In 2004, an Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition of Man Ray’s works drew a record 52,000 visitors. One of them was Lesley Harding.

“It was beautifully curated,” says Harding, now artistic director at Melbourne’s Heide Museum of Modern Art. “It really stuck with me.”

That show proved to be the seed of an idea that matured over a generation: Man Ray and Max Dupain, now on display at Heide. The exhibition brings together more than 200 photographs—some never publicly shown—from Australian collections and private loans from Paris, staging a dialogue between two modernist visionaries, a world apart yet connected by surrealist experimentation.

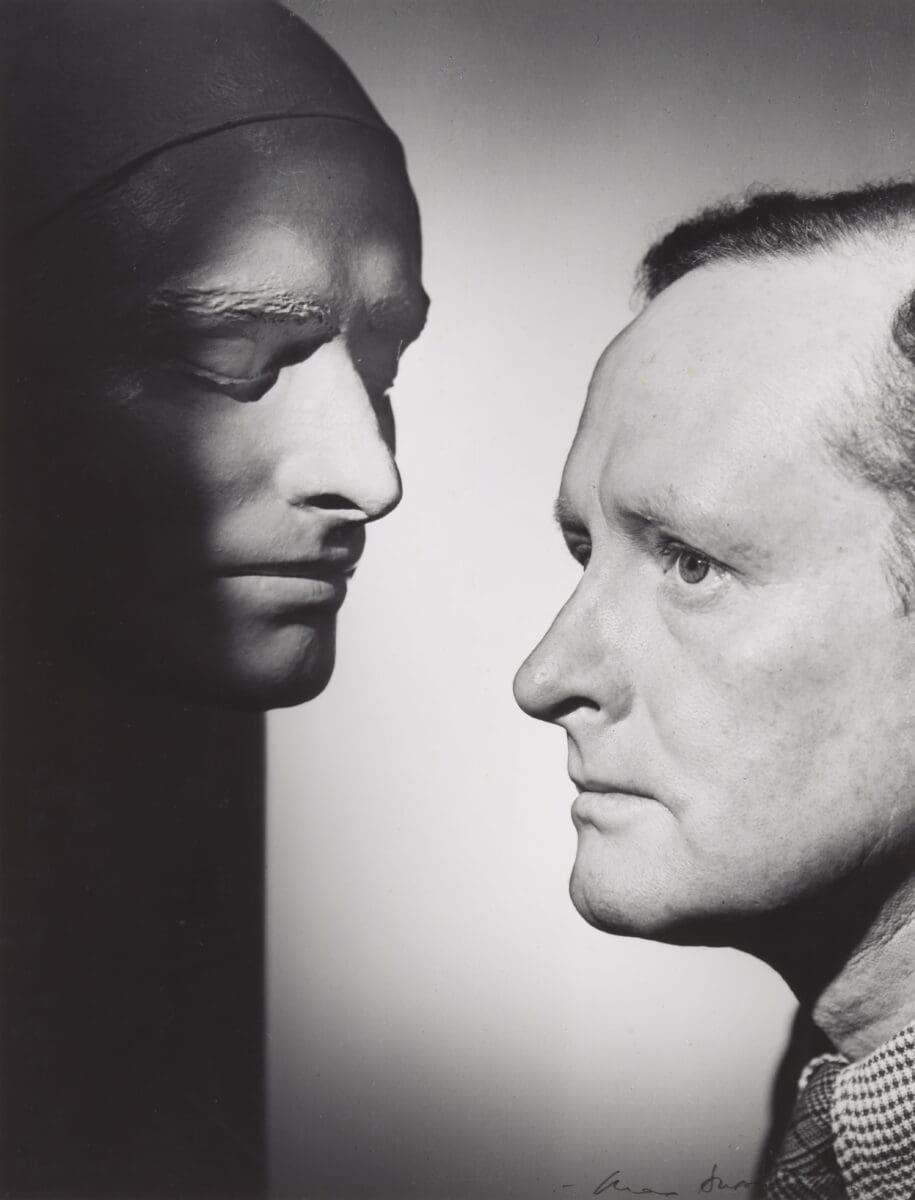

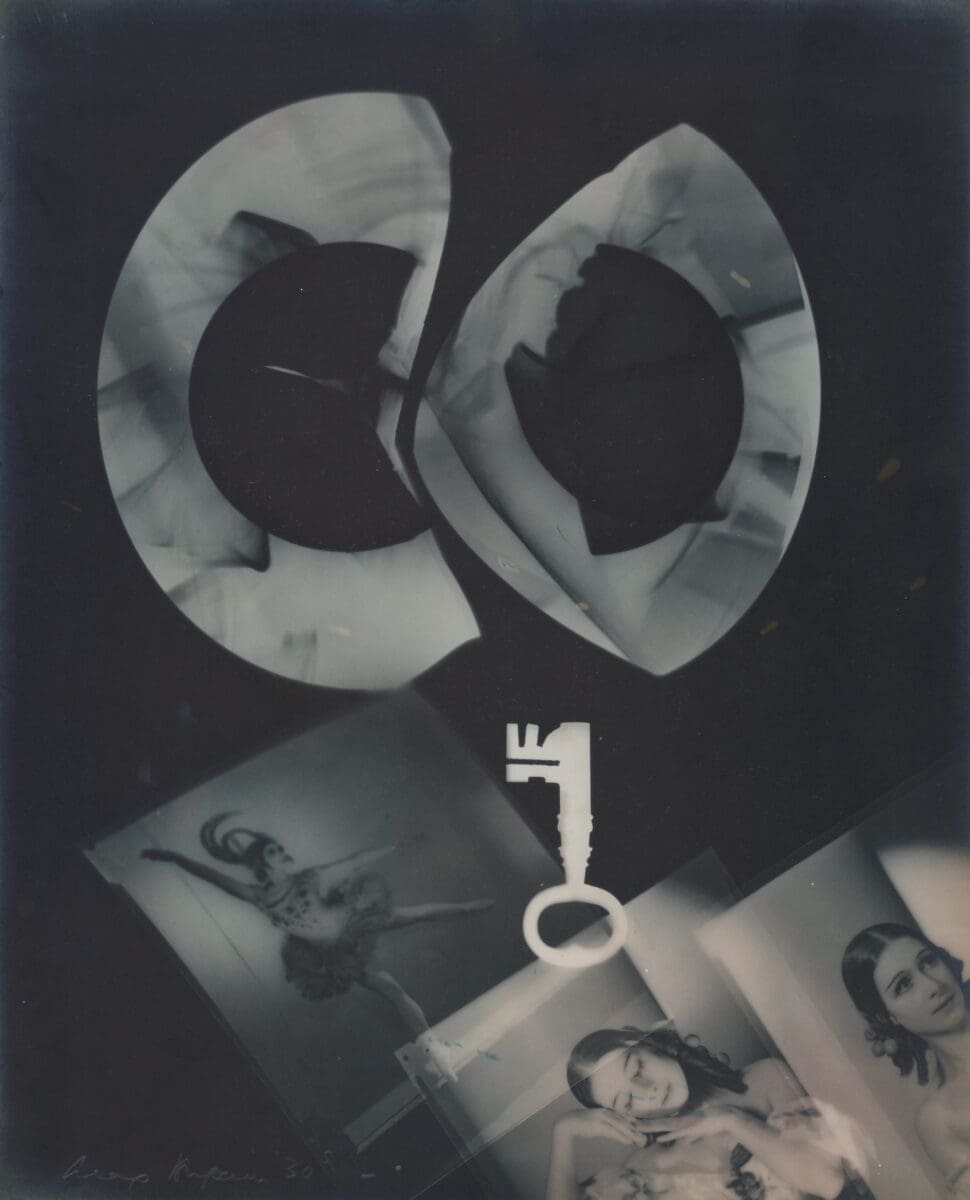

Man Ray was a global icon of surrealist photography and Dadaism, redefining photography as an art form. His trajectory can be put down to several factors – his talent and tenacity, for certain. But he also happened to be in the right place at the right time. In 1921, he relocated from the U.S. to Paris. Though Man Ray’s works now command high prices, it wasn’t always so. At first, he struggled to sustain himself, moving between portrait commissions, fashion photography and avant-garde experimentation. His portraiture, on display at Heide, shows the company he kept as he became entrenched in Paris’s elite art milieu: artists like Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso, and writers like Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein.

“We could have done a solo show of Man Ray,” Harding says, “but it was important to look at what was happening in Australia at the time.”

Enter Max Dupain, who flirted with surrealism but, as Harding points out, “refused to be defined by it”.

In 1920s and ’30s Australia, photography was soft and decorative, echoing the British pictorialist tradition. Dupain became a formidable force in the shift towards new photography, elevating the photograph to an artwork rather than just a painterly imitation. He came of age as post-colonial Australia was still defining itself. As Surrealism challenged artistic norms abroad, European writers and artists were reimagining what art could be. Dupain—though geographically distant—wanted to be part of that zeitgeist. He wasn’t a traveller until later in life, so gleaned what he could about global surrealist trends from foreign magazines and journals.

“The great thing about photography is that the images tell you everything,” says Harding. “He didn’t need to read the German or French in those magazines. He got all he needed from looking at the photographs.”

