Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

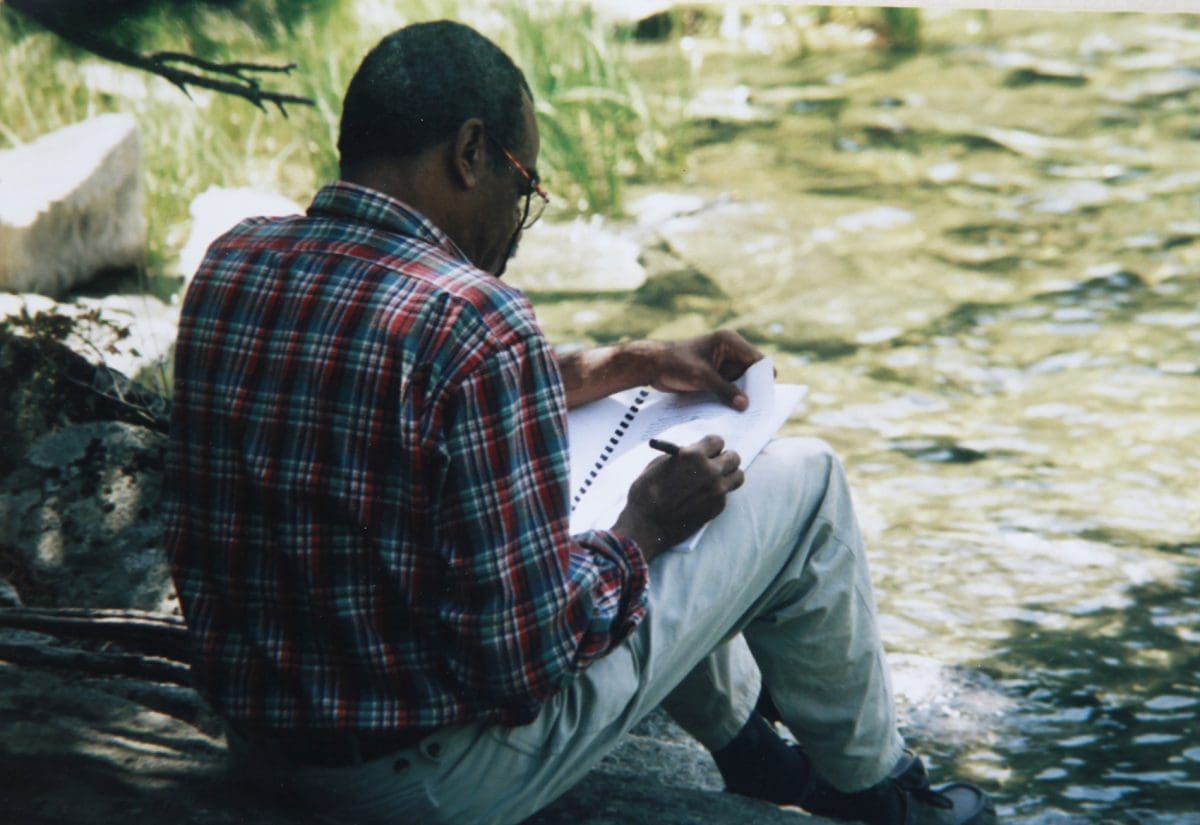

For American artist Asad Raza and swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, few writers speak to our cultural moment as poignantly as Édouard Glissant. In Glissant’s seminal 1990 essay, Poetics of Relation, the late poet and philosopher, who was born in colonial Martinique (a Caribbean island), worked to liberate the West Indies from French rule. He explored ideas such as the ‘right to opacity’ which argued that those who come from oppressed histories or positions should be allowed to maintain the power of opacity; to not be forced to be completely understood.

Also important was the concept of creolisation, which can be described as being in a constant state of cultural transformation: it’s is a term that originated in the Caribbean to describe the way that different cultures shape each other to create a new culture.

