Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

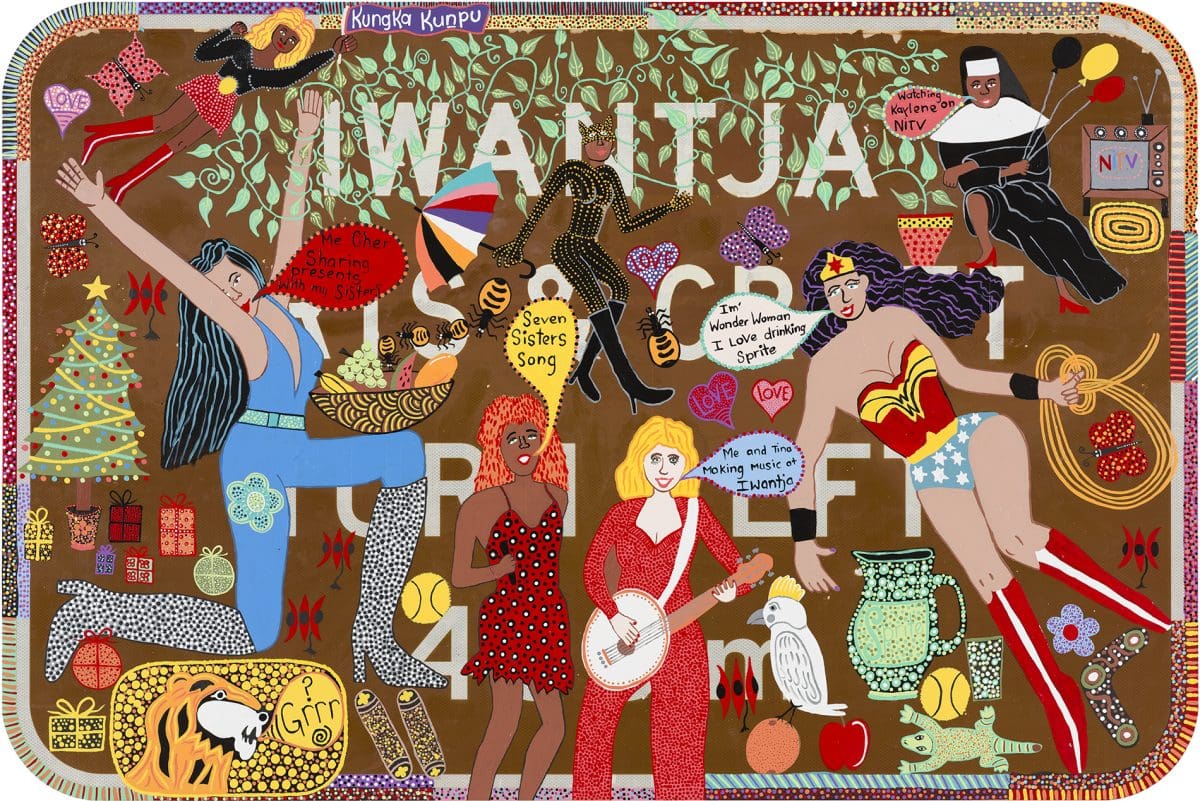

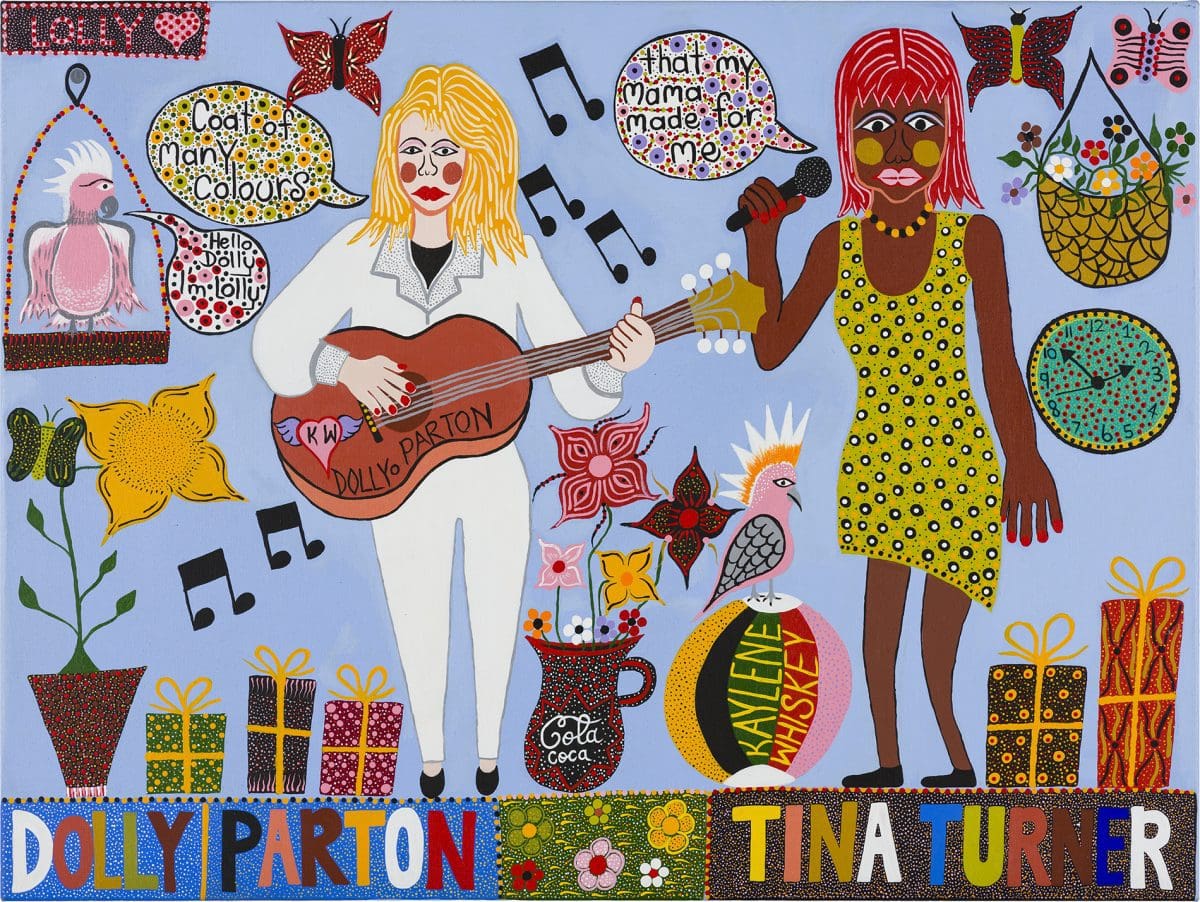

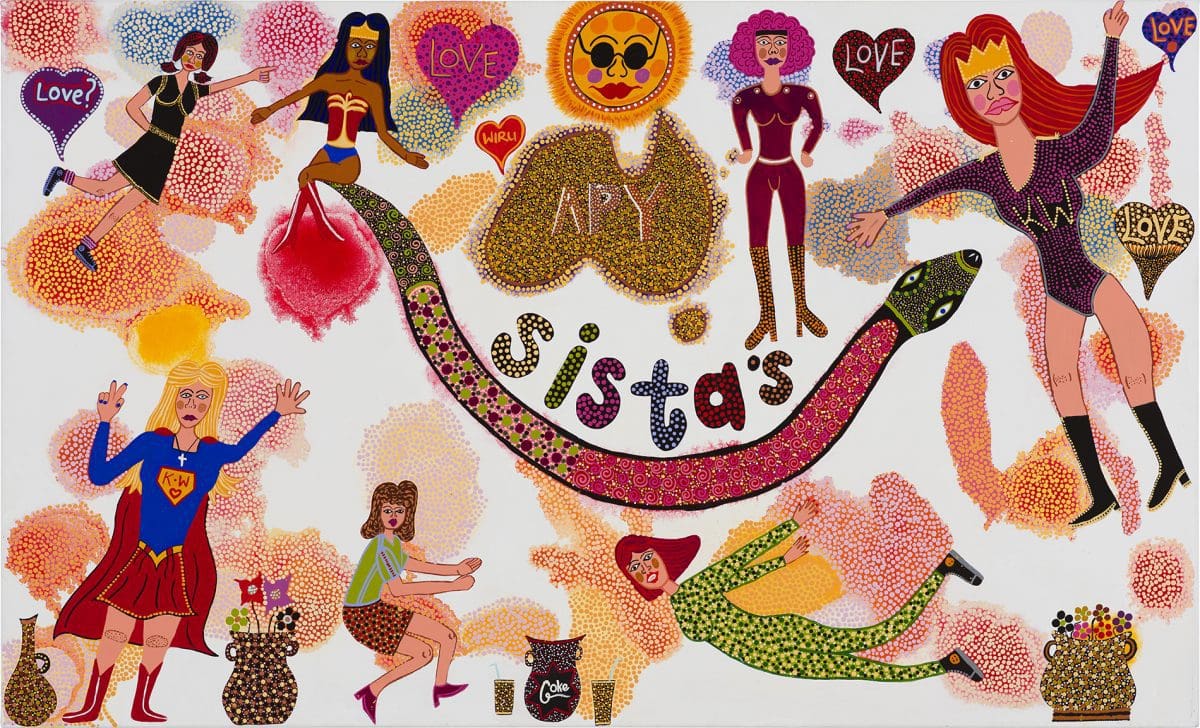

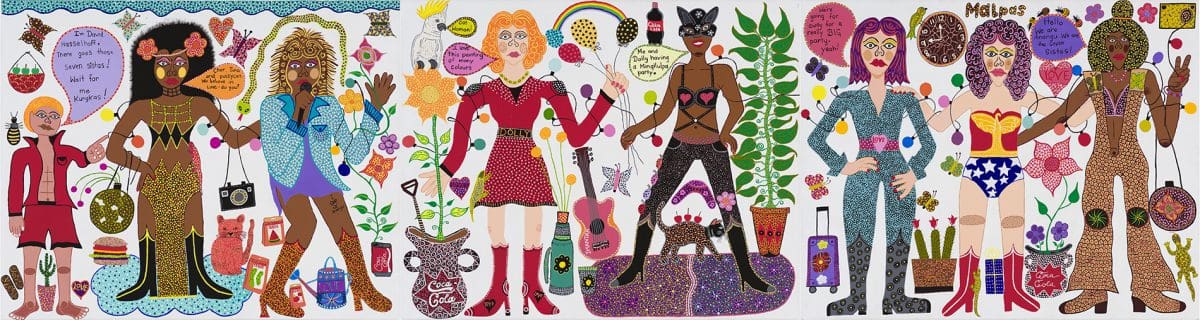

An effervescent burst of celebrities and pop iconography flourish in Kaylene Whiskey’s paintings. Her exuberant love of famous subjects, which include Dolly Parton, Cher, David Bowie, Tina Turner, Michael Jackson, Wonder Woman and President Obama, are vividly expressed in distinct comic book style. A unique talent for capturing mainstream culture’s most recognisable personalities is turning the Pitjantjatjara artist from the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands of South Australia into a celebrity of her own making.

With flair and vibrancy, Whiskey’s multicoloured canvases bring a Pop Art aesthetic to the Yankunytjatjara, Southern Desert region. The self-taught artist developed her practice through Iwantja Arts, an art centre in the Indulkana Community, and her acclaim is growing. Having won the 2018 Sir John Sulman Prize, the 2019 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award for ‘General Painting’, and being an Archibald Prize finalist, Whiskey’s work is redefining contemporary First Nations art.

Born in 1976, the artist’s large-scale paintings embody her generation’s experience of growing up with MTV and the ubiquity of consumer brands like Coca Cola and KFC. She acknowledges that these experiences have shaped who she is, as well as forming the very desires of her generation—but this is without severing contemporaneous expression as part of the oldest living Indigenous culture in the world.