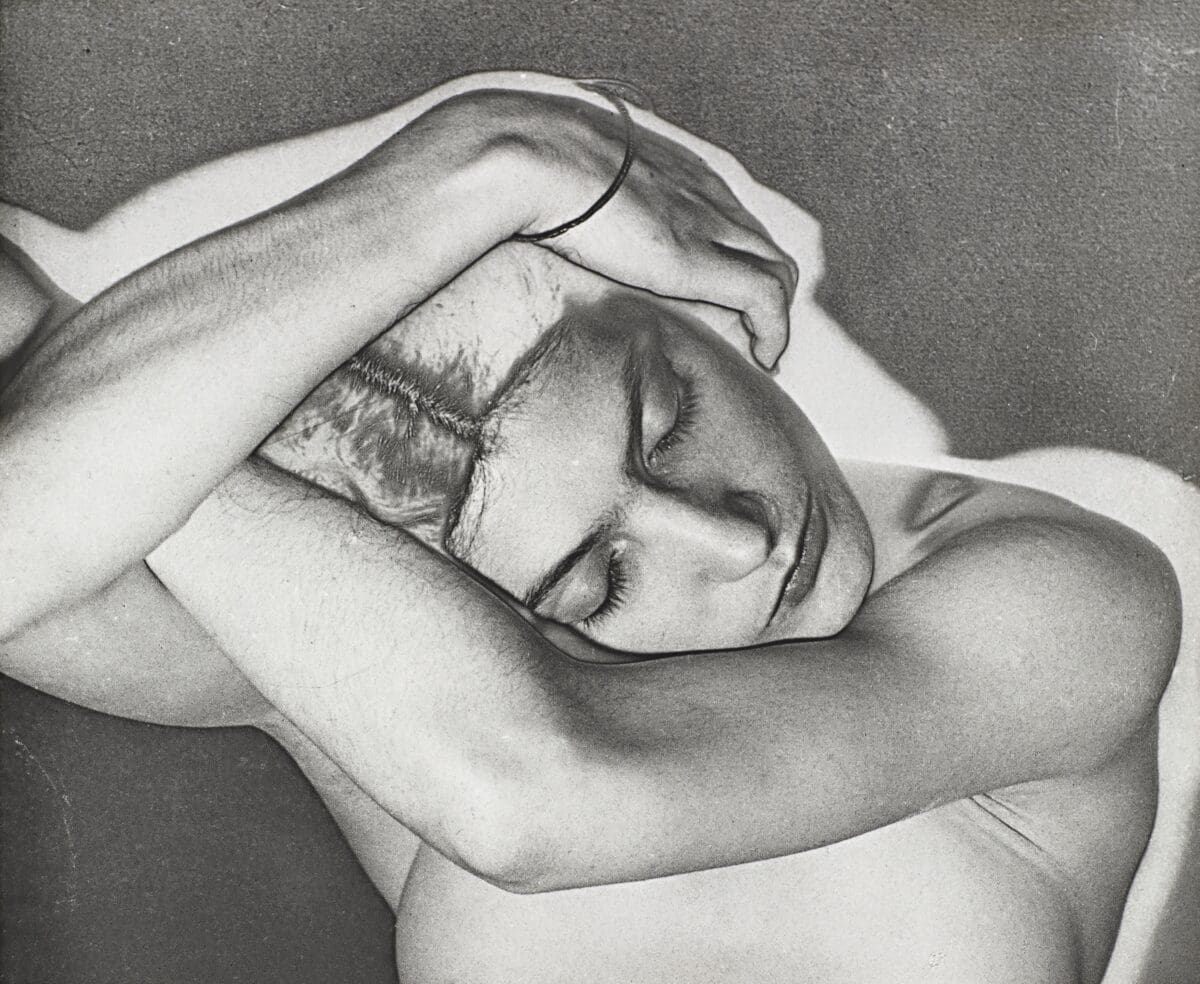

Ambitiously, Dupain opened his own Sydney studio in 1934, in his early twenties. His partner, photographer Olive Cotton, became his assistant. He began experimenting with modernist aesthetics—sunlight, abstraction, negative space, dynamic composition—a one-way conversation with distant artists like Man Ray.

In staging Man Ray and Max Dupain, Heide also includes works by Lee Miller— Man Ray’s collaborator, muse and partner—and by Olive Cotton.

“It’s important these women and their contributions aren’t forgotten,” says Harding. “Man Ray and Lee Miller elevated each other, and the same is true of Olive and Max.”

The exhibition foregrounds Dupain’s work from the 1930s, including his most famous image, The Sunbaker (1937), shot while camping with friends on the New South Wales coast. It also highlights his experiments with portraiture, techniques such as solarisation and camera-less photography known as photograms — a process Man Ray had revived and rechristened ‘rayographs’.

The Second World War shifted Dupain’s output towards documentary imagery as he responded to the conflict and his postings in the Northern Territory and Papua New Guinea. His later move away from Surrealism revealed a maturing artist more concerned with Australian life, architectural form and modernist clarity. He went on to build a successful career in commercial, architectural and documentary photography—even working for brands like David Jones.

“There aren’t a lot of comparable photographers to Dupain,” Harding says. “Olive Cotton is one, but no one else has gone to the lengths he did in what was essentially a dialogue with international modernist photographers.”

In this bold pairing, Heide reminds us that modern photography’s pulse didn’t beat only in Europe’s capitals. From Sydney’s Bond Street to Montparnasse in Paris, Dupain and Man Ray each broke boundaries, reimagining what the photograph could be. Perhaps Dupain said it best: it all came down to kicking convention “right up the arse”.

Man Ray and Max Dupain

Heide Museum of Modern Art

On now until November 9