With a career spanning three decades, Adelaide-based Kirsten Coelho was the feature artist of the 2020 South Australian Living Artists Festival (SALA). Taking inspiration from the classical silhouettes of Greek and Roman ceramics and the robustly functional domestic objects of the 1800s, Coelho creates porcelain objects that marry expert technique to timeless evocations of functional forms. Despite numerous setbacks caused by Covid-19 restrictions earlier in the year, in July 2020, when Briony Downes spoke to Coelho about collecting, her love of museums, and how light can tell a story, the artist was looking ahead to a series of upcoming exhibitions and being the subject of a monograph.

Briony Downes: You create beautifully finished porcelain objects – most often beakers, plates and bowls. Can you tell me about the process your pieces go through before they reach completion?

Kirsten Coelho: There are multiple levels to my practice. There’s the day to day making, engagement with the different porcelains I use, the glaze materials, the kiln. Porcelain is a very compelling medium and also very challenging to work with. There is a lot that goes wrong with it, but I love the way porcelain enhances very subtle glaze colour. I work with five kinds of porcelain in varied tones of white and have found only porcelain can accentuate those fine variances of tone.

I feel like you could work with porcelain for 80 years and never conquer it. I’ve been working with porcelain pretty consistently for about 20 years and it still challenges me. I’m always trying to improve my skills and knowledge, so I can articulate what I am trying to say through objects. An important aspect of my practice is building a narrative for my work.

BD: As the featured artist of the SALA Festival, a selection of your objects is being shown together with Russell Drysdale’s 1949 painting, Woman in a Landscape, at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA). What is the narrative underlying this pairing?

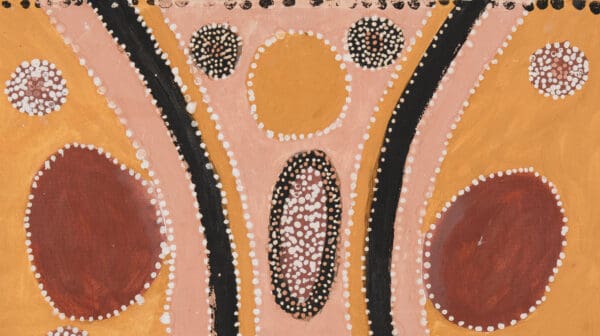

KC: All of the works in this pairing have been drawn from the AGSA collection. My work in SALA includes six objects from Transfigured Night, an installation first shown in Divided Worlds, the 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art curated by Erica Green.

Transfigured Night was made up of 73 porcelain pieces lined up on a 14-metre-long plinth and exhibited in a really darkened room. It took a cue from Henry Lawson’s 1892 story, The Drover’s Wife. What I remembered from Lawson’s story was this image of a woman and her children alone in the night, waiting inside their house for a snake to reappear.

In Transfigured Night, the way the porcelain objects were arranged and lit connected to how night can be quite terrifying, but day brings a new light. In a similar way, Drysdale’s painting speaks to those lived experiences of women living in isolation within the Australian landscape.

BD: How have those ideas been physically translated into the SALA exhibition?

KC: In the original installation, light played a really important part. I was lucky to have Geoff Cobham, a lighting specialist working in theatre, come in and do the lighting. He and his partner Chris Petridis built this extraordinary environment through light which made my ceramic objects seem as though they were momentarily floating in a dark space. I wanted the light to be similar to the first chink of sunlight coming through a door at sunrise.

BD: Domestic objects from different periods of history inform your stylistic approach. How do you go about finding the objects that inspire your work?

KC: I love looking at museum collections, that’s one of my favourite ways of researching. I find museum collections really fascinating because it’s a historical document of what has come before but often with the original context removed. In a museum, an object will be next to something completely unrelated to the time frame in which it was made – a setting incongruous to the object’s origin and purpose. I quite like that juxtaposition.

I read a lot. Literature, stories, poems. I also look at constructed narrative in painting and use that as a resource.

I’ve repeatedly used paintings as starting points for my work, especially those of Russell Drysdale and Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershoi.

BD: Why those particular paintings? Is it their subjects or the way they have been painted?

KC: It’s a bit of both. Sometimes it might be the objects in the painting or sometimes it’s the story portrayed. It might be the use of light and the way space is evoked through painting. Particularly with the Hammershoi works, they are very spacious and sparse, often interior views with directional lighting. I like to utilise that sparseness when I’m thinking about my own work.

In October, I’ll be exploring these ideas further in Ithaca, a large-scale installation at the Samstag Museum of Art. Ithaca was meant to be on during SALA but was postponed due to Covid-19 restrictions.

BD: You spent time living in London in the 1990s and in 2007, your work was included in a group exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), known for its extensive collection of 19th century domestic objects. Over time, have you found there is a particular collection you keep coming back to?

KC: The V&A is right up there, but one of my favourite collections in England is Kettle’s Yard. It’s a small museum in Cambridge which was once the home of Jim Ede and his wife Helen. Jim had been a curator at the Tate Gallery in London and they moved to Kettle’s Yard in the 1950s. Jim and his wife are no longer with us, but the house is open to the public. You can go in there and sit for a while. All the chairs are quite old as Jim and Helen collected them from different periods of history. There are beautiful old books and you can read them. There are ceramics by Bernard Leach and Lucie Rie. It’s a beautiful experience going there. It’s one of my favourite places and I’ve been there about four times now, I love it.

BD: Ideas about collecting and the meaning we give to treasured items contribute to the overarching themes of your practice. What is it about a cluster of objects that appeals to you?

KC: I really love the incongruity of objects together because that is what happens in a home. It’s not necessarily a curated space, you might have something your mother gave you next to something bought in an op-shop, or something quite antique and old. It’s all different things together. I’m always fascinated by the eclectic nature of collecting and the stories attached to those objects.

In addition to SALA and the exhibitions below, Kirsten Coelho spoke about her practice in an AGSA Tuesday Talk podcast.

This article was first published online in August 2020.

Ithaca

Kirsten Coelho

Samstag Museum of Art

16 October – 18 November

Kirsten Coelho: New Work

Philip Bacon Galleries

10 November – 5 December