Six years ago, acclaimed Gomeroi poet Alison Whittaker wrote in The Guardian that “we’re in the midst of a renaissance in First Nations literature… So why do I feel this restlessness?” The restlessness she describes lingers, underscored by a literary industry that thirsts for Aboriginal writers but doesn’t always know how to hold these words with care. Award-winning Wiradjuri poet and academic Jeanine Leane encapsulated the quandary in 2023, describing in The Sydney Review of Books how, “In the main settlers are coming to our works with a toolkit, or a suitcase of cultural values, practices, and words packed for a different cultural sphere that needs to be unpacked.”

Leane’s incisive views left me curious about how we unpack Western values and whether approaching Aboriginal poetics is something that could be done beyond the book and in entirely different mediums. One of the most arresting poetic experiences I’d recently felt was through the work of Badimia Yamatji and Yued Noongar artist Amanda Bell. Her installation Ngobooloonginy (Bleeding) (2025), featured at Fremantle Art Centre’s Exhibition It’s Always Been Always, speaks back to coloniality through text in a gallery hallway. Handwritten in red paint across the white wall, she states: “I’ve eaten your violence, cooked with it”—a phrase that hits you with the type of power that risks feeling pacified on the printed page.

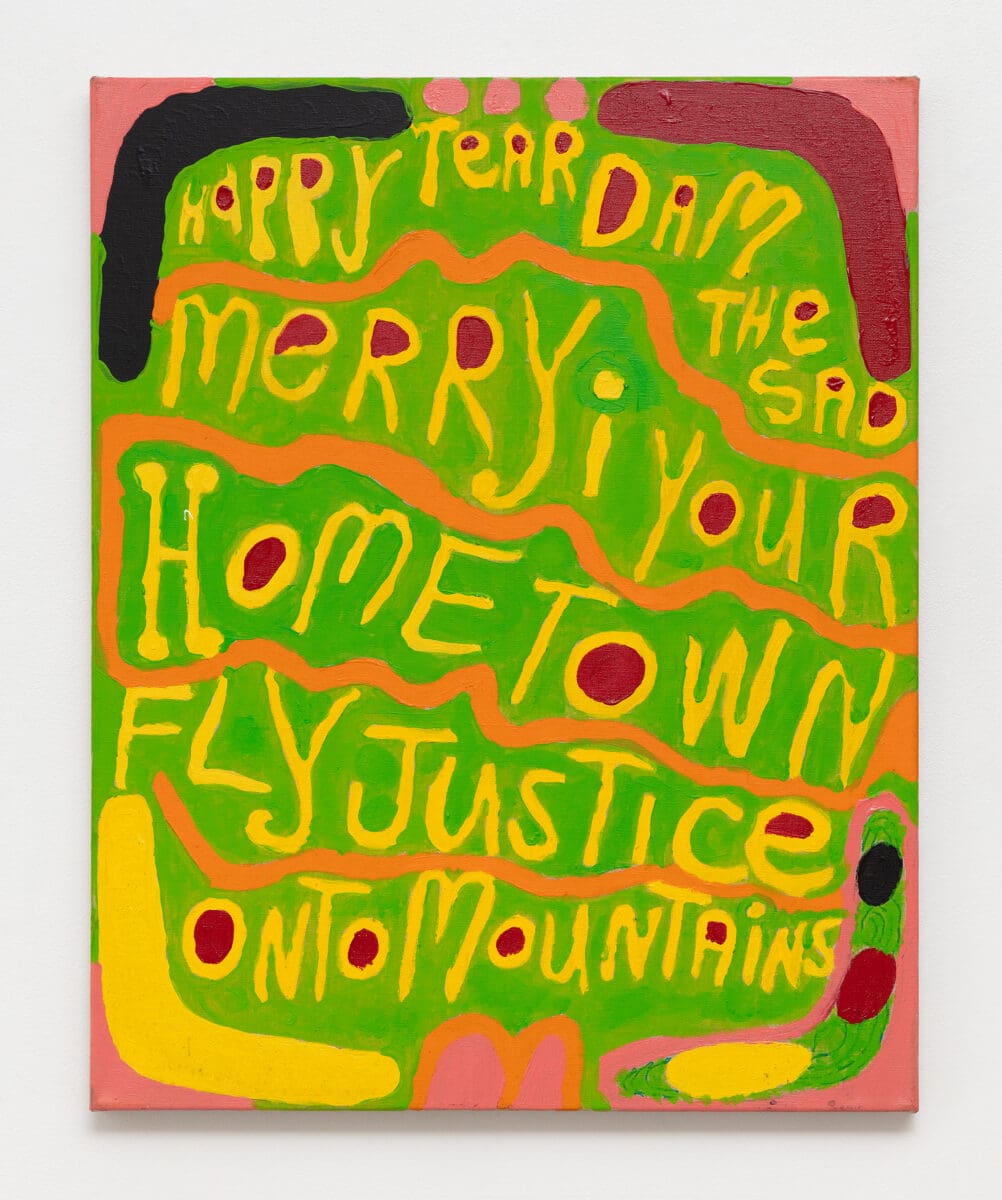

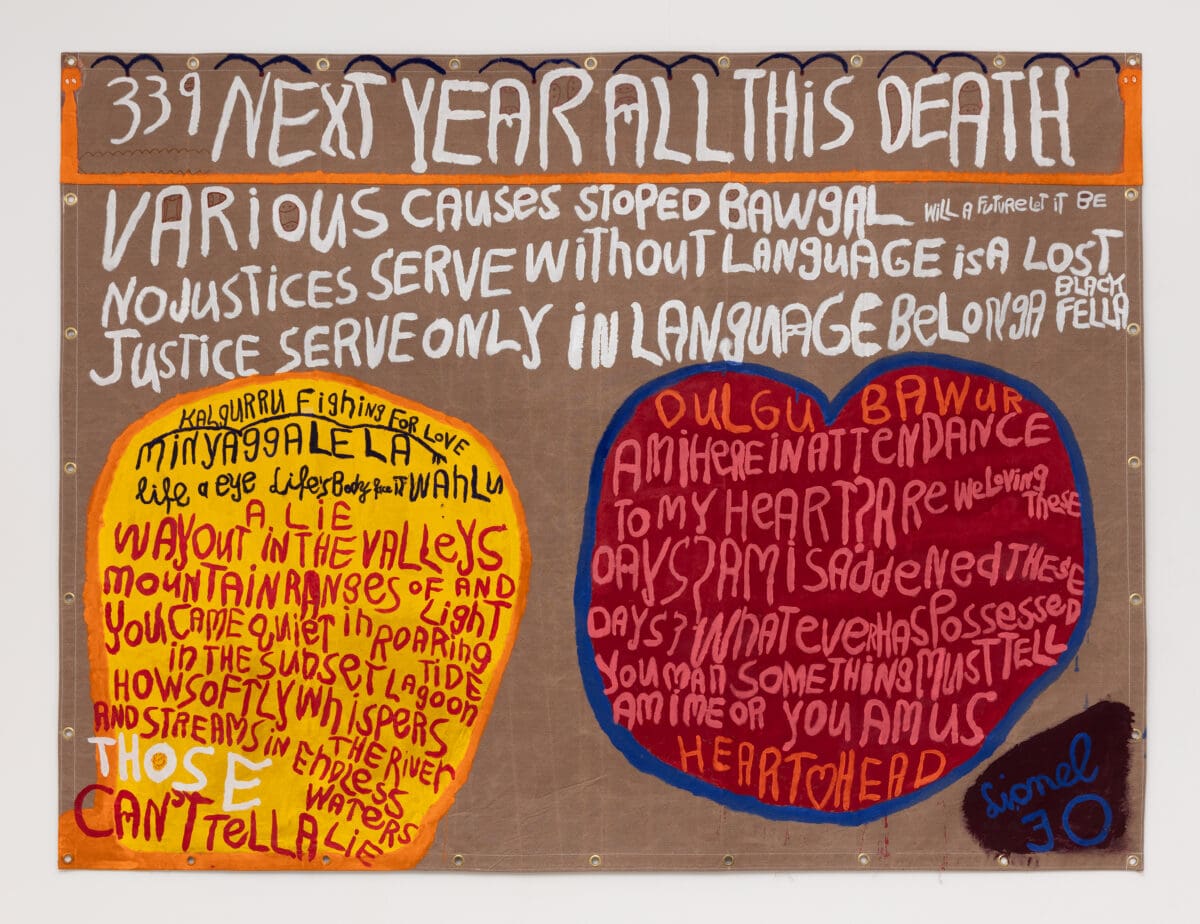

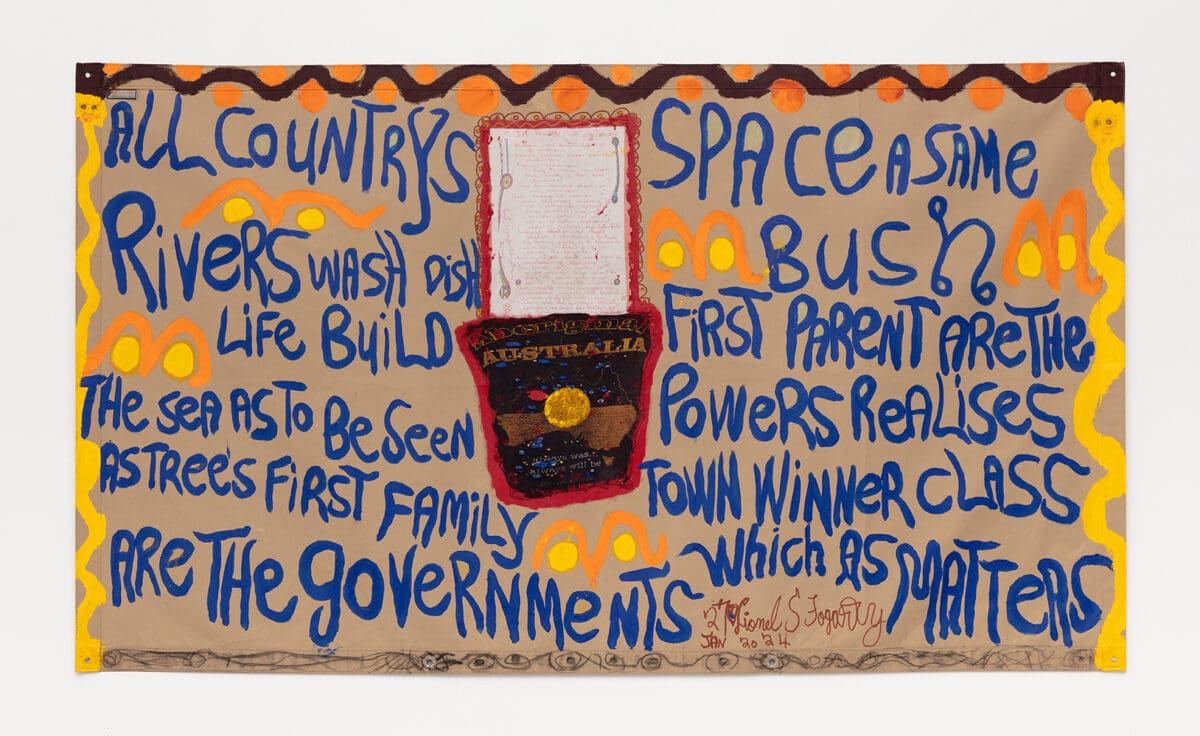

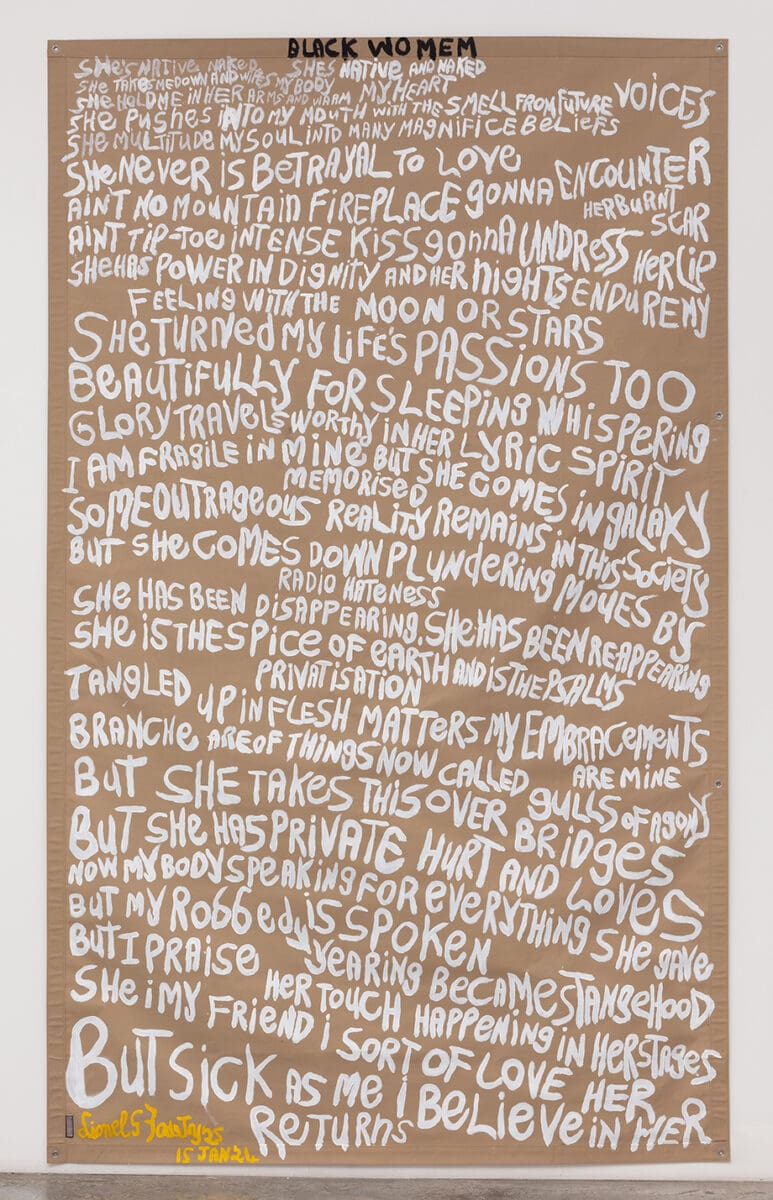

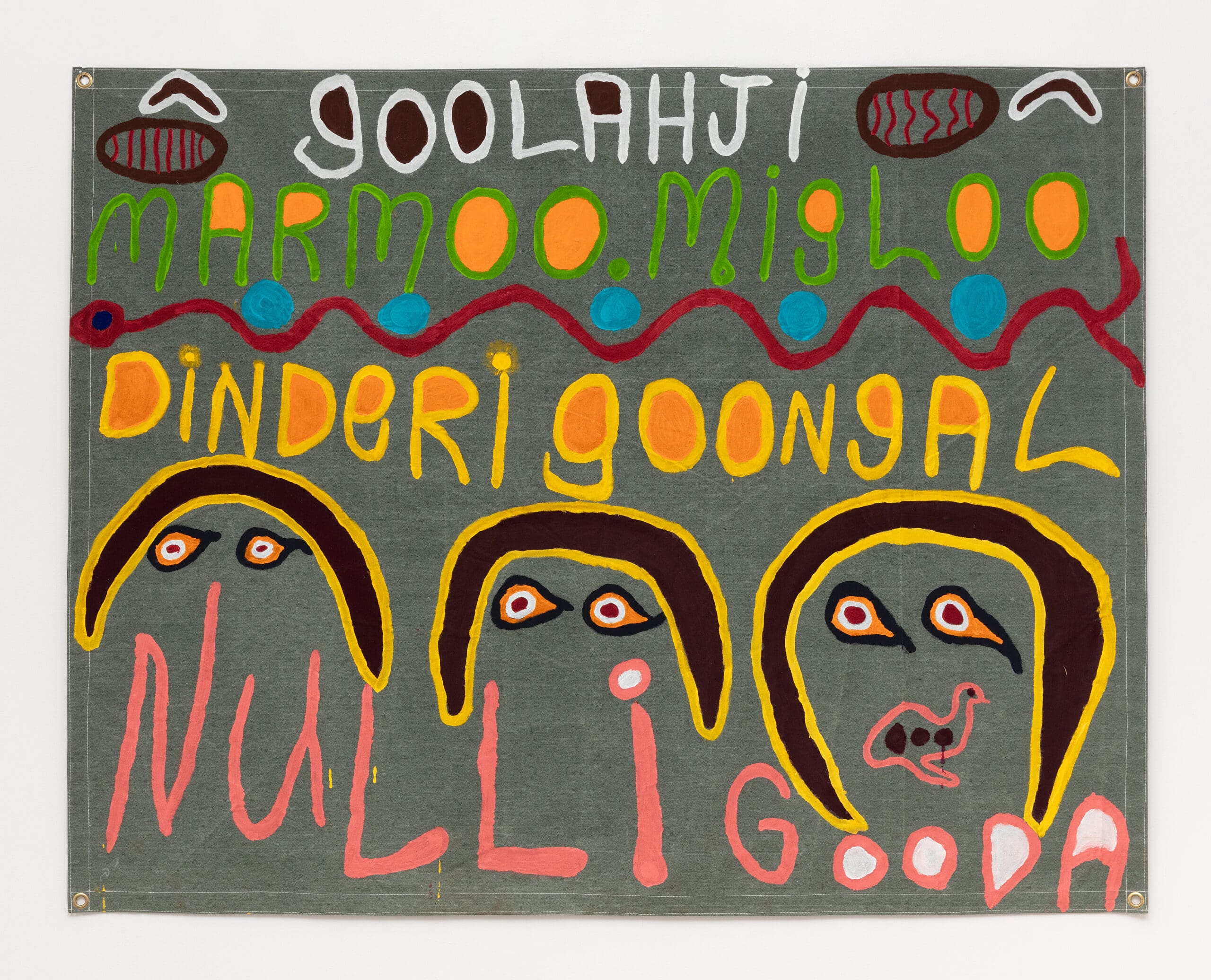

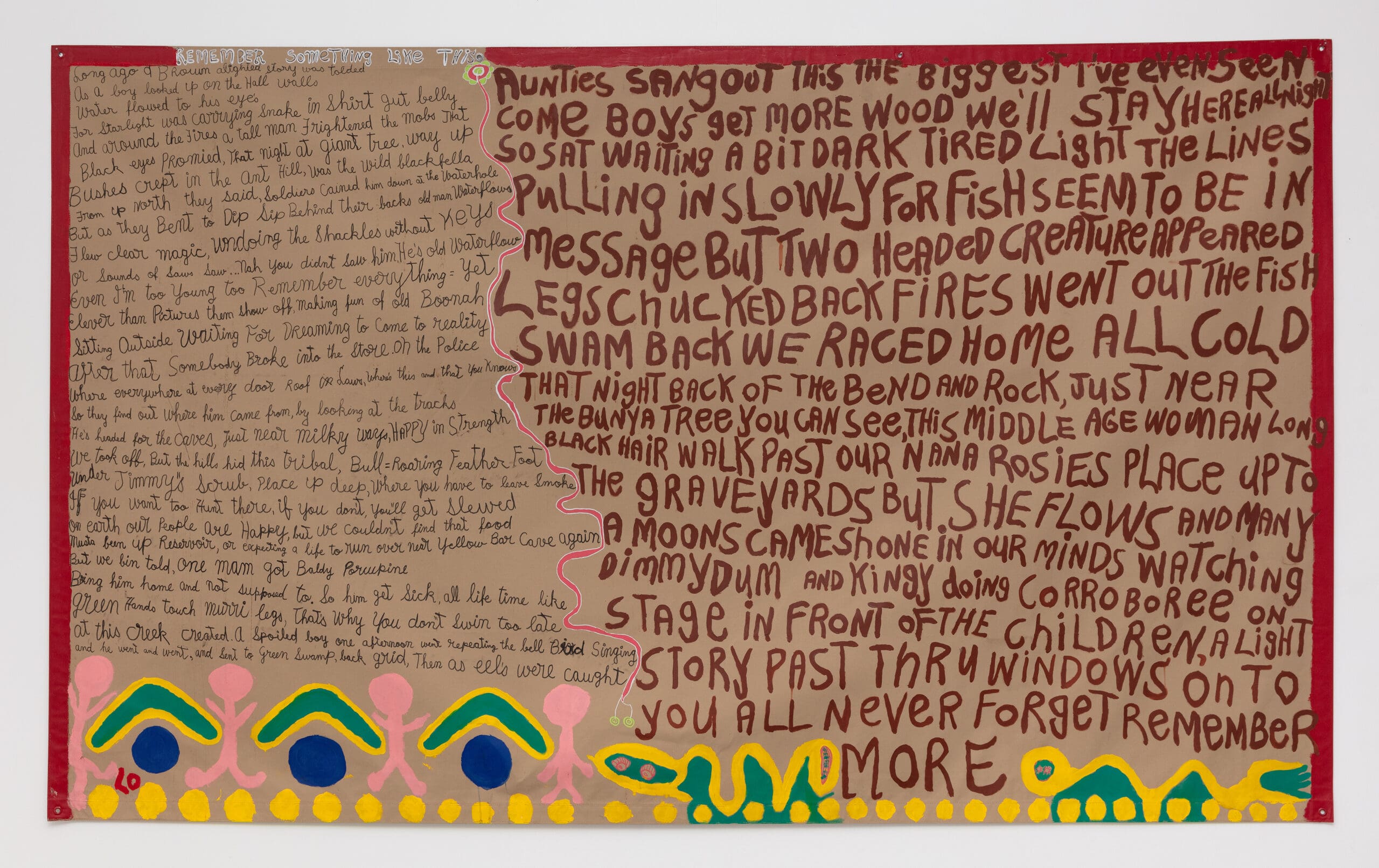

This approach—or toolkit—fervently unfolds in the paintings of poet and artist Lionel Fogarty, where dynamic words spill across the canvas and suggest a new way of reading, writing and approaching poetry. While Lionel, a Yugambeh man born on Wakka Wakka land in South East Queensland, is an awardwinning poet, having received