In his solo exhibition Invisible Border Khadim Ali draws attention to those imaginary delineations that separate us. As he points out, there are the arbitrary marks on a map that portion off one country from another, and “There’s an invisible border between me and someone else.” But in the context of this exhibition, Ali’s most extensive to date, the border that the Sydney-based artist really highlights is the insidious line between ‘us’ and ‘them.’

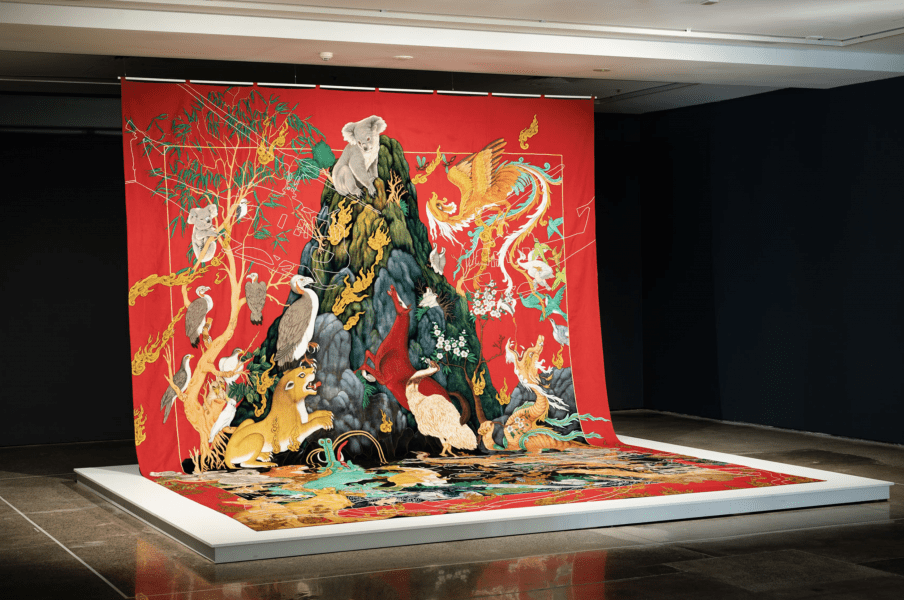

Invisible Border, at the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane (IMA), includes several massive embroidered textile pieces and the gallery website notes that “Ali’s interest in tapestries developed soon after his parents’ home in Quetta, Pakistan was destroyed by suicide bombers. Amongst the rubble and debris left from the blast, a collection of rugs and weavings remained the only thing intact…”

The matter of fact way that this information is presented throws a particular invisible border – the line between those who experience this kind of horrific event as part of daily life and those who will only ever witness such acts of violence as news from elsewhere – into startling sharp relief.

Ali’s parents survived this terrorist attack and came to Australia as critically-injured refugees. Here they were clearly marked as ‘other,’ but even in Pakistan (where Ali and his father before him were born) they suffered the ramifications of invisible borders. As Hazaras, a Persian-speaking people from Afghanistan, they were targeted, persecuted and eventually bombed.

Explosives are a particularly brutal way of wiping out a minority group, but in Invisible Border, Ali also references textile techniques to draw attention to more subtle methods of obliterating a culture. In his wall-based sound sculpture, Urbicide 2, 2020, made in collaboration with Sher Ali, he explains that the golden lines traced on the gallery wall mimic both circuitry and embroidery. The artist says that while the gold wire stands in for the copper wire of suicide vests, a deadly fashion statement that is a symbol of honour and status to many, it also harks back to intricate and colourful Afghani embroidery traditions which use golden threads.

“But now people are adapting their dress to the Saudi or the fundamentalist style,” Ali explains. “Their daily outfits are repelling the traditional way of embroidering; getting very flat. They are either wearing white or black. The white is very much coming from the Arab culture and the black is coming from ISIS culture. It’s big. They have lost their own traditions, crafts, their own culture, in this war.”

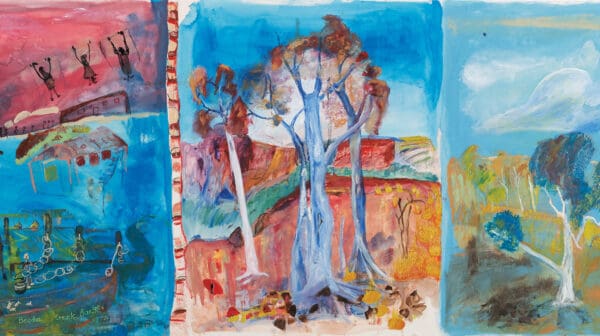

If war seems a distant problem here in ‘the lucky county’ – something that ‘they’ have to deal with, not ‘us’ – Ali’s use of imagery from the catastrophic bushfire season of 2019-2020 is a reminder that in fact no one is entirely immune from devastation and loss. Drawing on the scenes of towering walls of flame and animals literally running for their lives which dominated the media during that horribly hot summer, in his Sermon on the Mount series (which includes both mixed media textile pieces and paintings) Ali pictures koalas, kangaroos and emus as desperate refugees fleeing the cataclysm of war.

For many Australians the fallout from natural disasters is the closest we will come to first-hand experience of the all-encompassing losses visited on those caught in the crossfire of war. In addition to its overwhelming power to destroy, fire is known for its regenerative potential. Looking at Ali’s work it is possible to believe, if only for a moment, that the legacy of that terrible summer might be a growing sense of empathy for others and a weakening of the invisible borders that divide us.

Invisible Border

Khadim Ali

Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane

10 April – 5 June

UNSW Galleries, Sydney

20 Aug – 20 Nov