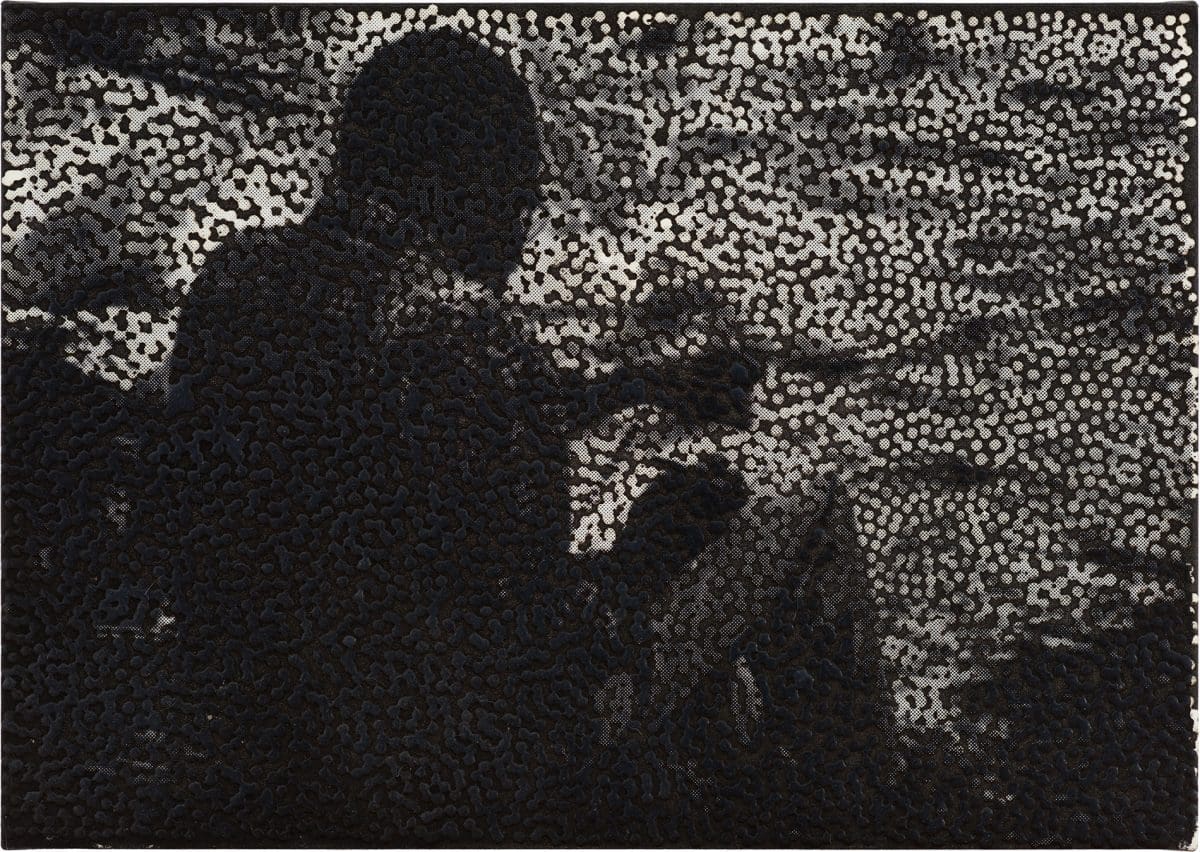

Glissant’s belief that identity is always in flux, shaped by exchange and synthesis between cultures, is a powerful corrective to a world that’s increasingly fragmented and polarised. It’s also the focus of a new exhibition This language that is every stone at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art (IMA). The show pairs Australian First Nations and diasporic artists—such as Megan Cope, Sancintya Mohini Simpson and Daniel Boyd—with international contemporaries like Anri Sala and Philippe Parreno.

The exhibition’s three curators—Raza, Obrist and Kamilaroi artist Warraba Weatherall—speak to Art Guide about curating identity in the 21st century, the relationship between art and language, and how Glissant’s writing resonates in an Australian context.

Neha Kale: A lot of contemporary cultural conversation reduces identity to a commodity, and difference to a fixed entity. It’s a worldview that often restricts artists of colour. But this position is countered by the ideas of Édouard Glissant, which is a springboard for This language that is every stone. What are some of the challenges of curating shows around cultural identity in the 21st century?

Warraba Weatherall: The biggest challenge in my experience as an artist and within curation is the expectation to be understood by an audience. Sure, this may be reasonable to a certain extent, but often culturally diverse practitioners and their work are reduced and simplified to make it both understandable and palatable. Glissant termed these dynamics as ‘opacity’ and ‘transparency’, where the artist has a ‘right to opacity’, The artist is not required to divulge all content for a culturally illiterate audience. These concepts resemble the right to self-determination within the Indigenous context of Australia.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Glissant has always been a toolbox for me. He raises many questions about globalisation, the local and the global. In relation to the identity question—the idea is to unthink identity as [about] singularity, fixity or purity. The key idea from Glissant is that we have to admit that our identities depend on others.

