Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

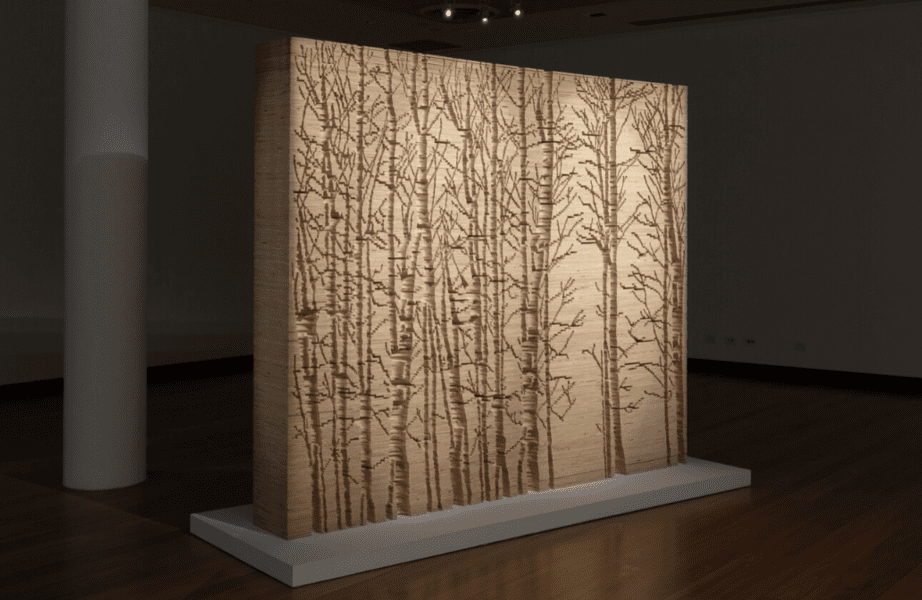

Kylie Stillman, Scape, 2017, hand-cut plywood, 200 x 240 x 30cm. Courtesy of the artist and Utopia Art Sydney. Photograph by Christian Capurro.

Kylie Stillman, Scape (detail), 2017, hand-cut plywood, 200 x 240 x 30cm. Courtesy of the artist and Utopia Art Sydney. Photograph by Christian Capurro.

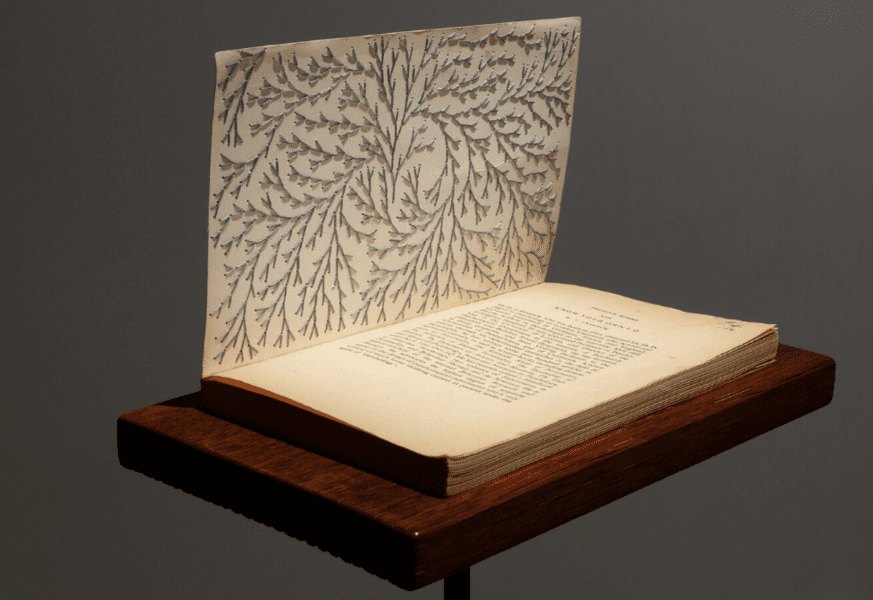

Kylie Stillman, Know your IQ, 2016, hand-stitched book, 15 x 12 x 19cm. Courtesy of the artist and Utopia Art Sydney. Photograph by Christian Capurro.

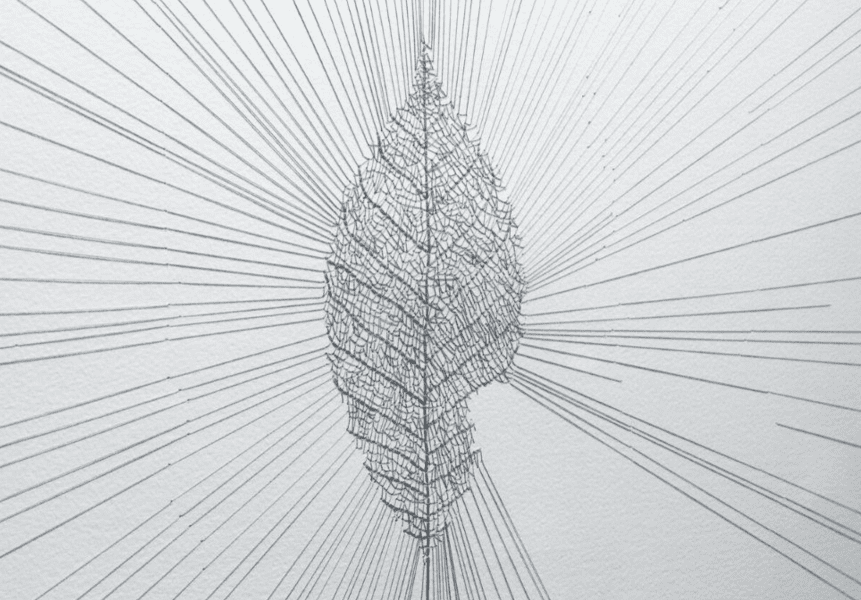

Kylie Stillman, detail from Leaf Margin, 2019, hand stitched work on paper, 76 x 56cm. Courtesy of the artist and Utopia Art Sydney. Photograph by Christian Capurro.

