Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

For generations, popular culture has presented motherhood as a time of sweet contentment and effortless joy. Yet in reality, the transition to becoming a mother can be wrought with physical and emotional upheaval, bringing about seismic shifts in the body, identity and sense of self.

There is a label for this time in a woman’s life: matrescence. Encompassing pregnancy and birth, and recognising the gravity of this time. Matrescence was initially coined by medical anthropologist Dana Raphael in the 1970s. While the term has been in existence for over four decades, it was not until recently that Melbourne-based artist Lillian O’Neil began exploring it in her work.

“I first came across Dana Raphael’s term matrescence on the wall text for Ying Ang’s photographic series, The Quickening,” she says. Exhibited at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in 2023, The Quickening contained grainy images captured on Ang’s baby monitors and photographic portraits of intimate moments postpartum. “At the time, I had a six-month-old and a two-year-old and it resonated with me,” O’Neil continues. “I related to Raphael’s idea that matrescence is a rite of passage, a period in which huge shifts of identity occur.”

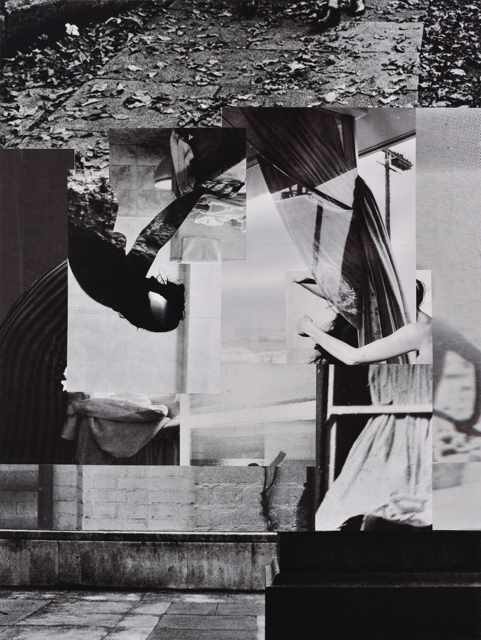

In a body of work originally commissioned for the 18th Adelaide Biennial of Contemporary Art: Inner Sanctum, O’Neil has used collage to explore ideas of matrescence and the split self. “I didn’t experience having a baby as a comfortable shift of identity into motherhood but more of a fracturing or splitting of self. Finding people who have written or made art about their experience of early motherhood was validating and helped me find my own way in to making work about it.”