At the moment, we have all these localisms and nationalisms in the world which have been exacerbated by Covid. Glissant is a very formidable antidote to that. His [ideas] around archipelagic thought makes it possible to say our identities are established, but we can change through an exchange with others without diluting our sense of selves.

Asad Raza: I think we’re seeing a series of currents in the geopolitical order that were already in motion 30 years ago, but [have become] more visible in the last 10 years. [This] is basically a return to a certain kind of essentialism about the fixity of identity. These were dangers that Glissant was very aware of in the ‘70s and ‘80s and was writing about in the ‘90s. I think there was a period between the late ‘90s and 2001 where people seemed to think that those problems were going to go away. Instead they came back with a vengeance. The tools that Glissant developed suddenly appear to be extremely prescient. What’s interesting to me about his work is that the longer time goes by the more relevant his work seems to become.

Glissant’s way of theorising identity is as someone who comes from the archipelago of the Antilles. [He] believed that culture is not fixed and immutable, like a massive continent that doesn’t change. His metaphor is of the archipelago where each island has a distinct but linked culture. His way of thinking about identity for individuals is informed by that. So, what you have is a recognition of difference within shared bonds.

NK: Australia is a settler colony shaped by many histories—including 60,000 years of Indigenous sovereignty, the tides of British colonialism and waves of immigration. But in Australia, cultural discourse still focuses on reductive ideas about otherness. This is the fourth in a series of exhibitions that Hans Ulrich and Asad have curated around the work of Glissant. How do you think his ideas speak to an Australian context?

WW: I believe Glissant’s ideas are powerful within Australia because his way of breaking down concepts of culture and identity are insightful and demonstrate the depths of identity formation. If Australian school curriculums gave students the critical writings of Glissant, Fanon and a myriad of Indigenous and diasporic writers, instead of simply attaching culturally diverse content to a Eurocentric paradigm, future generations of Australians would be better equipped to live in a multicultural society.

AR: Since 2018, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the Australian context, but my perspective is really not, “Oh, what can we teach this benighted place about the cosmopolitan richness of Paris and New York.” It’s exactly the reverse. When I first came to Australia, I was so impressed by the conversation that was going on about Indigenous and diasporic identity and cultural stewardship that was already happening in Australia. I was already thinking like, “Wow, there’s such an interesting discourse and it’s so far ahead of what we have in New York.” In New York, things like land acknowledgement are happening only now.

Australia just needs to pay attention to the work of Richard Bell and Sancintya Mohini Simpson and lots of other people—there’s no need for me or Hans Ulrich. But I was interested in bringing [Australian] artists into conversation with ideas that didn’t just come from an Australian context, so they could connect to conversations that are already happening in Martinique or Paris or Mississippi.