Kylie Stillman, Park Views 2003, hand laced Venetian blinds, 4 blinds, 180 x 95cm each. Courtesy of the artist and Utopia Art Sydney. Photograph by Christian Capurro.

Kylie Stillman’s silhouetted carvings of natural forms, such as trees and birds, are built up slowly over days and weeks, hollowed out from stacks of reinforced paper or timber with hand tools, knives and jigsaws. Her online exhibition, Not fully or properly either of two things, surveys 20 years of practice, through which Stillman has applied specialised carving techniques to venetian blinds, books and pickets, embellished with embroidery and found text. Sheridan Hart spoke to Stillman about the physicality of carving and the curious life of the library books she works with, especially as coronavirus restrictions continue.

Sheridan Hart: You’ve given your exhibition the poetic title Not fully or properly either of two things. Where does the phrase come from?

Kylie Stillman: Artists are commonly interested in spaces between things, whether physical or conceptual. I wanted to avoid the word ‘between’ and be more playful with that idea. The phrase comes from a dictionary, but it also speaks to how I feel about my work and myself as an artist.

SH: The word ‘properly’ is certainly loaded with connotations of formality and convention…

KS: It’s something I’ve often wondered about: the properness of being an artist who doesn’t use traditionally ‘proper’ materials like oil paint or marble. It’s something that connects all the works in the exhibition.

SH: Your work uses negative space to build up a positive image. In some pieces, several thousand divots or gouges have been made. How do you prepare for such an endurance process?

KS: You need to be comfortable, to have lots of time and space, not just for the work but to arrange your process around it. I have learnt you need at least three times the space that the sculpture takes up, because sometimes it’s in parts, or in piles, or being treated, and you need to physically move all around it. These movements require a lot of mental timetabling. You want to be economical, to build the work in the least number of stages, movements and studio arrangements.

SH: How do you manage the rhythm and repetition of this work?

KS: The time factor is interesting. One stitch or one jigsaw cut, whether big or small, takes about the same amount of time. I’ve found that small and large artworks can actually require the same time. It’s funny to think how little difference there is between a small work that fits on my lap and something that takes up the whole studio. The process often comes down to performing just one repeated mark; one stitch, one cut.

SH: There is a simplicity and regular shape to wood and paper. What goes into selecting and preparing these raw materials?

KS: My work Scape is made of 200 panels of plywood that are 2.4 metres tall. A piece like that goes through three stages before any marks are even made on it. It must have location holes marked into it. Every panel is discreetly numbered and sanded. And it has to be made structurally sound. My books are all rotation drilled and have internal mechanisms in place to keep them stable. There might be two or three weeks of handling every component individually and thinking through that process before carving starts.

SH: What a careful, tender process. What does it feel like when you finally begin to carve?

KS: It’s pure joy. I do love the minimalist and structural component of the work and in fact, with a work like Scape, it remains: one side is carved, but the other is left, perhaps waiting for something to occur.

SH: You also work a lot with paper, a material that is so easily marked with signs of use.

KS: Working with paper and books is so unique and rich. You have the benefit of its rigidity but the disadvantage that it’s a precious, delicate material and any bends or marks will be read as part of the artwork. It’s also physical: my body goes in and out of focus as I turn pages over and over. Sometimes I catch myself reading.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about the public life of books. The books from the exhibition are from Boroondara Library, who gave me unwanted books to work with, but at the moment, libraries are spaces we’re avoiding. I find it interesting that during Covid-19 the books have to undergo 72 hours of decontamination before being loaned again. They keep traces of previous borrowers: folded pages, the oil stains on the ends where two thumbs hold the pages open. We put them on our laps, take them to bed, on public transport, they’re thrown in a bag, even taken to the bathroom, all these things that we’re trying to avoid contact with right now.

SH: Does the text inside the books have a part to play?

KS: In my new work Verso, I’ve been working with a collection of 200 books across five bookshelves. I removed some words of the titles with a dark marker, leaving a selection that relates to nature or concepts of living: barb, gust, bone, falcon, robin, mother, bird, sand, light, ice, hill. The words are markers of what’s inside, but they tell stories in and of themselves too. I can no longer look at a bookshelf without mentally scribbling out words to make these non-poems! This is on one side of the books. On the other, I’ve carved a large flock of miniature birds, moving in a singular direction, disbanding or migrating. The work is installed [in Town Hall Gallery] in the same council building where the books were once borrowed by local residents.

SH: Do you anticipate that the paper might deteriorate or the work might become disarranged over its lifetime?

KS: The books might age slightly, go yellow or fade perhaps, but for me the work never changes because the shadows cast by the carving are always the same. The forms that have been removed persist. The exact part of the work that is not there is actually the most permanent part of the work.

Kylie Stillman’s show Not fully or properly either of two things can be viewed online here.