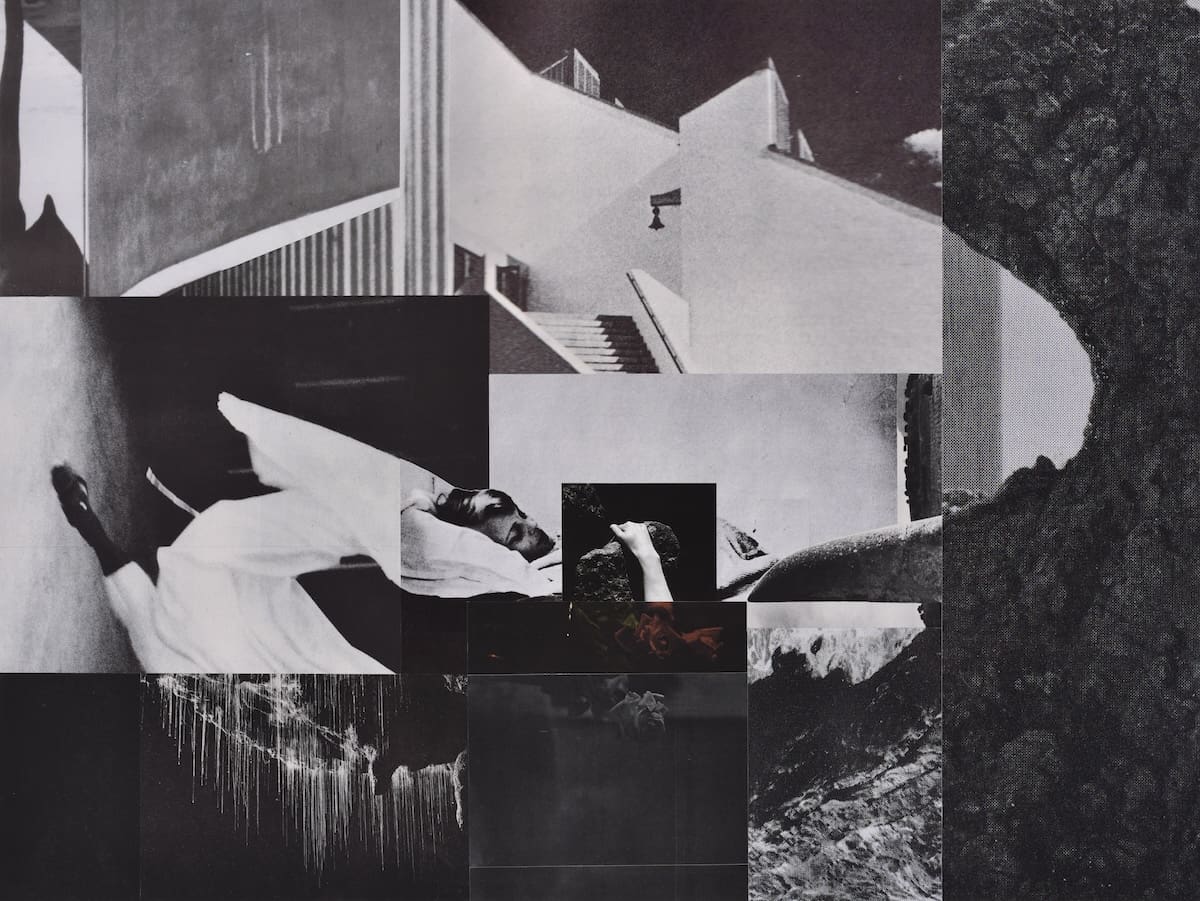

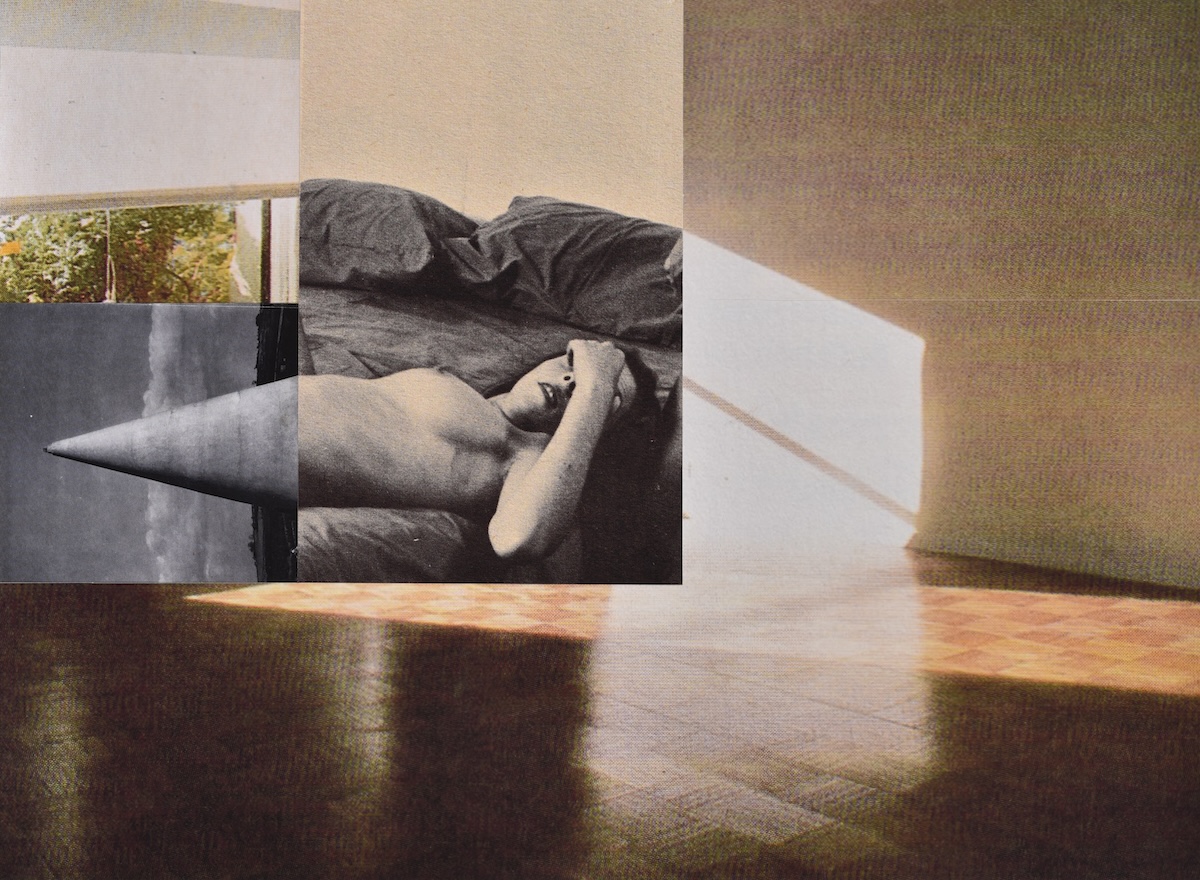

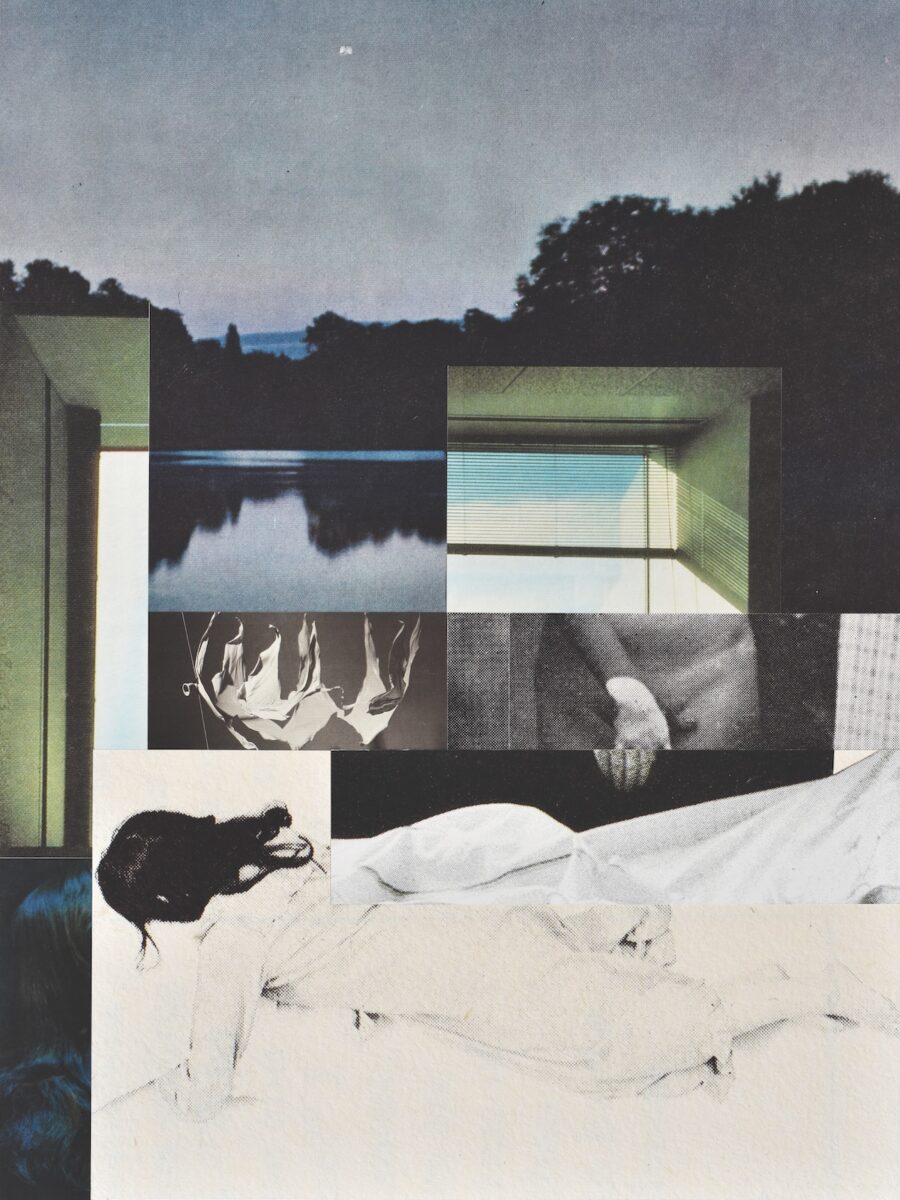

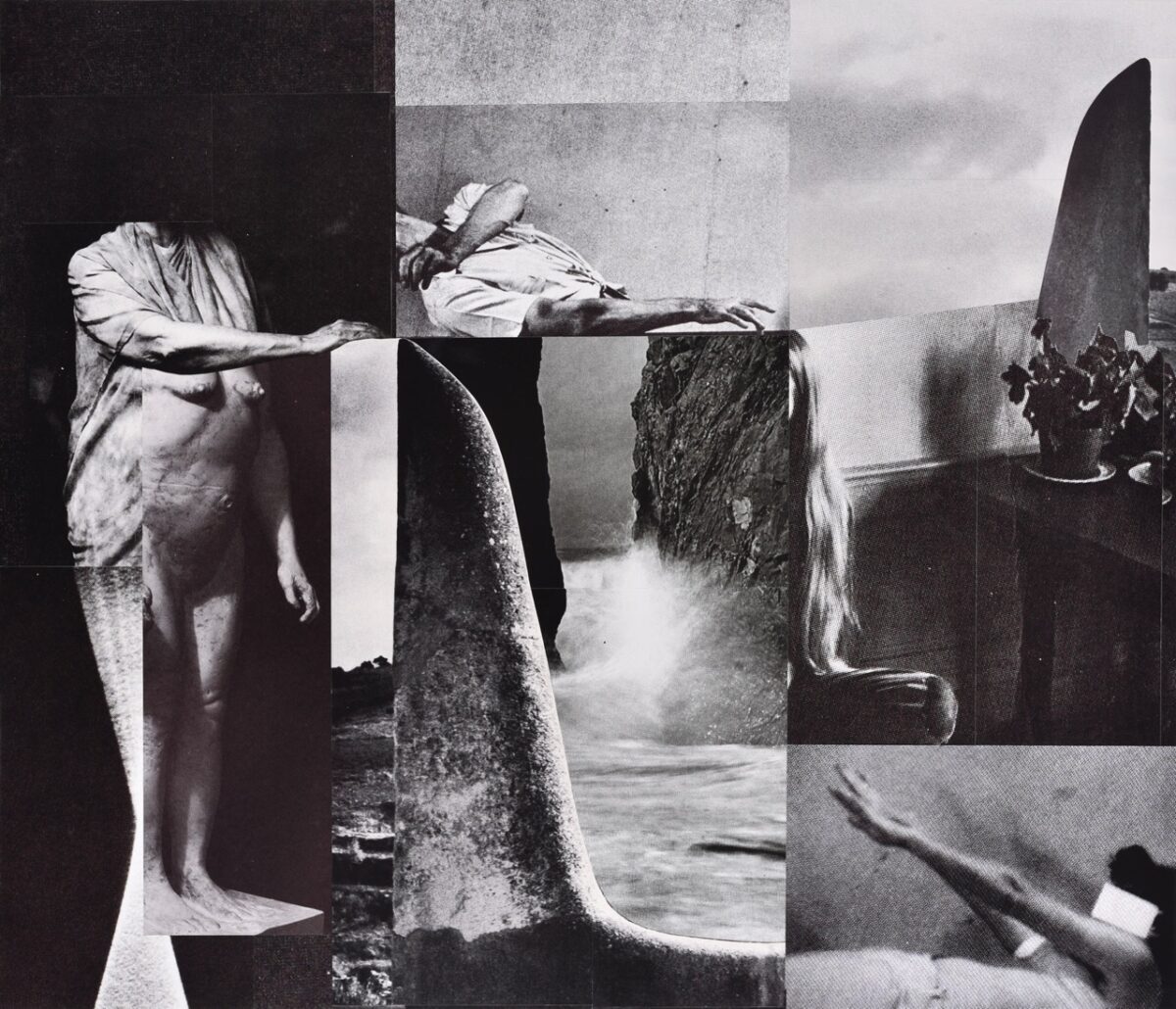

Assembling her multi-layered images from visuals found in vintage books and magazines purchased from op shops and secondhand bookshops, O’Neil often chooses images depicting the female body in architecture, mythology, and historical accounts of childbirth. Most of her finished pieces are black-and-white and on a large scale, alluding to the sense of overwhelm that comes with the early days of motherhood. In The light that spills across the ground between shadows, several new, smaller works add to the idea of the split self with disembodied limbs blending into the woven textures of clothing and wallpaper found within the domestic interior.

For O’Neil, collage is an apt medium to illustrate her experiences of matrescence. “I often felt like I was merging with my domestic environment and that time was moving in strange ways,” she