In Lindy Lee’s recent Instagram reel she stands outside the Australian Capital Territory border, donning a bright pink cap emblazoned with “heavy haulage”, giving airtime to her newest heroes: truckies. We’re introduced to Nick, Liam and Ray. Everyone is so chuffed. It’s the most wholesome—without being maudlin—artist content you’ll find, especially when Nick says, “Alright, it’s been an absolute magical time being on this journey with Lindy Lee.”

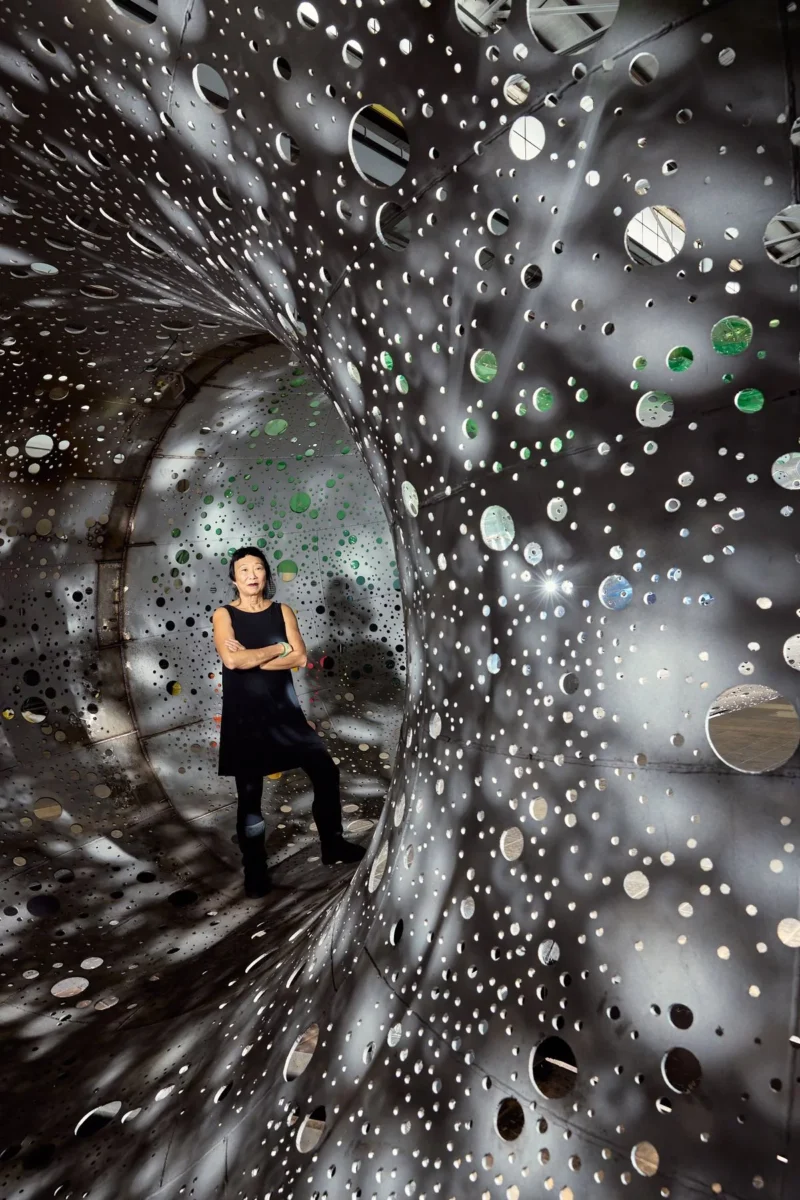

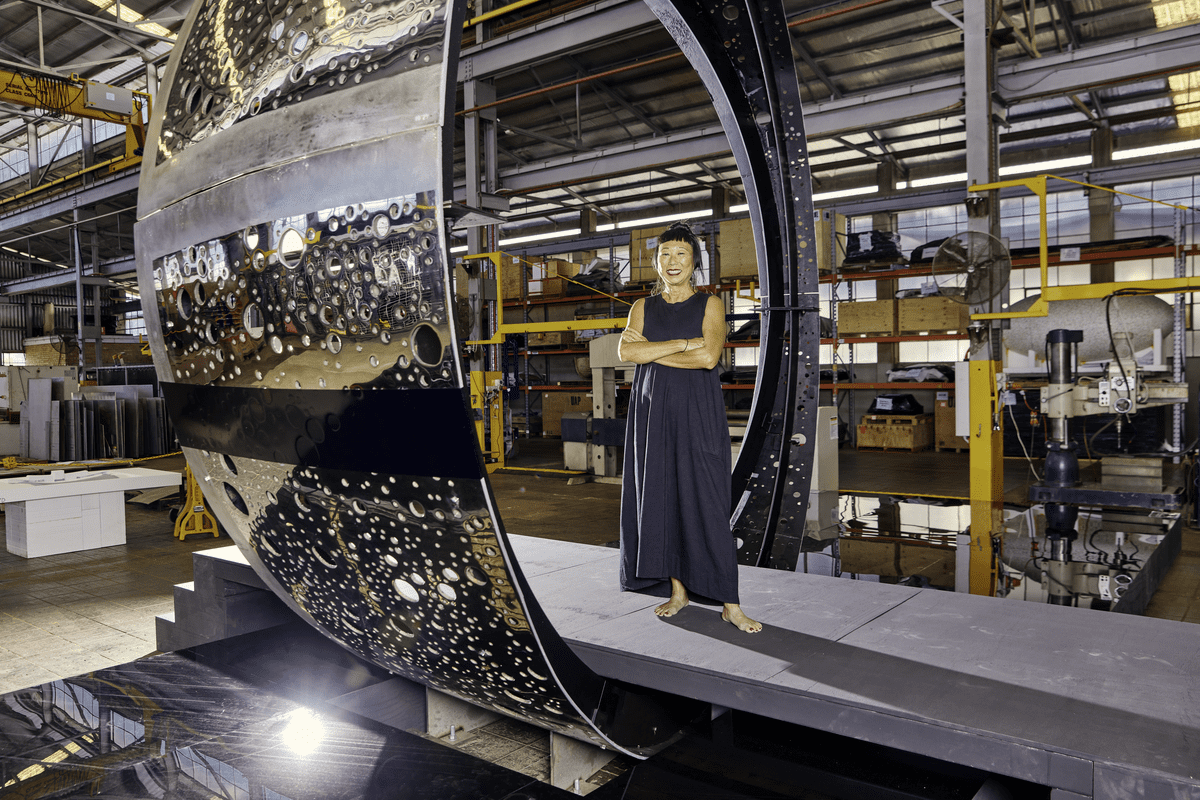

The group is transporting Lee’s career-defining artwork Ouroboros from Brisbane to Canberra, delivering the spiral-shaped, 13-tonne, reflective structure to its new home outside the National Gallery of Australia (NGA). Travelling across three states in over-sized vehicles with police escorts, often through the quiet of night, from the aerial images Ouroboros looks like a spaceship, a giant horn, a curious tunnel. Look closer and it’s a mammoth, refined steel structure, replete with the small perforations that Lee has been burning into different materials for years. Ouroboros is based on the ancient story of a snake swallowing its own tail, which, as Lee says in an NGA video, is “the symbol of eternal return, of cycles of birth and death, and renewal”. During the day its polished surface will reflect the world; at night it will be lit internally, returning light to the same world.

Commissioned by the NGA and costing $14 million, it’s the single biggest investment the gallery has given a work—and there’s almost no-one better to hold that achievement than Lee. Four years ago director Nick Mitzevich told Lee to be as ambitious as she wanted, so she decided that “I wanted to make a work that evoked infinity, and in that infinity a certain kind of absolute inconclusiveness.” It’s a representation of her Chinese ancestry through her Taoism and Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism practice where “everything is part of everything else”. It’s the space where being and cosmos meet. Now on a grand scale, where one can finally walk inside Lee’s work, it feels like the inevitable, destined culmination of 50 years of creating.

