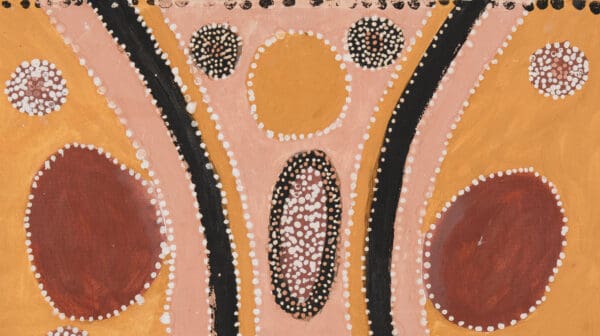

maḻatja-maḻatja (those who come after), a new exhibition by Betty Kuntiwa Pumani is so alive and intricate, it draws a sharp inhale on first encounter. Across the survey at Bundanon Art Museum, swirling networks of circles, sweeping arcs, and fine, thread-like lines spread across each canvas. The paintings hold together with a strong, steady rhythm.

Many are packed with concentric circles, some bold and solid, others soft, wobbly, or loosely scattered. Colours shimmer: deep purples, fiery reds and burnt orange for hot, sandy earth; cobalt blue for rock holes and creeks, lifted by dapples of white and pale yellow. The creamy yellows signify the clay cleaned from the waterholes by women and smeared on their bodies for ceremony. The crisp white alludes to the maku (witchetty grub) and mingkulpa (tobacco flower) that bloom in abundance after rains.

The exhibition labels resonate with a common refrain: nearly all of the works are titled Antaṟa, the name of the Country of the artist and her mother in the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands. Located in the north-west of South Australia and approximately 645 kilometres south of Alice Springs, Antaṟa holds the Tjukurpa songlines of the Pitjantjatjara people.

Antaṟa stretches from the base of the Everard Ranges, across a vast semi-arid expanse of 846,000 hectares. The broader landscape is marked by rounded granite hills, sparse scrub, and red, open plains. With a lineage that predates any attempt to map or measure it, Pumani notes that Antaṟa has no fixed borders.

The artist’s knowledge of this place is so precise, it is easy to compare her paintings to a map. Indeed, the late Aṉangu artist Kunmanara (Mumu Mike) Williams famously wrote ‘mapa wiya’ across a map of Australia. Translated as ‘no map’, the phrase is shorthand for an understanding of Country that transcends Western cartography. Pumani’s paintings reveal more than terrain. For Aṉangu, boundaries are shaped by story, not survey.

The works within maḻatja-maḻatja reflect the Tjukurpa songlines that cross this Country, specifically those connected to a significant rock hole where women perform inmaku pakani, a dance ceremony associated with the maku or witchetty grub. “The story I have painted is the very important law of Antaṟa,” the artist says in the accompanying monograph, “My mother would always tell me, ‘You can paint this story. This

story is vital and true.’”

“There is no word for ‘artist’ in Pitjantjatjara,” wrote senior elder Yatjitja David Miller in 2010. “Painting has only happened recently, so we say ‘Painta milipai’ (using the English word)—‘He’s painting.’” For Pumani, painting is an extension of her role in the community as a ngangkari or healer, and cultural authority. The precedence of these cultural responsibilities was underscored by the artist’s unexpected absence from the opening of her first major museum survey exhibition to attend to ceremony at home.

With a title that means ‘those who come after’, the exhibition embodies Pumani’s responsibility to both honour and repatriate her intimate knowledge of Country. Pumani tells her story in the exhibition’s accompanying text: “I am very proud of the Maku story and of keeping our grandmothers and grandfathers strong by sharing it. I am glad to be able to pass it down to the younger generation now, teaching them and

showing them everything that needs to be known.”

The paintings on display at Bundanon, made between 2012 and now, form a small part of a much bigger living archive on Antaṟa. The archive is embedded in the land and embodied by those who enact its stories. Country “is not just ‘land,’” Kullilli and Wakka Wakka scholar Max Brierty wrote in 2024, “but a relational matrix, comprised of Law, places, spirits, people, animals, plants, fungi, matter and energies.”

As Gumbaynggirr and Wiradjuri curator Margo Neale put it in 2017, landforms are “terminals to which only a few archivists have the password.” Pumani is among the Antaṟa archivists, creating paintings embedded with songlines, ceremony and place.

The inclusion of works by Pumani’s daughter, late mother, and sister in malatja-malatja highlights the collaborative nature of her practice. Four of these works are drawn from the Mimili Maku Arts Cultural Collection, a recent initiative aimed at keeping cultural material in the community.

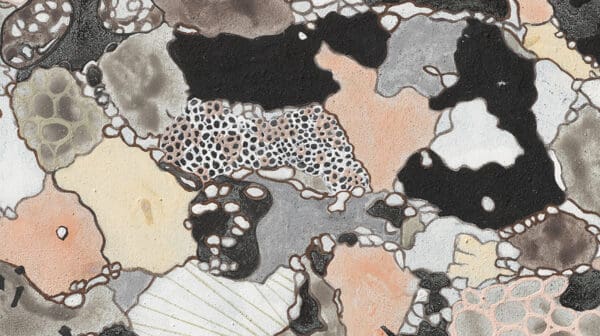

Two equally scaled canvases hang side by side, perfectly aligned to depict the same site. One, by her daughter Marina Pumani Brown, is underpainted in black and stippled with sunset oranges and burnished reds. The other, by Betty, features her signature cobalt blue underpainting. Together, the connecting lines of the Maku songline reflect the enduring interconnectedness of the matrilineal line. While each family member brings a distinct visual language, the Tjukurpa of Antaṟa reverberates.