Whiskey’s work is celebratory. In Dolly visits Indulkana, a 2020 Archibald finalist work, Whiskey illustrates the iconic country music singer visiting Whiskey’s community: Parton is welcomed with exuberant spirit as Wonder Woman flies in the background and Diet Coke is served in a ceramic vase, which is placed next to a boomerang decorated in desert motifs and colours. In an interview with the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Whiskey described how “It’s one of my dreams for Dolly to come and visit me in Indulkana. I love to listen to her music while I paint: ‘9 to 5’, ‘Coat of many colours’, ‘Jolene’, and my number one, ‘Islands in the stream’ with Kenny Rogers. I often think, ‘If Dolly came to visit, what would she do? What would she say? And what would she be wearing?’”

Whiskey’s vision comes from a place of vast imagining rather than a story of cultural loss or environmental destruction. We are shown what happens when two opposing social systems—Aboriginal Australia and Western pop culture—collide and strangers from across the globe meet. When Parton does meet Indulkana, the viewer is shown a scene of mutual admiration where the two women’s differences and similarities as storytellers incite an exchange, which is playful but equally respectful towards the vastly different cultures that they come from. As Whiskey further described in her interview: “I had a lot of fun bringing Dolly to Indulkana on the canvas. Once I had finished the painting I thought, ‘You know what? Dolly needs more sparkles’, so I added the plastic jewels as the finishing touch!” While the indelible impact of Western colonial capitalism on First Nations people is vast, Whiskey offers respite illustrating that within the destruction she and others have lived through, one can still find joy in the music and sparkle of international pop icons.

This playfulness is also evident when David Bowie casually drops by in Super Anangu, 2018. In a painting which oozes fun and pleasure, Bowie proclaims “Let’s Dance!” to both Kaylene and Michael Jackson. And the work also provides insight into Whiskey’s sense of place where an evident love and connection to her desert landscape abounds—even if her glossy subject matter suggests otherwise. In the catalogue essay for the 2018 iteration of The National: New Australian Art, Daniel Mudie Cunningham writes how “casting her cherished superstars within comic book– like canvases, Whiskey merges fanciful pop narratives with her own personal experience and daily life in Indulkana.” As he suggests, Whiskey walks in multiple worlds with humour and reverence, and refuses to allow globalised pop culture, where buckets of KFC litter the landscape, to dilute her sovereignty.

Currently, Whiskey is a highly sought after artist. Her work is exhibiting for the 2021 Tarnanthi Festival (showing until late January 2022), and in February this year Whiskey will present a single-channel video work for Melbourne Art Fair, which is an awarded commission. Maree Di Pasquale, CEO and fair director, has described the significance of Whiskey’s inclusion: “A female Australian artist on the rise, Kaylene’s work deeply aligns with the fair’s theme Djeembana/Place, where she explores her connection as an Indigenous Australian to Indulkana, her hometown, as well as her Yankunytjatjara heritage.”

In addition, a recent collaboration with fashion label WAH-WAH has increased Whiskey’s celebrity status, while also asserting the Blak matriarch into wider public consciousness. WAH-WAH’s Kaylene Whiskey knitted jumper, which features the artist’s iconic imagery such as Wonder Woman, has exploded on Instagram as the next generation of First Nation stars wear the garment in their posts. This includes the likes of Carly Sheppard, Jazz Money, This Mob and Māori filmmaker turned Hollywood legend, Taika Waititi.

While this step into fashion reflects an increasing appetite for First Nations culture, it also feels like an obvious extension of Whiskey’s practice. Refusing containment in the gallery, Whiskey has spread across social media, not unlike the personalities within the MTV world she grew up in. Her vitality and cross-cultural influence, which moves between high art and the mainstream, is a force which continues to evolve with wondrous joy.

Tarnanthi 2021

Group exhibition

Art Gallery of South Australia

Until 30 January

Melbourne Art Fair: Kaylene Whiskey Commission

Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre, South Wharf, Victoria

17 February–20 February

This article was originally published in the January/February 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.