A few months ago on a Saturday afternoon, I ran an online workshop as part of NGA’s National Young Writers Program where I interviewed Lee with a small group of young arts writers from around the country. Lee talked about everything from belonging to broken hearts, to stating that the through line of her practice is, “What the hell—I’m going to swear—what the fuck is it that exists?” I’d watch small, enraptured faces across Zoom rectangles as Lee would say things like, “The only thing that life requires of you is that you have to be true to whatever you are . . . You have to be you. You have to step up, thoroughly, and be you. That’s the only job in town.” And it felt real. Potentially possible. Not like a parent replying to teenage woes with, “Just be yourself.”

Lee is ready for any conversation. She’ll drop lines about the nature of the cosmos before undercutting sentimentality with a joke, self-deprecation, a knowing smile. She knows she’s talking about things that are so fundamental yet also require so much of oneself. Her wisdom on life and art—which is always comedic, piercing yet calm, even a little punk—is as affecting as her art. The idea, she says, is “to take serious things but to hold them lightly, with sincerity but lightly”.

Lee was born in 1954 in Brisbane, just as the White Australia policy was coming to an end—the same policy her family migrated from China to Australia under. She experienced the guilt of pursuing art within a migrant, working class background, alongside a lack of women artist role models, let alone a woman artist of Chinese heritage.

After a decade of graphic design work and teaching, she flew into art. She was greatly influenced by a 17th century painting that has affected so many women artists, Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes, and she soon became known for her photocopied Renaissance portraits that questioned authenticity art historically, but also personally. “That was the perfect metaphor for me because I just felt like a bad copy of white Australia and Chinese [culture], and I could never be authentic.”

In the 1980s things began to change. Lee started understanding her Chinese heritage through Taoism and Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism, where her Chinese-Australian identity met vast ideas of the self, materiality and being. “There’s always this sense of split, of how do I even exist? I feel like such an anomaly,” recalls Lee. “It was so painful, so painful. I had no option but to figure it out.”

“That wound is your connection to the world. Because where your heart is broken is where you’re most vulnerable and weak, and how you can feel most connected.”

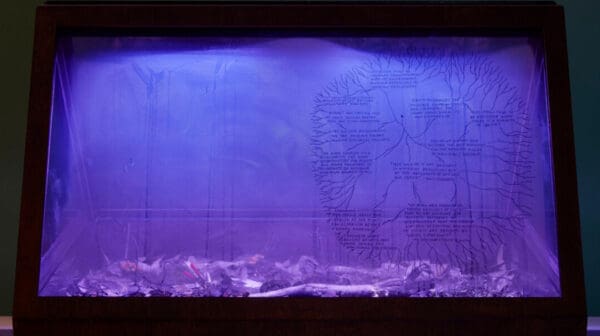

As the philosophy and personal enquiries shifted, so too did the forms. Family photographs became the cornerstones of artworks, most notably one image of her mother, father, eldest brother and aunt, all walking towards the camera. “The poignancy of this moment,” explained Lee a few years ago, “is this is my dad’s last day in China.” Her father is boarding a boat to Australia. Yet because of White Australia policy restrictions, Lee’s pregnant mother will remain in China, not knowing when she will see her husband again. “It’s a moment that is so fraught with anxiety and uncertainty and yet there is hope, because a migrant’s story is really one of hope, of trying to find something better, and that to me is part of what happens in this seamless tomb.”

The Seamless Tomb was not only a Zen proposition about locating freedom in the metaphor of a tomb, but was also the title Lee gave to an exhibition of her beguiling, famous bronze, paper and metal artworks, littered with small perforations. It’s a shimmering, otherworldly spectacle. “The question of who am I became a bigger question, much more expansive,” she said recently. “What is that I am? What is it that exists? . . . You extend into the world and the world extends into you, so you’re limitless in that sense.” The test of art making is harnessing materiality and concept to meet statements like that, to evoke the personal in materiality itself, a circularity that pervades Lee’s art.

Pivotal was the desire to start burning things, to make artworks with myriad small holes, which happened around 15 years ago. Lee followed an instinct to solder perforations into metal, to pierce holes into paper. It felt like the truth. Like an interpenetration of the realities of being Chinese-Australian. For Lee it was also a burning of self-delusions and self-aggrandising thinking, so that what remains is this: “All that you are is just what you are, it’s as simple as that.”