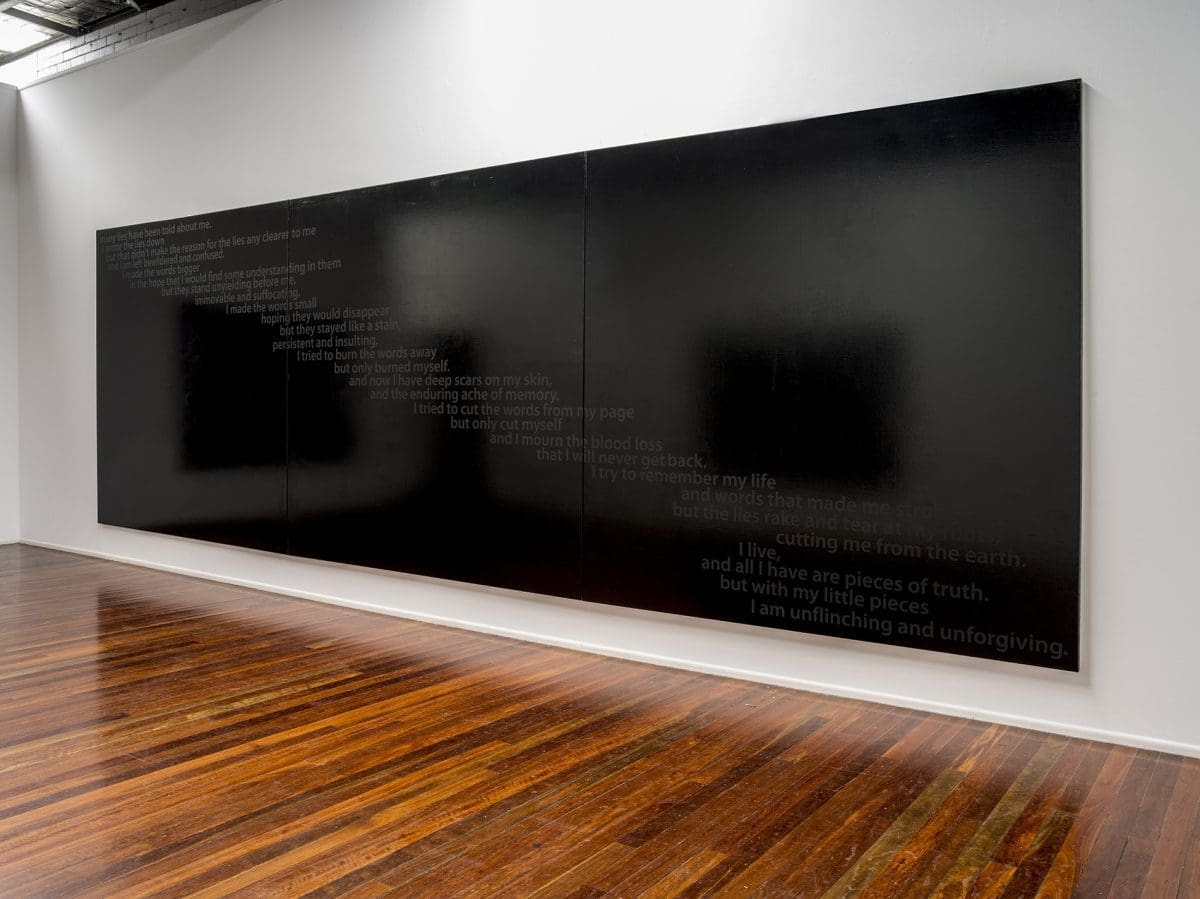

NK: The phrase This language that is every stone highlights the ways in which language can be a burden, a force that is homogenous—but Glissant’s ideas of creolisation focus on cultural transformation as an ongoing process. It’s a notion that drives many other artists in the show. How does This language that is every stone explore the tensions between the possibilities of art and the limits of language when it comes to thinking about cultural identity?

WW: The immediacy of the English language, through its own process of creolisation, is loaded with historical nuances which makes it difficult to communicate around cultural identities, without signifying its negative aspects. Even for someone like myself who is fluent in English as a first language, the difficulty in naturally explaining cultural beliefs or phenomena are met with caution due to complex histories.

For example, if I were to speak about cultural diversity—which has largely become Australian shorthand for ‘not-white’—we begin to see that even our use of language is structured around Anglo normativity. In a way, this can be mediated through visual languages by both the ambiguity and diverse understandings of different forms. Visual language and art support expansive and creative thought. This is the point of tension between the two, as visual language bypasses our inner projections of how we understand the world.

NK: What are some of the highlights of the exhibition, and which works grapple with ideas on culture and identity in unexpected or surprising ways?

WW: The selection of works from Phuong Ngo’s series Lost and Found, 2019, is incredibly hard-hitting, where his juxtaposition of archival materials work to contrast experiences in Vietnam and France. In considering the Vietnamese experience of French colonialism, the works question how colonial ideologies continue to influence how we determine value of people and community. Anri Sala’s work Làk-kat 2.0, 2015, is also a favourite. The two-channel film presents the artist with a young boy speaking in the Wolof language, who communicate French terms used to distinguish skin colour. The work can be seen as a direct presentation of creolisation, but it also demonstrates the subtle codification of speech which constitutes meaning of how words are spoken.

HUO: There are many people who just wouldn’t go to a museum and Glissant always told me that you need to create other forms of engagement or models of exhibition that are more mobile, that could go to the people. I was pleasantly surprised that many of these artists aren’t just working in the temporality of this exhibition. If we think about the environment, event culture isn’t sustainable. We need to think about how to liberate society, not how to pillage. I find it fascinating that several of the artists in the exhibition are developing such projects—related to farming, related to gardens. It made me extremely happy. In a way, this is not just an exhibition, it is a process that hopefully continues to grow and evolve.

This language that is every stone

Institute of Modern Art

12 February–16 April