeatedly to scenes that are redolent of the first few months of new parenthood, when lounge rooms, bedrooms and kitchens are peacefully haphazard—evidence of little sleep, new love, obliging house guests and unacquainted routines.

“The new works are painted fast,” says Smith. “Beds feature extensively in Akerman’s films—characters lying down, waiting, sleeping in hotel rooms and at home—and they are often in my works from her films. They also feature in the new works, with figures that are lying down, sleeping, and resting.”

Born in Sydney in 1981, Smith is the younger sister of Gemma Smith, an abstract painter, also based in Sydney, whose treatment of colour and gesture, although very different, conveys a similar sense of sophistication complicated by searchfulness. After attending the National Art School in the 2000s, Smith had a five-year spell in Hobart, studying honours at the University of Tasmania, working part-time at the Museum of Old and New Art and undertaking a 12-month studio residency at Contemporary Art Tasmania.

The move to Tasmania gave Smith time to find and refine her oeuvre—to articulate how the compositional decisions she makes in the moment of painting respond to the comparative decisions made by the actors, stage designers and directors whose imagery she pinpoints. “I see the moving image as a painterly medium, inevitably impressionistic, a play of flickering light and shadows,” says Smith. “It’s of little importance if the viewer is familiar with the film or with the filmmaker, although I do adore the films from which I paint. The painting is all its own, but it is interesting what details come into focus when honing in on a particular moment, one film still within the 24 that make up a second of footage.”

In her more cinephilic works, which Smith still produces, and has done throughout the pandemic (in collaborative exhibitions with the video artist Elise Harmsen—also an Akerman fan), a palpable sense of ennui exudes from often ‘European-looking’ subjects, portrayed in beds, baths, and smoking and drinking at tables. Endowed with Criterion chic, the paintings are also about the legacies of such postures—the transference of old-school cinematic nonchalance into vaguely digital dispositions.

By contrast, a lot of ‘doing nothing’ in Smith’s new paintings are simply part of the everyday fabric of familial life. What is remarkable about them is how realism itself appears nostalgic. It’s as if Smith is deep in these moments of coping with newborn life but from some perspective in the future, performing an Impressionistic ‘push-pull’ between veracity and transience, the concrete and the abstract.

Given the sketchiness of our futures under lockdown, such an immediate yet far-reaching gaze now seems philosophically heavy.

While signalling a change of emphasis for Smith, Antonio isn’t without precedent. Staged at Sarah Cottier Gallery in 2019, New Hampshire 2006 was, at the time, both unexpected and emphatic. It consisted of muted, unfussy landscape paintings that Smith made 13 years earlier when she was an artist-in-residence in the United States, in forms and tones evocative of the Australian modernist Clarice Beckett and the reclusive American painter Albert York—both artists who were at odds with their times. Like that show, Smith is again casting off expectations that she be a ‘second-degree’ cultural commentator, championing, instead, the vagaries of first-hand observation.

Attracted by gestures of disaffection, Smith is, like Akerman, equally motivated by self-discovery. Without a care in the world for delineating between modern, postmodern and contemporary art, she perfectly fits the role of the sketch artist; out for the search more than the find.

Antonio

Nicola Smith

Sarah Cottier Gallery

(Sydney NSW)

9 July—6 August

This article was originally published in the July/August 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.