the Judith Wright Calanthe Award at the 2023 Queensland Literary Awards for Harvest Lingo, there’s a potency to his paintings that elevate his poetry in ways the page doesn’t always hold. A solo exhibition at Darren Knight Gallery harnesses this power with a series of recent paintings that explode the poetic form. The aesthetic value is striking: large canvases showcasing vibrant text sit alongside drawings utilising bold colours, pulling the viewer in. But taking time to read the text leaves me wondering why poetry isn’t expressed and shared in paintings and other visual forms more regularly.

Each painting carries the urgency of Lionel’s activism in ways that feel more equipped than printed poetry. Works like 339 Next Year All This Death (2023) could easily slip into rhetoric if viewed on the printed page but instead feel like a call to act. And while gallery spaces are highly regulated, tainted by the same colonial toolkits that Leane is wary of within literature, it is still often easier to access art in institutions than poetry in books (limited by the cost of purchase or even the educational prejudices that dictate what is and isn’t literary).

Speaking to Lionel, activism has always been a critical driving force shaping his life and creative practice. And while he was illiterate growing up in the Cherbourg Aboriginal Reserve mission, Lionel understood the power of words. He moved to Brisbane in his early teens and became involved with organisations such as the Aboriginal Legal Service, the Black Resource Centre, the Black Community School and Murrie Coo-ee.

At 15, Lionel was arrested and charged with conspiracy against the state because of his political organising, public speaking and advocacy work. This experience fuelled his lifelong dedication to exposing deaths in custody, addressing land rights and recognition—urgent issues underpinned by racism. Lionel’s activism coincided with a desire to write and encourage others in his community