explains. “Collage has an ability to combine fractured time periods, to coalesce disparate spaces and moments, and merge fragmented bodies with architectural spaces.”

To express the feelings of vulnerability and containment, many of O’Neil’s female protagonists are in varied states of laying down, sitting, or bending. In The place we dissolve, 2023, a woman is slouched in a chair within a domestic interior. Opposite is a window covered with horizontal blinds, reminiscent of a barrier between her and the outside world. She appears tethered to the interior, bound by the domestic sphere. Behind her is the partially obscured head of a bridled horse, a symbol of wildness contained. In the catalogue essay for Inner Sanctum, curator José Da Silva observes, “Fragments of rocks from caves and tunnels, which appear to cradle and enclose figures, reflect a sense of the women retracting into themselves.”

Night is a time O’Neil references frequently in her work. Despite being in the constant presence of a new baby, when darkness falls, feelings of physical and emotional isolation can be heightened. “Being awake breastfeeding through the night made me very conscious of the light shifting,” O’Neil says. “I lay awake for months, with no more than an hour’s sleep at any one time, and I would watch the night through the window, the moon arch across the sky, the first light of day, the stars through the tree—it was very quiet and very solitary.”

Also alluding to the shifting of light and shadows is the title of O’Neil’s exhibition. It is lifted from a passage in Annie Ernaux’s book Les Années (The Years). The author combines autobiographical details with French history, and one can see the connection to O’Neil’s work as Ernaux writes, “The distance that separates past from present can be measured, perhaps, by the light that spills across the ground between shadows, slips over faces, outlines the folds of a dress—by the twilight clarity of a black-and-white photo, no matter what time it is taken.”

Working with curator José Da Silva to develop her work for both Inner Sanctum and The light that spills across the ground between shadows, O’Neil says this ongoing support has been invaluable. “I had a coffee with José early on and I think he picked up I was going through something big,” she says. “I wasn’t even sure I was going to be able to make anything, and I’d just be staring at the studio wall blinking.” The result of this raw and profoundly emotional experience not only adds to O’Neil’s impressive oeuvre, but also sheds light on what can be a joyous, yet deeply challenging time in a woman’s life. As she puts it, “José installed the works and when I saw how he’d lit them, I felt that sweet spot of embarrassment, of having revealed something that maybe others might recognise in themselves.”

The light that spills across the ground between shadows

Lillian O’Neil

UNSW Galleries

28 June—8 September

This article was originally published in the July/August 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.