For Lee art making is a gesture of articulating and working through her darkest wound, that of being Chinese-Australian. “This deeply buried pain, which we all have by the way. If people relate to my work, it’s because that person has felt it in their own existence,” she explains. “That wound is your connection to the world. Because where your heart is broken is where you’re most vulnerable and weak, and how you can feel most connected.”

Unearthing this wound through art saved an even worse kind of repetition. Lee is fond of the haunting, almost comedic, honesty of Carl Jung’s famous quote, “Everything repressed returns as fate.” This history of the perforations, which abound in Ouroboros, can be easily imagined through her public artworks like a dazzling, perforated oval sculpture that sits outside the Museum of Contemporary Art, or the galaxies she’s created through myriad fire-produced holes in metal. Under the shimmer lies a turbulence. Holes are like small wounds, creating absence in presence, repeated so much it begins to look like the cosmos.

Lee once spoke about American abstract painter Mark Rothko in an interview with Liz Ann Macgregor for her 2020 survey at the Museum of Contemporary Art. She said, “One of the touching things about Rothko is that he wanted to be the greatest religious painter of his time. He was facing the same kind of dilemma that I was: the great religious paintings had already been done. What else could he do? So, he had to invent this new language.” What an awesome task. It’s unjust to call Lee’s work religious, but there’s the depth of revelation, or, as Lee says of Rothko’s minimalism and conceptualism, “an attempt to understand the essence of being human”.

When collective spaces for revelation and ritual feel ever-dwindling, art, in whatever form, in its most utopian guise, fills a longing between the private and communal—a way for receiving and sharing belief, for gesturing to something other than. As curator Helen Molesworth has written, what unites art and faith is the simple fact that “I believe in things I cannot prove are true.” She continues that “without a framework of belief, there’s only cynicism. And I cannot abide cynicism.”

If Molesworth is reclaiming art as a site of belief (and love and freedom), viewers become witnesses to, even part of, Lee’s own beliefs, meeting Lee’s revelations in art that are underpinned by spiritual experience. Lee is blunt on this: “My art is about experience.” And Ouroboros is about “the experience of cosmos”. Lee first started imagining infinity shapes, drafted with hose pipes from Bunnings, before settling on the ouroboros shape, with viewers walking into a kind of perforated chamber. The industrial nature of the metal turns fragile when morphed by hands, holding small holes, or, as Lee says, “kissing the metal with stardust”. It’s a dance between “solidity and dissolution”. In its position as an artwork, it also answers an urgent question Molesworth asked about curating itself: “Can we install works of art in ways that permit us this complicated realm of feelings and associations rather than in ways designed to hold such anxieties at bay?”

In offering something beyond the bland consensus of experience under consumerist life, Lee delivers something more difficult where emotional lives are shared lives, bound up with our being, politics and morals. Yet what’s changed in contemporary times is that experience was once so alluring precisely because of its prohibition—now one is encouraged to experience everything, all the time. Experience can suddenly turn barren, unsatisfying. From its materiality to its subtle demand for vulnerability, Lee’s work cuts through to the biggest experiences of life, belonging and unbelonging, being and nothingness, life and death. It’s an experience that’s almost an anti-experience, an antidote to the onslaught of a demand to always experience, a kind of surrendering—if you’re willing to go there.

Artists have a special public role of doing this thinking for the rest of us, and the thinking never quite escapes the wound—but there is a spirit of repair. As Lee said towards the end of the writing workshop, having lived seven decades, “I now realise there was not one single moment in anybody’s existence, let alone mine, where there isn’t belonging. Because damn it! You exist, you belong. It’s as simple as that . . . It’s really profound, and it’s really the hardest place to inhabit.” There was a great pause. One of the young writers replied, “Thank you, Lindy, that was fucking awesome, thank you so much.”

Ouroboros

Lindy Lee

National of Gallery of Australia

25 October – 1 June 2025

15 May – 14 Jun 2025

This article was originally published in the September/October 2024 print issue of Art Guide Australia.

To coincide with the unveiling of Ouroboros and the opening of Lindy Lee’s self-titled exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, the artist’s pure-gold work Abundance also joined the institution’s collection on long-term loan from the Pallion Art Collection. For more information, pallion.com.