The exhibition’s centrepiece is a monumental diptych: it is the only work that Pumani created in isolation. Commissioned for The National 2021: Australian Art Now and produced during the COVID-19 lockdowns, the work spans 10 metres across two canvases, both stretched onsite at the museum. It bears the imprint of the artist’s body, seated on the canvas in a daily vigil of painting sustained over many months. Every mark is stippled using a small wooden stick, “like I was taught”, says Pumani.

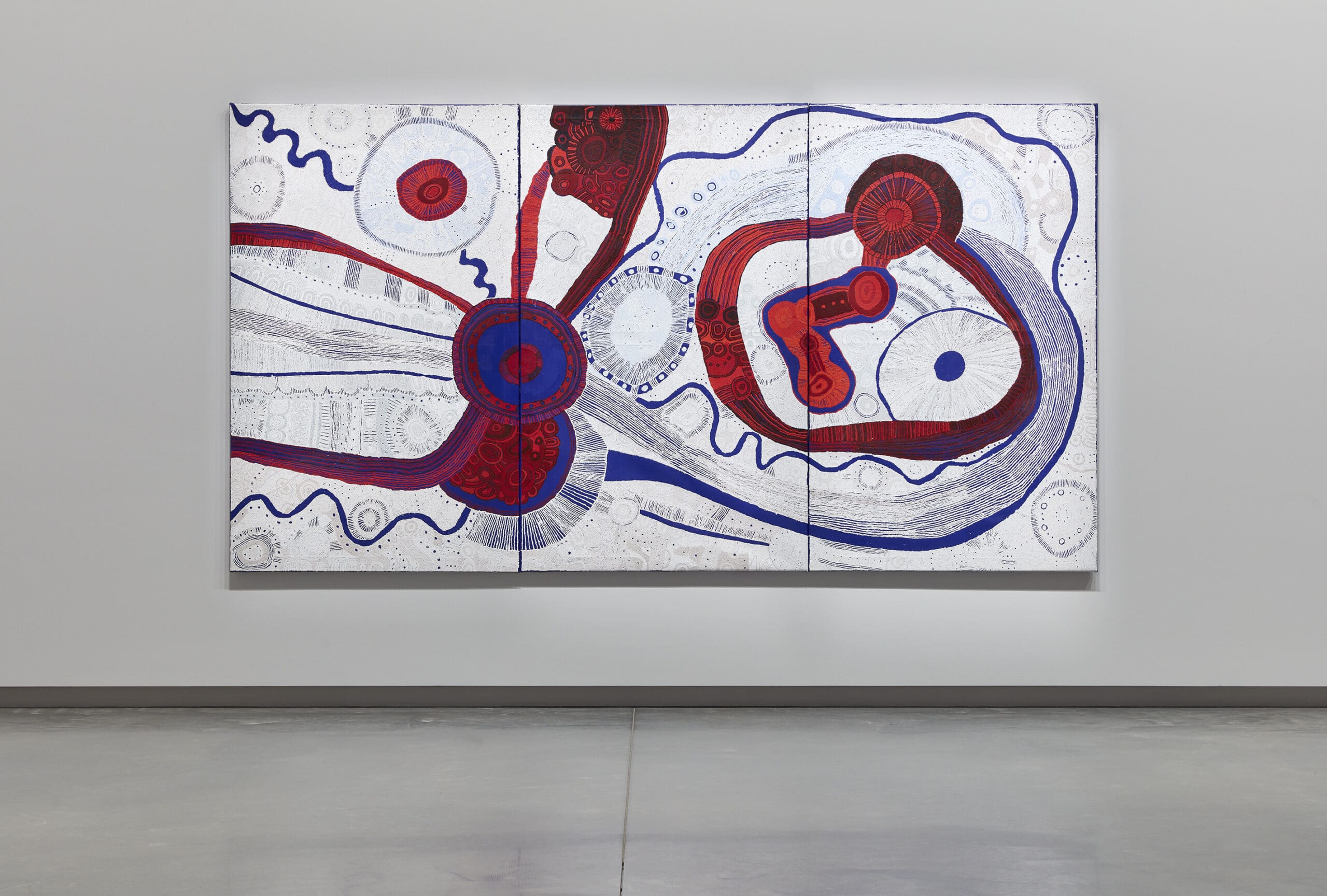

More recent works by Pumani reflect a shift in the artist’s palette, with increased use of flecked whites. Among these is a triptych, commissioned by Bundanon, and displayed in the far corner of the exhibition. Not only titled Antaṟa, it is also imbued with its namesake. An adjacent video tracks the work’s journey, with the artist, from Mimili Maku Arts Centre where Betty works, to the very site it depicts.

Displayed far from its source, Bundanon hosts a resounding story of matrilineal lineage. Though generously shared, these stories are not specifically meant for gallery visitors. They are created in homage to ancestral knowledge and to safeguard against its loss. Offering a statement for her exhibited work, Betty’s late sister Kunmanara (Ngupulya) Pumani explained what they say to their children: “This is a Dreaming, later on into the future you will look after it and keep on looking after it. This place has a really big Dreaming, your Dreaming, and for generation

after generation, after generation, after generation, after generation it will be yours—it will keep on going—it will go out and onwards.”

Betty Kuntiwa Pumani:

maḻatja-maḻatja (those who come after)

Bundanon Art Museum

(Illaroo/Wodi Wodi and Yuin Country NSW)

Until 5 October

This article was originally published in the September/October 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.