to share their stories, which led to the Black Liberation paper. This resource ensured that his and other Aboriginal people’s stories were recorded and collected for those who couldn’t write themselves. But he quickly learnt to write, and by 22 had published his first poetry collection titled Kargun, establishing a practice that would result in 12 more books. And while his affinity with words has been prolific, Lionel describes an inclination to paint from the beginning: “I also knew that there was painting inside of me even though I wasn’t doing it, but I would think about painting after writing,” he explains. Realising that he was technically adept at painting he also knew he wanted to develop his own style, but it wasn’t until iconic artists Richard Bell and Gordon Hookey urged him to start exhibiting his work that Lionel understood the force and influence of painting poetry.

He experienced its effect on audiences in his 2024 exhibition Moiyum wungumbil mugerra bullonga at The Condensery, Queensland, describing how “when you get a book out it’s just black and white words on paper, but it was different in the gallery—even really young children were staring, looking and really enjoying it.” For Lionel, painting is a vehicle to engage with young people, forging intergenerational legacies that are crucial. He explains: “I want to do something that will be in the future and attract young people, I don’t want to be a book on a shelf that doesn’t move.” Reading his poetry as paintings demands attention, conveying stories in motion.

As he continues in this trajectory having just finished 11 new paintings, many utilising poems from Harvest Lingo, he will attract next generations and is unlikely to stagnate like words in a book.

Lionel Fogarty: Burraloupoo

Darren Knight Gallery

(Sydney/Gadigal Country NSW)

27 September—18 October

This article was originally published in the September/October 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.